Qebhet (also known as Kebehwet, Kabechet or Kebechet) is a benevolent goddess of ancient Egypt. She is the daughter of the god of death, Anubis, granddaughter of the goddess Nephthys and god Osiris. She is the personification of cool, refreshing water and is mentioned frequently in the Egyptian Book of the Dead as she brings water to the souls of the dead in the Hall of Truth as they stand awaiting judgment by Osiris and the Forty-Two Judges.

UNKNOWN ORIGINS

She was originally a serpent deity, known as "the celestial serpent" in the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE) but was re-imagined as a goddess associated with the land of the dead, daughter of Anubis and "the king's sister", though who the `king' is remains unclear. Anubis was conceived from an affair between Nephthys (who was married to Set) and Osiris (married to Isis). Nephthys was drawn to the beauty of Osiris and transformed herself into an image of Isis, tricking Osiris into sleeping with her.

As Nephthys and Osiris were brother and sister is is possible that this story became mirrored in the conception of Qebhet. Anubis was an ancient god and judge of the dead before Osiris rose in popularity and replaced him. Possibly the story of Qebhet formed an earlier tale involving Anubis in the role of Osiris and some other goddess in the part of Nephthys. Osiris was considered the "first king" and often references to "the king" indicate this god but, in this case, it does not seem to make sense. Qebhet is never linked to Osiris as a daughter and the reference to "the king's sister" remains a mystery.

QEBHET'S SERVICE TO THE DEAD

The Egyptians believed that the afterlife was a mirror image of life on earth in Egypt. One of the reasons Egyptians preferred not to campaign far from their land was the concern in dying and being buried somewhere beyond the boundaries of their native land and so not being able to pass on to the Hall of Truth and, from there, to the Field of Reeds. If someone died in Egypt, however great or humble, they were buried in the earth of their mother and so passed on to the afterlife with relative ease.

This same paradigm held for all other aspects of the soul. Since they held that the immortal soul had all the needs and desires it did in the body, it might well become thirsty standing in line in the Hall of Truth, and Qebhet would have attended to this need. Although it does not seem she ever had a large cult following, she may have played a part or made some kind of appearance in religious events such as the Festival of the Wadi which was a celebration of the lives of the dead and of the living. The Egyptologist Lynn Meskell writes:

Religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations. They acted in a multiplicity of related spheres. There were festivals of the gods, of the king, and of the dead...The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi was a key example of a festival of the dead, which took place between the harvest and the Nile flood. In it, the divine boat of Amun traveled from the Karnak temple to the necropolis of Western Thebes. A large procession followed, and living and dead were thought to commune near the graves which became houses of the joy of the heart on that occasion. (Nardo, 100).

QEBHET PLAYED AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE RITUALS OF DEATH IN THAT SHE ASSURED THE STILL-LIVING THAT THEIR LOVED ONE WAS CARED FOR.

One of the most important aspects in honoring the dead in ancient Egypt (as well as Greeceand elsewhere) was their remembrance and no one wished to think of their departed loved one thirsting while awaiting trial before the great god Osiris in the afterlife. Qebhet, therefore, played an important role in the rituals of death in that she assured the still-living that their loved one was cared for and, furthermore, that they themselves would also be when it came their own time to stand in the hall of judgement. Further, the ritual cleansing of the body of the corpse by clean water was a vital element in the burial of the dead and Qebhet symbolized this purification.

She was also thought to play an especially vital role in the revival of the soul after death. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson writes how Qebhet personally tended the soul of the dead king and "refreshed and purified the heart of the deceased monarch with pure water from four nemset jars [ritual funerary vessels] and that the goddess helped open the `windows of the sky' to assist the king's resurrection" (223). To `open the windows of the sky' meant to liberate the soul from the body and Qebhet seems to have come to perform this service for all the dead, not just the royalty. Her grandmother, Nephthys, was known as "Friend of the Dead" and Qebhet came to be associated with this same kind of care and concern for the departed souls.

ASSOCIATION WITH HARMONY AND BALANCE

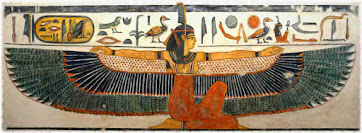

Qebhet is often pictured as a serpent or an ostrich bringing water. She was never worshipped to the degree of Isis or Hathor - or even much lesser deities - but was revered and respected and, at certain times, became associated with the Nile and cults which grew up in worship of the river. This is hardly surprising as she was always closely associated with pure, clean water. As the Nile was associated with Milky Way and the courses of the gods, Qebhet also became linked with the sky in both daylight and darkness. In her role as a purifier, she would also have been linked with the concept of Ma'at, eternal harmony and truth, which was the central guiding principle in ancient Egyptian culture.

Her earlier image as a celestial serpent was probably never completely forgotten even after she was imagined in human form in the land of the dead. Qebhet's association with the Milky Way and the divine Nile probably come from this early understanding of the goddess. The earthly plane of existence was thought to be a reflection of the eternal realm of the gods and so balance was struck through Qebhet as a goddess of the ever-changing night sky and also of the river of life which flowed through the Nile Valley to the sea. Her place among the dead would have further illustrated the Egyptian value of harmony in that a celestial goddess would humble herself to provide water to the souls of mortals. She would then have been a role model for the living to care for others in life just as Qebhet did in the land of the dead.