Besides the above gods are mentioned the

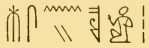

“angel (or messenger) of the two gods,”(Unȧs 408);

and the

“Āshem that dwelleth within Ȧru,”(Tetȧ 351).

Allusions are made to the following important stars :—

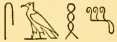

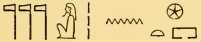

| Nekhekh (Tetȧ 218), |  |

| Sepṭet (Tetȧ 349), |  , i.e., the Dog Star. , i.e., the Dog Star. |

| Saḥ (Tetȧ 349), |  , i.e., Orion. , i.e., Orion. |

| Seḥuṭ (Pepi II. 857), |  . . |

The Pyramid Texts show that in addition to the gods already enumerated there existed certain classes of beings to whom were attributed the nature of the gods, e.g.:—

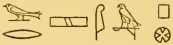

| The Āfu (Pepi 11. 951), |  • • |

| The Utennu (Pepi II. 951), |  . . |

| The Urshu of Pe (Pepi II. 849), |  . . |

| The Urshu of Nekhen (Pepi II. 849), |  . . |

| The Ḥenmemet (Unȧs 211), |  . . |

| The Set beings, superior and inferior, (Pepi II. 951), |  . . |

| The Shemsu Ḥeru (Pepi I. 166), |  . . |

Of the functions of the Āfu and Utennu nothing whatever is known. The urshu, i.e., the Watchers, of Pe and Nekhen may have been groups of well-known gods, who were supposed to “watch over” and specially protect these cities ; but, on the other hand, they may only have been the messengers, or angels, of the souls of Pe and Nekhen. The Ḥenmemet beings are likewise a class of divine beings about whom we have no exact information.

In certain texts they are mentioned in connection with gods and men in such a manner that they are supposed to represent “unborn generations,” but this rendering will not suit many of the passages in which the word occurs, and in those in which it seems to do so many other hypothetical meanings would fit the context just as well. The passage in which the Set beings are referred to must belong to the period when the god Set was regarded as a beneficent being and a god who was, with Horus, a friend and helper of the dead.

The text quoted above shows that, like Horus, Set was supposed to be the head of a company of divine beings with attributes and characteristics similar to those of himself, and that this company was divided into two classes, the upper and the lower, or perhaps even the celestial and the terrestrial.

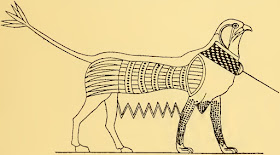

Last must be mentioned the Shemsu Heru, or the “Followers of Horus,” to whom many references are made in funeral literature; their primary duties were to minister to the god Horus, son of Isis, but they were also supposed to help him in the performance of the duties which he undertook for the benefit of the dead. In the religious literature of the Early Empire they occupy the place of the “Mesniu,” , of Horus of Beḥuṭet, the modern Edfû, i.e., the workers in metal, or blacksmiths, who are supposed to have accompanied this god into Egypt, and to have assisted him by their weapons in establishing his supremacy at Beḥuṭet, or Edfû. The exploits of this god will be described later on in the section treating of Horus generally.

, of Horus of Beḥuṭet, the modern Edfû, i.e., the workers in metal, or blacksmiths, who are supposed to have accompanied this god into Egypt, and to have assisted him by their weapons in establishing his supremacy at Beḥuṭet, or Edfû. The exploits of this god will be described later on in the section treating of Horus generally.

, of Horus of Beḥuṭet, the modern Edfû, i.e., the workers in metal, or blacksmiths, who are supposed to have accompanied this god into Egypt, and to have assisted him by their weapons in establishing his supremacy at Beḥuṭet, or Edfû. The exploits of this god will be described later on in the section treating of Horus generally.

, of Horus of Beḥuṭet, the modern Edfû, i.e., the workers in metal, or blacksmiths, who are supposed to have accompanied this god into Egypt, and to have assisted him by their weapons in establishing his supremacy at Beḥuṭet, or Edfû. The exploits of this god will be described later on in the section treating of Horus generally.The God Of Four Faces

In the text of Pepi I. (line 419) we have a reference to a god with four faces in the following words:—

“Homage to thee, O thou who hast four faces which rest and look in turn upon what is in Kenset, and who bringest storm . . . . . ! Grant thou unto this Pepi thy two fingers which thou hast given to the goddess Nefert, the daughter of the great god, as messenger[s] from heaven to earth when the gods make their appearance in heaven.Thou art endowed with a soul, and thou dost rise [like the sun] in thy boat of seven hundred and seventy cubits.Thou hast carried in thy boat the gods of Pe, and thou hast made content the gods of the East. Carry thou this Pepi with thee in the cabin of thy boat, for this Pepi is the son of the Scarab which is born in Ḥetepet beneath the hair of the city of Iusāas the northern, and he is the offspring of Seb.It is he who was between the legs of Khent-maati on the night wherein he guarded (?) bread, and on the night wherein he fashioned the heads of arrows.Thou hast taken thy spear which is dear to thee, thy pointed weapon which thrusteth down river banks, with a double point like the darts of Rā, and a double haft like the claws of the goddess Mafṭet.”

Companies Of The Gods

Throughout the Pyramid Texts frequent mention is made of one group, or of two or three groups, of nine gods.

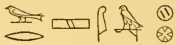

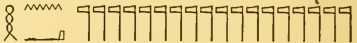

Thus in Unȧs (line 179) we read of

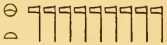

“bowing low to the ground before the nine gods,”;

and in line 234 we are told that the king’s bread consists of

“the word of Seb which cometh forth from the mouth of the nine male gods,”

.

The god Seshaȧ, , is said in line 382 to have been “begotten by Seb and brought forth by the nine gods,”

, is said in line 382 to have been “begotten by Seb and brought forth by the nine gods,”

, is said in line 382 to have been “begotten by Seb and brought forth by the nine gods,”

, is said in line 382 to have been “begotten by Seb and brought forth by the nine gods,”;

and in line 592 Rā is said to be the “chief of the nine gods,”

.

From several passages (e.g., Unȧs 251) we learn that one company of nine gods was called the “Great,”

,

and that another company was called the “Little,”

,

and the “nine gods of Horus” are spoken of side by side with “the gods,”

(line 443),

but whether this group is to be connected with the Great or Little company of gods cannot be said.

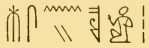

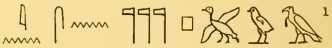

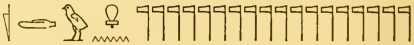

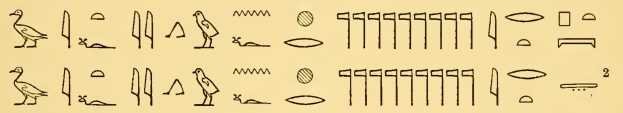

A double group of nine gods is frequently referred to, e.g., in Tetȧ, line 67, where it is said, “The eighteen gods cense Tetȧ, and his mouth is pure,”

;

and in Pepi I., line 273, where we read that the “two lips of Meri-Rā are the eighteen gods,”

;

and again in line 407, where Pepi I. is said to be “with the eighteen gods in Qebhu,” and to be the“fashioner of the eighteen gods,”

We may perhaps assume that the eighteen gods include the Great and the Little companies of the gods, but, on the other hand, as “male and female gods” are mentioned in the text of Tetȧ, nine of the eighteen gods may be feminine counterparts of the other nine, who must therefore be held to be masculine.

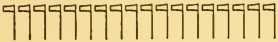

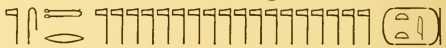

But the texts of Tetȧ (line 307) and Pepi I. (line 218) show that there was a third company of nine gods recognized by the priests of Heliopolis, and we find all three companies represented thus:

Paut Or Substance Of The Gods

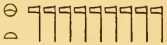

The Egyptian word here rendered “company” is pauti or paut, which may be written either or

or , and the meaning usually attached to it has been “nine.”

, and the meaning usually attached to it has been “nine.”

or

or , and the meaning usually attached to it has been “nine.”

, and the meaning usually attached to it has been “nine.”

It is found in texts subsequent to the period of the pyramids at Ṣaḳḳâra thus written:—

paut neteru, “paut of the gods”;

the double company of the gods is expressed by

pautti,

or we may have

, paut neteru aāt paut neteru netcheset,

i.e., “the (Great company of gods and the Little company of the gods.”

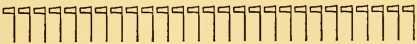

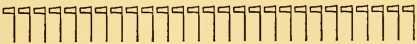

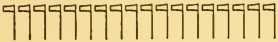

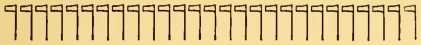

The fact that a company of gods is represented by nine axes, , has led to the common belief that a company of the gods contained nine gods, and for this reason the word paut has been explained to mean “nine.”

, has led to the common belief that a company of the gods contained nine gods, and for this reason the word paut has been explained to mean “nine.”

, has led to the common belief that a company of the gods contained nine gods, and for this reason the word paut has been explained to mean “nine.”

, has led to the common belief that a company of the gods contained nine gods, and for this reason the word paut has been explained to mean “nine.”

It is quite true that the Egyptians frequently assigned nine gods to the paut, as we may see from such passages as Unȧs 235, and especially from line 283, where it is said,

“Grant thou that this Unȧs may rule the nine, and that he may complete the company of the gods,”.

But the last quoted passage proves that a paut of the gods might contain more than nine divine beings, for it is clear that if the intent of the prayer was carried out the paut referred to in it would contain ten, king Unȧs being added to the nine gods.

Again, in a litany to the gods of the Great company given in the Unȧs text (line 240 ff.) we see that the paut contains

- Tem,

- Shu,

- Tefnut,

- Seb,

- Nut,

- Isis,

- Set,

- Nephthys,

- Thoth,

- and Horus,

i.e., ten gods, without counting the deceased, who wished to be added to the number of the gods.

In the text of Mer-en-Rā (line 205) the paut contains nine gods, and it is described as the “Great paut which is in Ȧnnu” (Heliopolis), whilst in the text of Pepi II. (line 669) the same paut is said to contain

- Tem,

- Shu,

- Tefnut,

- Seb,

- Nut,

- Osiris,

- Osiris-Khent-Ȧmenti,

- Set,

- Horus,

- Rā,

- Khent-maati,

- and Uatchet,

i.e., twelve gods.

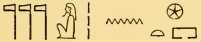

Similarly the gods of the Little paut are more than nine in number, and in Unȧs (line 253 f.) they are thus enumerated :—

- Rāt,

,

, - the dweller in Ȧnnu,

,

, - the dweller in Āntchet,

,

, - the dweller in Het-Serqet,

,

, - the dweller in the divine palace,

,

, - the dweller in etch-paār,

,

, - the dweller in Orion,

,

, - the dweller in Ṭep,

,

, - the dweller in Ḥet-ur-ka,

,

, - the dweller in Unnu of the South,

,

, - the dweller in Unnu of the North,

.

.

Thus the Little paut contained eleven gods, not counting the deceased who desired to be added to their number. The fact that the paut contained at times more than nine gods is thus explained by M. Maspero

“The number nine was the original number, but each of the nine gods, especially the first and the last, could be developed.”

Thus if it was desired to add the god Amen of the Theban triad to the paut of Heliopolis, he could be set at the head of it either in the place of Temu, the legitimate chief of the paut, or side by side with him. Mut, the consort of Amen, might be included in the paut, but Ȧmen and Mut would together only count as one god. Similarly, any one or all of the gods who belonged to the shrine of Amen could be included with that god himself in the paut of Heliopolis, and yet the number of that paut was supposed to be increased only by one.

In other words, the admission of one god into a paut brought with it the admission of all the gods who were in any way connected with him, but their names were never included among those of the original members of it. This explanation is very good as far as it goes, but it must not be taken as a proof that the Egyptians argued in this manner, or that they argued at all about it.

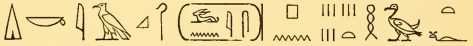

The nine axes are, beyond doubt, intended to represent nine gods, i.e., a triad of triads, but the signs

are, beyond doubt, intended to represent nine gods, i.e., a triad of triads, but the signs paut neteru, must be translated not “Neunlieit,” as Brugsch rendered them, but the “stuff of the nine gods,” i.e., the substance or matter out of which the nine gods were made. The word paut,

paut neteru, must be translated not “Neunlieit,” as Brugsch rendered them, but the “stuff of the nine gods,” i.e., the substance or matter out of which the nine gods were made. The word paut,  , means “dough cake,” or cake of bread which formed part of the offerings made to the dead; similarly paut is the name given to the plastic substance out of which the earth and the gods were formed, and later, when applied to divine beings or things, it means the aggregation or entirety of such beings or things.

, means “dough cake,” or cake of bread which formed part of the offerings made to the dead; similarly paut is the name given to the plastic substance out of which the earth and the gods were formed, and later, when applied to divine beings or things, it means the aggregation or entirety of such beings or things.

are, beyond doubt, intended to represent nine gods, i.e., a triad of triads, but the signs

are, beyond doubt, intended to represent nine gods, i.e., a triad of triads, but the signs paut neteru, must be translated not “Neunlieit,” as Brugsch rendered them, but the “stuff of the nine gods,” i.e., the substance or matter out of which the nine gods were made. The word paut,

paut neteru, must be translated not “Neunlieit,” as Brugsch rendered them, but the “stuff of the nine gods,” i.e., the substance or matter out of which the nine gods were made. The word paut,  , means “dough cake,” or cake of bread which formed part of the offerings made to the dead; similarly paut is the name given to the plastic substance out of which the earth and the gods were formed, and later, when applied to divine beings or things, it means the aggregation or entirety of such beings or things.

, means “dough cake,” or cake of bread which formed part of the offerings made to the dead; similarly paut is the name given to the plastic substance out of which the earth and the gods were formed, and later, when applied to divine beings or things, it means the aggregation or entirety of such beings or things.

Thus in the Papyrus of Ani (sheet i., line 6) the god Tatunen is declared to be

“one, the maker of mankind, and of the material of the gods of the South and the North, the West and the East.”

Substance Of The Gods

But there was a primeval matter out of which heaven was made, and also a [primeval] matter out of which the earth was made, and hence Kheperȧ, the great creator of all things, is said in Chapter xvii. (line 116) of the Book of the Dead to possess a body which is formed of both classes of matter (paut).

And again in Chapter lxxxv. (line 8) the deceased, wishing to identify himself with this divine substance, says,

“I am the eldest son of the divine pautti, that is to say, the soul of the souls of the gods of everlasting, and my body is everlasting, and my creations are eternal, and I am the lord of years, and the prince of everlastingness.”

In the words which are put into the mouth of Kheperȧ, who is made to describe his creation of the world, the god says,

“I produced myself from the [primeval] matter [which] I made,”

;

this is the only meaning which can be extracted from the Egyptian words, and the context, which the reader will find given in the section on the Creation, proves that it is the correct one. The word “primeval,” which is added in brackets, is suggested by the texts wherein paııtti is accompanied by ṭep, i.e., “first,” in point of time, compare

ṭep, i.e., “first,” in point of time, compare , “first matter,” that is to say, the earliest matter which was created, and the matter which existed before anything else. From the above facts it is clear that the meaning “Neunheit” must not be given to the Egyptian word paııt.

, “first matter,” that is to say, the earliest matter which was created, and the matter which existed before anything else. From the above facts it is clear that the meaning “Neunheit” must not be given to the Egyptian word paııt.

ṭep, i.e., “first,” in point of time, compare

ṭep, i.e., “first,” in point of time, compare , “first matter,” that is to say, the earliest matter which was created, and the matter which existed before anything else. From the above facts it is clear that the meaning “Neunheit” must not be given to the Egyptian word paııt.

, “first matter,” that is to say, the earliest matter which was created, and the matter which existed before anything else. From the above facts it is clear that the meaning “Neunheit” must not be given to the Egyptian word paııt.Three Companies Of The Gods

We have now seen that, so far back as the Vth Dynasty, the priests of Heliopolis conceived the existence of three companies of gods ; the first two they distinguished by the appellations “Great” and “Little,” but to the third they gave no name.

The gods of the first or “Great” company are well known, and their names are :—

- Tem, the form of the Sun-god which was worshipped at Heliopolis.

- Shu.

- Tefnut.

- Seb.

- Nut.

- Osiris.

- Isis.

- Set.

- Nephthys.

Sometimes this company is formed by the addition of Horus and the omission of Tem.

The names of gods of the second or “Little” company appear to be given in the text of Unȧs, line 253 ff., where we have enumerated :—

- Rāt.

- Ȧm-Ȧnnu.

- Ȧm-Āntchet.

- Ȧm-Ḥet-Ṣerqet-ka-ḥetepet.

- Ȧm-Neter-ḥet.

- Ȧm-Ḥetch-paār.

- Ȧm-Saḥ.

- Ȧm-Ṭep.

- Ȧm-Ḥet-ur-Rā.

- Ȧm-Unnu-resu.

- Ȧm-Unnu-meḥt.

It must, however, be noted that whereas in the text the address to the Great company of the gods as a whole follows the separate addresses to each, the address to the Little company precedes the separate addresses to each ; still there is no reason for doubting that the second group of names given above are really those of the Little company of the gods.

The names of the gods of the third company are unknown, and the texts are silent as to the functions which the company was supposed to perform ; the Great and Little companies of the gods are frequently referred to in texts of all periods, but the third company is rarely mentioned.

Thus in the text of Pepi I. (line 43),

the king is said to sit on an iron throne and to weigh words at the head of the Great company of gods in Ȧnnu;

the two companies of the gods lift up the head of Pepi (line 97),

and he takes the crown in the presence of the Great company (line 117);

he sits at the head of the two companies (line 167),

and in their boat (line 169);

and he stands between the two companies (line 186).

the king is said to sit on an iron throne and to weigh words at the head of the Great company of gods in Ȧnnu;

the two companies of the gods lift up the head of Pepi (line 97),

and he takes the crown in the presence of the Great company (line 117);

he sits at the head of the two companies (line 167),

and in their boat (line 169);

and he stands between the two companies (line 186).

It has already been suggested that the Great company of gods was a macrocosm of a primitive kind, and the Little company a microcosm; this view is very probably correct, and is supported by passages like the following :—

“The son of his father is come with the company of the gods of heaven, . . . the son of his father is come with the company of the gods of earth.”

From numerous passages in texts of all periods it is clear that the Egyptians believed that heaven was in many respects a duplicate of earth, and, as it was supposed to contain a celestial Nile, and sacred cities which were counterparts of those on the earth and which were called by similar names, it is only reasonable to assign to it a company of gods who were the counterparts of those on earth. And as there were gods of heaven and gods of earth, so also were there gods of the Ṭuat, or Underworld, who were either called ṭuat, , or, or neteru en ṭuat,

, or, or neteru en ṭuat, .

.

, or, or neteru en ṭuat,

, or, or neteru en ṭuat, .

.

This being so, we may assume that when the writers of the Pyramid Texts mentioned three companies of the gods,  , they referred to the company of the gods of heaven, the company of the gods of earth, and the company of the gods of the Underworld, meaning thereby what the writer of the XXIIIrd Chapter of the Book of the Dead meant when he spoke of

, they referred to the company of the gods of heaven, the company of the gods of earth, and the company of the gods of the Underworld, meaning thereby what the writer of the XXIIIrd Chapter of the Book of the Dead meant when he spoke of

, they referred to the company of the gods of heaven, the company of the gods of earth, and the company of the gods of the Underworld, meaning thereby what the writer of the XXIIIrd Chapter of the Book of the Dead meant when he spoke of

, they referred to the company of the gods of heaven, the company of the gods of earth, and the company of the gods of the Underworld, meaning thereby what the writer of the XXIIIrd Chapter of the Book of the Dead meant when he spoke of“the company of all the gods,”.

In the Pyramid Texts, however, and in the later Recensions of the Book of the Dead which are based upon them, the pautti neteru,  , or

, or  , were intended to represent the Great and Little companies of the gods, and these only ; the members of each company varied in different cities and in different periods, but the principle of such variation is comparatively simple. Long before the priests of Heliopolis grouped the gods of Egypt into companies certain very ancient cities had their own special gods whom they probably inherited from their predecessors, i.e., the predynastic Egyptians.

, were intended to represent the Great and Little companies of the gods, and these only ; the members of each company varied in different cities and in different periods, but the principle of such variation is comparatively simple. Long before the priests of Heliopolis grouped the gods of Egypt into companies certain very ancient cities had their own special gods whom they probably inherited from their predecessors, i.e., the predynastic Egyptians.

, or

, or  , were intended to represent the Great and Little companies of the gods, and these only ; the members of each company varied in different cities and in different periods, but the principle of such variation is comparatively simple. Long before the priests of Heliopolis grouped the gods of Egypt into companies certain very ancient cities had their own special gods whom they probably inherited from their predecessors, i.e., the predynastic Egyptians.

, were intended to represent the Great and Little companies of the gods, and these only ; the members of each company varied in different cities and in different periods, but the principle of such variation is comparatively simple. Long before the priests of Heliopolis grouped the gods of Egypt into companies certain very ancient cities had their own special gods whom they probably inherited from their predecessors, i.e., the predynastic Egyptians.

Thus the goddess of Saïs was Nit, or Net, or Neith ;

the goddess of Per-Uatchet was Uatchet;

the goddess of Dendera was Hathor;

the goddess of Nekheb was Nekhebet;

the god of Edfû was Horus;

the god of Heliopolis was Tem;

and so on.

the goddess of Per-Uatchet was Uatchet;

the goddess of Dendera was Hathor;

the goddess of Nekheb was Nekhebet;

the god of Edfû was Horus;

the god of Heliopolis was Tem;

and so on.

When the priests of these and other cities found that, for some reason, they were obliged to accept the theological system formulated by the priests of Heliopolis and its Great company of gods, they did so readily enough, but they always made the great local god or goddess the head or chief, , of the company.

, of the company.

, of the company.

, of the company.The Companies Of The Gods

At Heliopolis, where the chief local god was called Tem, the priests joined their god to Rā, and addressed many of their prayers and hymns to Tem-Rā or Rā-Tem. At Edfû the great local god Horus of Beḥuṭet was either made to take the place of Tem, or was added to the Heliopolitan company in one form or another.

The same thing happened in the case of goddesses like Neith, Uatchet, Nekhebet, Hathor, etc. It was found to be hopeless to attempt to substitute the Heliopolitan company of gods for Neith in the city of Saïs, because there the worship of that goddess was extremely ancient and was very important.

The fact that her name forms a component part of royal names very early in the 1st Dynasty proves that her worship dates from the first half of the archaic period, and that it is much older than the theological system of Heliopolis. But when the priests of Saïs adopted that system they associated her with the head of the company of the gods, and gave her suitable titles and ascribed to her proper attributes, in accordance with her sex, which would make her a feminine counterpart to the god Tem.

The god Tem was the Father-god, and the lord of heaven, and the begetter of the gods, therefore Neith became

“the great lady, the mother-goddess, the lady of heaven, and queen of the gods,”·

Elsewhere she is called

“mother of the gods,”

and just as Tem was declared to have been self-produced, so we find the same attribute ascribed to Neith, and she is said to be

“the great lady, who gave birth to Rā, who brought forth in primeval time herself, never having been created,”.

The same thing happened at the cities of Per-Uatchet in the Delta and Nekhebet in Upper Egypt, for at one place Uatchet, the ancient and local goddess, became the head of the company of gods, and the goddess Nekhebet at the other.

It is interesting to note that the priests of Heliopolis themselves included Uatchet in their Great company of the gods, as we may see from the text of Pepi II., where we find that the deceased king prays concerning the welfare of his pyramid “to the great paut of gods in Ȧnnu,” i.e.,

- Tem,

- Shu,

- Tefnut,

- Seb,

- Nut,

- Osiris,

- Set,

- Nephthys,

- Khent-Maati,

- and Uatchet.

The goddess Hathor at Dendera was treated by the priests there as was Neith at Saïs, for every conceivable attribute was ascribed to her, and her devotees declared that she was the mother of the gods, and the creator of the heavens and the earth, and of everything which is in them. In fact, both Neith and Hathor were made to assume all the powers of the god Tem, and indeed of every solar god.

Local Gods

The general evidence derived from a study of texts of all periods shows that the chief local gods of many cities never lost their exalted positions in the minds of the inhabitants, who clung to their belief in them with a consistency and conservatism which are truly Egyptian. In fact, the god of a nome, or the god of the capital city of a nome, when once firmly established, seems to have maintained his influence in all periods of Egyptian history, and though his shrine may have fallen into oblivion as the result of wars or invasions, and his worship have been suspended from time to time, the people of his city always took the earliest opportunity of rebuilding his sanctuary and establishing his priests as soon as prosperity returned to the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment