The Amarna Period was an era of Egyptian history during the latter half of the Eighteenth Dynasty when the royal residence of the pharaoh and his queen was shifted to Akhetaten ('Horizon of the Aten') in what is now Amarna. It was marked by the reign of Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten (1353–1336 BC) in order to reflect the dramatic change of Egypt's polytheistic religion into one where the sun disc Aten was worshiped over all other gods. Aten was not solely worshiped (the religion was not monotheistic), but the other gods were worshiped to a significantly lesser degree. The Egyptian pantheon of the equality of all gods and goddesses was restored under Akhenaten's successor, Tutankhamun.

Religious developments

Akhenaten instigated the earliest verified expression of a form of monotheism, although the origins of a pure monotheism are the subject of continuing debate within the academic community. Some state that Akhenaten restored monotheism while others point out that he merely suppressed a dominant solar cult by the assertion of another, while never completely abandoning several other traditional deities. Scholars believe that Akhenaten's devotion to his deity, Aten, offended many in power below him, which contributed to the end of this dynasty; he later suffered damnatio memoriae. Although modern students of Egyptology consider the monotheism of Akhenaten the most important event of this period, the later Egyptians considered the so-called Amarna period an unfortunate aberration.

The period saw many innovations in the name and service of religion. Egyptians of the time viewed religion and science as one and the same. Previously, the presence of many gods explained the natural phenomena, but during the Amarna period there was a rise in monotheism. With people beginning to think of the origins of the universe, Amun-Re was seen as the sole creator and Sun-god. The view of this god is seen through the poem entitled "Hymn to the Aten":

From the poem, one can see that the nature of the god's daily activity revolves around recreating the earth on a daily basis. It also focuses on the present life rather than on eternity.

After the Amarna reign, these religious beliefs fell out of favor. It has been argued that this was in part because only the king and his family were allowed to worship Amun-Re directly, while others were permitted only to worship the king and his family.

Royal women

The royal women of Amarna have more surviving text about them than any other women from ancient Egypt. It is clear that they played a large role in royal and religious functions. These women were frequently portrayed as powerful in their own right.

Queen Nefertiti was said to be the force behind the new monotheist religion. Nefertiti, whose name means "the beautiful one is here," bore six of Amenhotep's daughters.

Many of Amenhotep's daughters were as influential or more than his wives. There is a debate whether the relationship between Amenhotep and his daughters was sexual. Although there is much controversy over this topic, there is no evidence that any of them bore his children. Amenhotep gave many of his daughters titles of queen.

Art

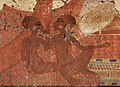

During Akhenaten's reign, royal portraiture underwent dramatic change. Sculptures of Akhenaten deviate from conventional portrayal of royalty. Akhenaten is depicted in an androgynous and highly stylized manner, with large thighs, a slim torso, drooping belly, full lips, and a long neck and nose. Some believe that the break with convention was due to "the presence at Amarna of new people or groups of artists whose background and training were different from those of the Karnak sculptors."

The events following Akhenaten's death are unclear and the identity and policies of his co-regent and immediate successor are the matter of ongoing scholarly debate.

Tutankhamun and the Amarna Succession

Tutankhamun, among the last of his dynasty and the Amarna kings, died before he was twenty years old, and the dynasty's final years clearly were shaky. The royal line of the dynasty died out with Tutankhamun. Two fetuses found buried in his tomb may have been his twin daughters who would have continued the royal lineage, according to a 2008 investigation.

An unidentified Egyptian queen Dakhamunzu, widow of "King Nibhururiya", is known from Hittite annals. She is often identified as Ankhesenamun, royal wife of Tutankhamun, although Nefertiti and Meritaten have also been suggested as possible candidates. This queen wrote to Suppiluliuma I, king of the Hittites, asking him to send one of his sons to become her husband and king of Egypt. In her letters she expressed fear and a reluctance to take as husband one of her servants. Suppiluliumas sent an ambassador to investigate, and after further negotiations agreed to send one of his sons to Egypt. This prince, named Zannanza, was, however, murdered, probably en route to Egypt. Suppiluliumas reacted with rage at the news of his son's death and accused the Egyptians. Then, he retaliated by going to war against Egypt's vassal states in Syria and Northern Canaan and captured the city of Amki. Unfortunately, Egyptian prisoners of war from Amki carried a plague which eventually would ravage the Hittite Empire and kill both Suppiluliumas I and his direct successor.

The last two members of the eighteenth dynasty – Ay and Horemheb – became rulers from the ranks of officials in the royal court, although Ay may have married the widow of Tutankhamun in order to obtain power and she did not live long afterward. Ay's reign was short. His successor was Horemheb, a general in the Egyptian army, who had been a diplomat in the administration of Tutankhamun and may have been intended as his successor by the childless Tutankhamun. Horemheb may have taken the throne away from Ay in a coup. He also died childless and appointed his successor, Paramessu, who under the name Ramesses I ascended the throne in 1292 BC and was the first pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Foreign relations

The Amarna Letters feature correspondence among the rulers of several empires, dubbed by modern historians The Club of Great Powers:Babylon, Assyria, Mitanni and Hatti, viz. the major powers in Mesopotamia, the Levant and Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age.

The Great Powers

Babylon EA 1-11

The Babylonians were conquered by an outside group of people and were referred to in the letters as Karaduniyas.[5] Babylon was ruled by the Kassite dynasty which would later on assimilate to the Babylonian culture. The letters of correspondence between the two deal with various trivial things but it also contained one of the few messages from Egypt to another power. It was the pharaoh responding to the demands of King Kasashman-Enlil, who initially inquired about the whereabouts of his sister, who was sent for a diplomatic marriage. The king was hesitant to send his daughter for another diplomatic marriage until he knew the status of his sister. The pharaoh responds by politely telling the king to send someone who would recognize his sister. Then later correspondence dealt with the importance of exchanging of gifts namely the gold which is used in the construction of a temple in Babylonia. There was also a correspondence where the Babylonian king was offended by not having a proper escort for a princess. He wrote that he was distraught by how few chariots there were to transport her and that he would be shamed by the responses of the great kings of the region.

Assyria EA 15-16

By the time of the Amarna letters, the Assyrians, who were originally a vassal state, had become an independent power. The two letters were from king Assur-uballit I. The first dealt with him introducing himself and sending a messenger to investigate Egypt: “He should see what you are like and what your country is like, and then leave for here.” (EA 15) The second letter dealt with him inquiring as to why Egypt was not sending enough gold to him and arguing about profit for the king: "Then let him (a messenger) stay out and let him die right there in the sun, but for (but) for the king himself there must be a profit."

Mittani EA 17–30

Once enemies, by the time of the Amarna letters, the Mittanni had become an ally of Egypt's. These letters were written by the King Tuiseratta and dealt with various topics, such as preserving and renewing marriage alliances, and sending in various gifts. For example, EA 22 and EA 25 in the Amarna letters are an inventory of the gifts from the Mittani king Tusratta to the pharaoh. Other correspondences of note dealt with a gold status that was addressed in EA 26 and EA 27. Akhenaten married a Mittani princess in order to create stronger ties between the two nations.

Hatti EA 41-44

Theirs was a kingdom in Eastern Anatolia that would later make the Mitanni their vassal state. The correspondence from the Hatti come from a king called Suppiluliumas. The subjects of the letters varied, from discussing past alliances to gift giving and dealing with honor. In EA 42, the tablet stated how the Hittite king was offended by the name of the pharaoh written over his name. Although the ending of the text was very fragmented, it was discerned as saying that he will blot out the name of the pharaoh.

Amarna Letters

The opening statement

|

William Moran discussed how the first line in these documents followed a consistent formula of “Say to PN. Thus PN.” There are variations of this but was found common among all the tablets. The other is a salutation which is one a report of the monarch's well being and then the second which is a series of good wishes toward the monarch. Indeed, this seems to be part of the style of Akkadian style of writing which helped facilitate foreign correspondence for the long term. As scholars argued, this aided in filtering out the chauvinistic domestic ideology at home to the other monarch. This allowed diplomacy to flourish which aided to the relative peace of the time.

Brotherhood

Despite the great distances between the rulers, the concept of a global village reigned.

|

The importance of this in EA 7 is that it demonstrates the mindset of the rulers in the Near East world at the time. The "enlarged village" which scholars like to term permeated their thoughts where they took the idea of brotherhood. They were related through the political marriages but is an idea of a village of clans which gives reason to the good wishes and update on the health of the monarchs themselves. The monarchs seem to have very little concept of the time of travel between each other and at most likely saw that the village worldview they lived in was applicable for the long distant correspondence of the Amarna letters. Indeed, there is a constant demonstration of love as seen in these letters. Scholars pointed out that to demonstrate good friendship it had to be on the practical level of constant stream of gift giving. This request for gifts is constant with the various correspondence with the Great Kings.