If we examine the doctrine concerning the future life according to the priesthoods of Rā we find still less room for a purgatory in their theological system. According to this the souls of the dead assembled in Ȧmentet, i.e., the “hidden” region, the Egyptian Hades, where they waited for the boat of Rā to pass by. When the god appeared those who had been his worshipers and adorers on earth, and who were fortunate enough to have secured the words of power which would enable them to enter the boat did so, and they made their journey with him through the Ṭuat.

If we examine the doctrine concerning the future life according to the priesthoods of Rā we find still less room for a purgatory in their theological system. According to this the souls of the dead assembled in Ȧmentet, i.e., the “hidden” region, the Egyptian Hades, where they waited for the boat of Rā to pass by. When the god appeared those who had been his worshipers and adorers on earth, and who were fortunate enough to have secured the words of power which would enable them to enter the boat did so, and they made their journey with him through the Ṭuat.

Under his protection they passed through all the dangers which threatened to destroy them, and continued their journey through the realms of Osiris and Seker, and at length appeared with Rā in the eastern horizon of heaven at daybreak. Once there they were able to wander about heaven at will, and they did so, presumably, until the time of sunset, when they rejoined the god in his boat, and again made the journey through the Ṭuat with him.

Each division of the Ṭuat, apparently, contained a host of beings who wished to enter the boat of Rā, but could not do so, either for want of the necessary words of power, or because they had reached the place to which their qualifications entitled them ; these all, however, received great benefit from the nightly visit of Rā, and as he left each division to enter the next they were filled with great sorrow, and many of them ceased to exist until the following night, when they renewed their life for a brief period.

Many divisions of the Ṭuat contained enemies of Rā, who were, of course, destroyed without mercy by the followers of the god ; but there is no reason whatsoever for the view that these enemies were the damned, or that they were doomed to eternal punishment.

At the end of the Ṭuat was a region where certain goddesses presided over pits of fire and superintended the destruction of the bodies, and spirits, and shadows, and heads of numbers of such enemies, and it would seem, judging by the knives in their hands, that they hacked the bodies to pieces before they were burnt. But even these were not punished eternally, for as soon as the god had passed through their region the fires went out, and the mere fact that he was able to appear in the eastern sky proved that all his enemies were destroyed. Each night and morning Rā destroyed the hosts of enemies who attempted to bar his progress, for such enemies perished instantly by the flames which went forth from the divine beings whom he had created.

Hell and the Damned

Originally, too, such enemies were only the personifications of the powers of nature, such as twilight, darkness, night, gloom, the blackness of eclipses, fog, mist, vapour, rain, cloud, storm, wind, tempest, hurricane, and the like, which were destroyed daily by Rā and his fiery beams. Many, in fact the greater number of such personifications, were endowed by Egyptian artists with human forms, and the pictures of the scenes of their destruction by fire were supposed by many to represent the burning of the souls of the damned.

The ignorant and the superstitious did not understand that the Sun-god slew and burned with fire the enemies of each night and morning during that same night and morning; each rising of the sun was the result of the annihilation of his foes of that day. It may be urged that these foes were always the same because they were always of the same kind, but the Egyptians did not think so, and they believed that a new host of foes appeared to attack Rā each night and morning.

But even had they thought so, the punishment was only intermittent, and it was only renewed during that part of each night which immediately preceded the dawn, and during the interval between dawn and sunrise. The souls of the damned could have done nothing to hinder the progress of Rā, and the Egyptians never imagined that they did, but it is possible that in late dynastic times certain schools of theological thought in Egypt, being dissatisfied with and unconvinced of the accuracy of the theory of the annihilation of the wicked, assigned to evil souls dwelling-places with the personifications of the powers of nature already-mentioned in the Ṭuat.

The spears which pierced the enemies of Rā were the fiery rays of the sun, and the knives which hacked their bodies in pieces were his flames of fire ; and the lakes and pits of fire were suggested to the minds of the primitive Egyptians by the fiery splendour which filled the eastern heavens at sunrise. They certainly did not believe in everlasting punishment, and there is nothing in the texts which will support the view that they did; in fact, the doctrines of purgatory and hell which were promulgated during the Middle Ages in Europe with such success find no equivalents in the ancient Egyptian religion.

Apart from the general characteristics of their religion the Egyptians were too practical to entertain the idea of repeated destructions or consumings by fire of the same body, but had they done so we should certainly have found some texts which had been composed to avert such an awful doom. They mummified the bodies of their dead in the earliest times because they expected them to rise again, and they did so in later times because they believed that a spiritual body would grow out of them ; they never expected to obtain a second physical body in the Underworld, and therefore they took the greatest care to preserve, by means of magical ceremonies and words, the bodies in which they lived in as complete a form as possible.

The destruction of the body involved the ruin of the Ka, or double, and of the shadow, and of many of the mental and spiritual constituents of man ; and the Egyptians regarded the death of the body with such dismay that, fearing lest the spiritual body which sprang from it after death might be in danger of dying, they caused prayers to be composed for the purpose of averting from it the “second death” and the possibility of its dying a second time.

Outer Darkness

We may see, however, that although the Egyptians had no hell for souls in the mediaeval acceptance of the term, their fiery pits, and fiends, and devils, and enemies of Rā formed the foundations of the hells of later peoples like the Hebrews, and even of the descendants of the Egyptians who became Christians i.e., the Copts. Many proofs of this fact may be found in Coptic literature as the following instances will show. In “Pistis Sophia,” we have the Virgin Mary asking Jesus, her Lord, to give her a description of “outer darkness,” and to tell her how many places of punishment there are in it.

Our Lord replies,

“The outer darkness is a great serpent, the tail of which is in its mouth, and it is outside the whole world, and surroundeth the whole world ; in it there are many places of punishment, and it containeth twelve halls wherein severe punishment is inflicted. In each hall is a governor, but the face of each governor differeth from that of his neighbour.

- The governor of the first hall hath the face of a crocodile, with its tail in its mouth. From the mouth of the serpent proceed all ice, and all dust, and all cold, and every kind of disease and sickness ; and the true name by which they call him in his place is Enkhthonin.

- And the governor of the second hall hath as his true face the face of a cat, and they call him in his place Kharakhar.

- And the governor of the third hall hath as his true face the face of a dog, and they call him in his place Arkharôkh.

- And the governor of the fourth hall hath as his true face the face of a serpent, and they call him in his place Akhrôkhar.

- And the governor of the fifth hall hath as his true face the face of a black ox, and they call him in his place Markhour.

- And the governor of the sixth hall hath as his true face the face of a goat, and they call him in his place Lamkhamôr.

- And the governor of the seventh hall hath as his true face the face of a bear, and they call him as his true name Lonkhar.

- And the governor of the eighth hall hath as his true face the face of a vulture, and they call him in his place Laraôkh.

- And the governor of the ninth hall hath as his true face the face of a basilisk, and they call him in his place Arkheôkh.

- And in the tenth hall there are many governors, and there is there a serpent with seven heads, each head having its [own] true face, and he who is over them all in his place they call Xarmarôkh.

- And in the eleventh hall there are many governors, and there are there seven heads, each of them having as its true face the face of a cat, and the greatest of them, who is over them, they call in his place Rhôkhar.

- And in the twelfth hall there are many great governors, and there are there seven heads, each of them having as its true face the face of a dog, and the greatest, who is over them, they call in his place Khrêmaôr.

These twelve governors are in the serpent of outer darkness, and each of them hath a name according to the hour, and each of them changeth his face according to the hour.”

The Hell of the Gnostics

It is quite clear that in the above extract from the famous Gnostic work we have a series of chambers in the outer darkness which has been borrowed from the twelve divisions of the Egyptian Ṭuat already described, and the reader has only to compare the vignettes to Chapters cxliv. and cxlv. of the Book of the Dead with the extract from “Pistis Sophia” to see how close the borrowing has been. An examination of another great Gnostic work, generally known as the “Book of Ieu,” proves that the Underworld of the Gnostics was nothing but a modified form of the Ȧmentet or Ȧmenti of the Egyptians, to which were added characteristics derived from the religious systems of the Hebrews and Greeks.

The Gnostic rivers and seas of fire are nothing but equivalents of those mentioned in the Book of the Dead, and the beings in Ȧmenti, and Chaos, and Outer Darkness are derived, in respect of form, from ancient Egyptian models. The great dragon of Outer Darkness and his twelve halls, and their twelve guardians or governors who change their names and forms every hour are, after all, only modifications of the old Egyptian system of the Twelve Pylons or Twelve Hours which formed the Underworld.

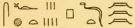

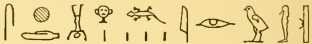

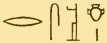

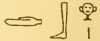

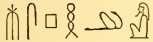

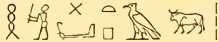

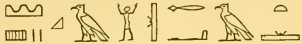

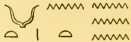

The seven-headed serpent of the Gnostic system has his prototype in the great serpent Nāu, , which is called the “bull of the gods,” and has

, which is called the “bull of the gods,” and has

, which is called the “bull of the gods,” and has

, which is called the “bull of the gods,” and has“seven serpents on his seven necks,”

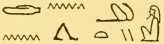

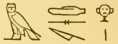

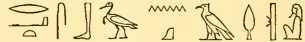

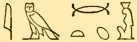

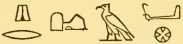

the seven-headed serpent, Nāu-shesmā,  , also had seven uraei for heads, and he had authority over seven archers, or seven bows,

, also had seven uraei for heads, and he had authority over seven archers, or seven bows,

.

.

, also had seven uraei for heads, and he had authority over seven archers, or seven bows,

, also had seven uraei for heads, and he had authority over seven archers, or seven bows,

.

.

Ȧmentet and the Ṭuat

Of Ȧmentet and the Ṭuat in general we find many traces in the martyrdoms of Coptic saints, but, as was to be expected, the writers have made the demons and the pits of fire of the Egyptian Underworld instruments of punishment for the souls of those who did not embrace Christianity when upon this earth.

Thus the writer of the Martyrdom of George of Cappadocia makes the saint to raise up from the dead a pagan called Boês, who had been dead two hundred years, and who told Dadianus, the governor, that he had been on earth a worshipper of the

“stupid, dumb, deaf, and blind Apollo,”

and that when he departed this life he went to live in

“a place in the river of fire until such time as I went to the place where the worm dieth not.”

According to another writer, Macarius of Antioch restored to life a man who had been dead for six hours, and who stated that his miseries during that short time had been greater than those which he had endured throughout all his life upon earth. He confessed that he had been a worshipper of idols, and then went on to say that when he was dying the fiends crowded upon him, and that these had the faces of serpents, lions, crocodiles, and, curiously enough, of bears.

They tore his soul from his body with great violence, and fled with it to a great river of fire wherein they plunged it to a depth of four hundred cubits ; then they drew it out and set it before the Judge of Truth, who passed sentence upon it.

After this was done they took it to a

“place of darkness, wherein there was no light whatsoever, and they cast it down into the cold where there was gnashing of teeth. Here,”

said the wretched man,

“I saw the worm which never slumbereth, and his head was like unto that of a crocodile. He was surrounded by serpents of every kind which cast souls before him, and when his own mouth was full he allowed the other creatures to eat; in that place they tore us to pieces, but we could not die. After that they took me out of the place and carried me into Ȧmenti, where I was to stay for ever.”

In another work a nameless mummy is made to tell how before he died the avenging angels came about him with iron knives and pointed goads, which they thrust into his sides, and how other angels came and tore his soul from his body, and having tied it to the similitude of a black horse they carried it off to Ȧmentet.

Here he was tortured in a place filled with noxious reptiles, and having been cast into the outer darkness he saw a pit more than two hundred feet deep, which was filled with reptiles, each of which had seven heads, and had its body covered with objects like scorpions. In this place were several other terrible serpents, and to one of these, which had teeth like iron stakes, the poor soul was given to be devoured ; this monster crushed the soul for five days of each week, but on Saturday and Sunday it had respite. This last sentence seems to suggest that the serpent respected the Sabbath of the Jews and the Sunday of the Christians.

Rā And Āpep

In all these examples, and even in the words of Isaiah, who says (lxvi. 24),

“their worm shall not die, neither shall their fire be quenched,”

we have a direct allusion to the great serpent of the Egyptian Underworld, which was, in all periods of history, the terror of the worshippers of the Sun-god, and which was known by many names. The allies and companions of this serpent were serpents like itself, and to nearly every power which was hostile to the dead or the living the form of a snake or serpent was attributed. The type and symbol of all enmity to Rā, whether of a physical or moral character, was the arch-serpent Āpep or Āpepi, which attacked him daily, and was overcome daily. To this monster we have several allusions in the Book of the Dead, but these do not adequately convey an idea of the terror with which he was regarded, at all events in the latter part of the dynastic period.

From a papyrus preserved in the British Museum we learn that a special service was in use in Upper Egypt for the purpose of destroying the power of Āpepi and of making his attacks on the sun to have no effect. This service consisted of a series of chapters which were to be recited at certain times of the day during the performance of a number of curious ceremonies of a magical character.

Thus one rubric orders that the name of Āpepi shall be written in green colour upon a piece of new papyrus, and that a wax figure of the fiend shall be made and his name inlaid upon it with green colour. Both papyrus and wax figure were to be burnt in the fire, the belief being that as the wax figure melted and as the sheet of papyrus burnt, the fiend Apepi would also decay and fall to pieces.

Whilst the wax figure was melting in the fire it was to be spit upon several times each hour, and when it was melted the refuse of it was to be mixed with dung and again burnt. It was imperative to do this at midnight, when Rā began his return journey in the Ṭuat, towards the east, and at dawn, and at noon, and at eventide, and in fact at any and every hour of the day. This might also be done with advantage whenever storm clouds appeared in the sky, or whenever the clouds gathered together for rain. The following extract will give an idea of the general import of the service for the destruction of Āpepi.

The deceased says :

“Apepi hath fallen into the flame, a knife is stuck into his head, his name no longer existeth upon this earth. It is decreed for me to inflict blows upon him, I drive darts into his bones, I destroy his soul in the course of every day, I sever his vertebræ from his neck, cutting into his flesh with a knife and stabbing through his skin.He is given over to the fire which obtains the mastery over him in its name of ‘Sekhet,’ and it hath power over him in its name of ‘Eye burning the enemy.’ Darts are driven into his soul, his bones are burnt with fire, and his limbs are placed therein.Horus, mighty of strength, hath decreed that he shall come in front of the boat of Rā ; his fetter of steel tieth him up and maketh his limbs so that they cannot move; Horus repulseth his moment of luck during his eclipse, and he maketh him to vomit that which is inside him.Horus fettereth, bindeth, and tieth up, and Aker taketh away his strength so that I may separate his flesh from his bones ;

that I may fetter his feet and cut off his two hands and arms ;

that I may shut up his mouth and lips, and break in his teeth ;

that I may cut out his tongue from his throat, and carry away his words ;

that I may block up his two eyes, and carry off his ears ;

that I may tear out his heart from its seat and throne ;

and that I may make him so that he existeth not.May his name never exist, and may what is born to him never live ; may he never exist, and may his kinsfolk never exist; may he never exist, and may his relatives never exist; may he never exist, and may his heir never exist; may his offspring never grow to maturity; may his seed never be established ; moreover, may his soul, and body, and spirit, and shade, and words of power, and his bones, and his skin, never more exist.”

The Rubric runs :

“This Chapter is to be said over a figure of Āpepi, inscribed upon new papyrus with green ink, and placed inside a covering on which his name hath been written, and thou shalt tie these round tightly with cord, and put such a figure and covering into the fire every day.Thou shalt stamp upon it and defile it with thy left foot, and thou shalt spit upon it four times during the course of every day, and when thou hast placed it upon the fire thou shalt say,‘Rā triumpheth over thee, Āpepi, and Horus triumpheth over his enemies, and P-āa (i.e., the deceased) triumpheth over his enemies.’Next thou shalt write down the names of all the male and female devils of which thy heart is afraid, the names of all the enemies of P-āa, in death, and in life, and the names of their father, mother, and children, [and place the papyrus] inside the covering, together with a wax figure of Āpepi.These shall then be placed in the fire in the name of Āpepi, and shall be burnt when Rā riseth in the morning; this thou shalt repeat at noon and at evening when Rā setteth in the land of life, whilst there is light at the foot of the mountain. Over each figure of Āpepi thou shalt recite the above chapter, in very truth, for the doing of this shall be of great benefit [for thee] upon earth and in the Underworld.”

Serpents and Snakes

To destroy the fiends which were associated with Āpepi it was necessary to make figures of them in wax, and having inscribed their names upon them to tie them round with black hair, and then to cast them on the ground, and kick them with the left foot, and pierce them with a stone spear.

To obtain the full benefit of all the names of Āpepi a man had to make the figure of a serpent with his tail in his mouth, and having stuck a knife in its back, and cast it down upon the ground, to say,

“Āpep, Fiend, Betet.”

The faithful follower of Rā is also bidden to

“make another serpent with the face of a cat, and with a knife stuck in his back, and call it Hemhem.

Make another with the face of a crocodile, and with a knife stuck in his back, and call it Hauna-ȧru-ḥer-ḥrȧ;

make another with the face of a duck, and with a knife stuck in his back, and call it Aluti.

Make another with the face of a white cat, and with a knife stuck in his back, and tie it up and bind it tightly, and call it ‘Āpep the Enemy.’”

The papyrus which contains these interesting passages was written about B.C. 312-311, though the compositions in it are very much older, but it shows that, even at that period, when the Macedonians had begun to reign over Egypt, and Greek influence was making itself supreme in the country, the old beliefs still held sway over the minds of the Egyptians. In fact, in this matter as in nearly all others, they clung most tenaciously to the views and opinions of their forefathers.

The primitive Egyptians feared snakes and propitiated them, and the earliest dynastic people of the country employed charms, and incantations, and magical formulae to keep snakes, and serpents, and reptiles of every kind from their dead; the priests of Heliopolis respected the prevailing views of their countrymen, and ancient formulae against snakes were copied into their funeral texts. Every Recension of the Book of the Dead contained Chapters which were written to preserve the dead from the attacks of snakes ; it is tolerably certain that some of them contain formulae which are not older than dynastic times, and these show that the fear of serpents was as great as ever, although these reptiles cannot have been so numerous as formerly.

The priests of Ȧmen made snakes to play very prominent parts in the Underworld, and, curiously enough, they thought that the dead Sun-god, or the “Flesh of Rā,” was re-born into the life of a new day, only after he had been drawn in his boat through the body of a serpent.

The Egyptians usually had some reason for the things they said, and wrote, and depicted, and although it is not easy to find the reason in every case, there is, fortunately, little doubt about it here. They observed that snakes sloughed their skins from time to time, and that their bodies were much improved in appearance as the result, and it is pretty certain that they had this habit of snakes in their minds, when they made their god Rā as a new being to emerge in his boat out of the great serpent which lay in deep undulations between the end of the Ṭuat and this world.

Ṭuat and Gehenna

Reference has already been made to the influence upon the hell of the Copts of the old Egyptian mythology about the Ṭuat, and it is right here to point out that the Hebrews appear to have borrowed from it many of their ideas concerning the abodes of the dead in the Underworld. It is quite certain that the hell of which they conceived the existence was not derived from the Babylonians, for we know from the story of Ishtar’s descent into the “land of no return” that, although it had Seven Gates, it contained no pits of fire or monster serpents.

Ishtar, we are told, found it to be a place of darkness, and she saw that the beings in it were dressed in garments of feathers, and that dust and mud were their food. The commonest of the names which the Hebrews gave to the abode of the damned is Gề Hinnom, or Gehenna, which was originally the Valley of Hinnom, that lay quite near to Jerusalem, where children were sacrificed to the god Moloch; this name passed into the New Testament under the form Τεέννα, and into Arabic literature as “Jahannam.”

The portion of the Valley of Hinnom where the sacrifices were burnt was called “Tôpheth.” According to the Rabbis “Gehenna” was created on the second day of creation, with the firmament and the angels, and just as there were an Upper and a Lower Paradise so there were also two Gehennas, one in the heavens and one on the earth.

As to the size of Gehenna we read that Egypt was 400 parassangs long and 400 parassangs wide, i.e., about 1,200 miles long by 1,200 miles wide; that Nubia ( ) was sixty times as large as Egypt; that the world was sixty times as large as Nubia, and that it would require 500 years to travel across either its length or its breadth; that Gehenna was sixty times as large as the world ; and that it would take a man 2,100 years to reach it.

) was sixty times as large as Egypt; that the world was sixty times as large as Nubia, and that it would require 500 years to travel across either its length or its breadth; that Gehenna was sixty times as large as the world ; and that it would take a man 2,100 years to reach it.

) was sixty times as large as Egypt; that the world was sixty times as large as Nubia, and that it would require 500 years to travel across either its length or its breadth; that Gehenna was sixty times as large as the world ; and that it would take a man 2,100 years to reach it.

) was sixty times as large as Egypt; that the world was sixty times as large as Nubia, and that it would require 500 years to travel across either its length or its breadth; that Gehenna was sixty times as large as the world ; and that it would take a man 2,100 years to reach it.

Halls of Gehenna

In Gehenna, as in Paradise, there were seven “palaces” ( ), and the punishments which were meted out to their inhabitants varied both in kind and in intensity. In each palace there are 6,000 houses, or chambers, and in each house are 6,000 boxes, and in each box are 6,000 vessels fitted with gall. Gehenna is so deep that it would take 300 years to reach -the bottom of it; according to another opinion it is 300 miles long, 300 miles wide, 1,000 miles thick, and 100 miles deep. The fire in each palace is fiercer and more destructive than that in the palace preceding, and the flames of the deepest portion of it are able to consume human souls utterly, which fire upon earth can never do.

), and the punishments which were meted out to their inhabitants varied both in kind and in intensity. In each palace there are 6,000 houses, or chambers, and in each house are 6,000 boxes, and in each box are 6,000 vessels fitted with gall. Gehenna is so deep that it would take 300 years to reach -the bottom of it; according to another opinion it is 300 miles long, 300 miles wide, 1,000 miles thick, and 100 miles deep. The fire in each palace is fiercer and more destructive than that in the palace preceding, and the flames of the deepest portion of it are able to consume human souls utterly, which fire upon earth can never do.

), and the punishments which were meted out to their inhabitants varied both in kind and in intensity. In each palace there are 6,000 houses, or chambers, and in each house are 6,000 boxes, and in each box are 6,000 vessels fitted with gall. Gehenna is so deep that it would take 300 years to reach -the bottom of it; according to another opinion it is 300 miles long, 300 miles wide, 1,000 miles thick, and 100 miles deep. The fire in each palace is fiercer and more destructive than that in the palace preceding, and the flames of the deepest portion of it are able to consume human souls utterly, which fire upon earth can never do.

), and the punishments which were meted out to their inhabitants varied both in kind and in intensity. In each palace there are 6,000 houses, or chambers, and in each house are 6,000 boxes, and in each box are 6,000 vessels fitted with gall. Gehenna is so deep that it would take 300 years to reach -the bottom of it; according to another opinion it is 300 miles long, 300 miles wide, 1,000 miles thick, and 100 miles deep. The fire in each palace is fiercer and more destructive than that in the palace preceding, and the flames of the deepest portion of it are able to consume human souls utterly, which fire upon earth can never do.

Each palace is, according to one view, under the command of an angel, who is subservient to Dûmâh, the prince of Gehenna, and who has with him tens of thousands of angels who are occupied in judging sinners and sealing their doom; but according to another the seven mansions are ruled, under Dûmâh, , by three angels called Mashkhîth, Af, and Khêmâ. The voices of the beings in Gehenna rise up to heaven mingled with the cries of the wicked.

, by three angels called Mashkhîth, Af, and Khêmâ. The voices of the beings in Gehenna rise up to heaven mingled with the cries of the wicked.

, by three angels called Mashkhîth, Af, and Khêmâ. The voices of the beings in Gehenna rise up to heaven mingled with the cries of the wicked.

, by three angels called Mashkhîth, Af, and Khêmâ. The voices of the beings in Gehenna rise up to heaven mingled with the cries of the wicked.

Dûmâh, the prince of Gehenna, seems to have been of Egyptian origin, for we read,

“At the time when Moses said,‘I will perform judgments on all the gods of Egypt,’Dûmâh, the prince of Egypt, went 400 miles and God said unto him,‘This decree is decreed by me, even as it is written, I will visit the host of the height in the height;’and in that same hour sovereignty was taken away from him, and he was appointed prince over Gehenna, and some say that he was set over the dead.”

Another prince of Gehenna was called ‘Arsîêl, and his duty was to stand before the souls of the righteous to prevent them from praying to God on behalf of the wicked. Opinions vary as to the number of gates or doors which are in Gehenna, some saying there are 50, others 8,000, and others 40,000 ; but the writers who followed the best traditions fixed the number at seven, and this agrees with the best Muhammadan tradition also. Finally, as a river runs through the Ṭuat so a river or canal flows through Gehenna.

The first division of Gehenna is 100 miles long and 50 miles wide, and it contains several pits wherein fiery lions dwell; when men fall into the pits the lions consume parts of them and the fire devours the remainder, but soon afterwards they come into being again and have to pass through the fire which is in the second division, when they are again consumed and again come to life. In this way they have to pass through the fire of all the seven divisions. According to another opinion one half of Gehenna is fire and the other half hail, and the angel who is in charge drives the souls of the damned from the fire into the hail and from the hail into the fire without ceasing.

Another writer says that each of the seven divisions of hell contains seven streams of fire and seven streams of hail, and that each division is sixty times as large as that which is immediately above it. In each division are 7,000 small chambers, and in each chamber 7,000 clefts, and in each cleft 7,000 scorpions, and in each scorpion seven joints, and in each joint 1,000 vessels of gall; through it flow seven rivers filled with deadly poison, and the damned have to pass one half of the year in the fire, and the other half in the hail and snow, which are far more terrible than the fire.

Moreover, from under the throne of God Almighty there goes forth a river of fire which empties itself upon the heads of the wicked, but most of these have a rest from their punishment for one hour and a half three times a day, i.e., at the times of morning, mid-day, and evening prayer, and they have rest the whole of each Sabbath and of each festival of the new moon. Some of the Rabbis believed that the punishment of the wicked would last for ever, but others thought that a period of punishment six or twelve months in length would suffice for their purification.

Ṭuat and Gehenna

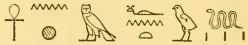

Those who are damned shall not remember the names which they bore upon earth, and although the angels beat them and call upon them to declare their names, they shall not be able to do so ; this view was clearly held by the Egyptians, for we are specially told in the text of Pepi I. (line 169),

“Pepi is happy with his name,”

From the facts recorded above it is easy to see how much the Hebrews were indebted to the Egyptians in the construction of their Gehenna, and how closely they fitted native beliefs into a framework of foreign conceptions. Some of their writers seem to have possessed a better insight into such matters than others, whilst a few of them unconsciously reproduced the original conception of the Ṭuat as the place of destruction for the enemies of the god, and believed that Gehenna, or hell, would be abolished.

These thought that at some future time God would remove the sun from its place and would place it in the second firmament, in a hollow place or chamber specially prepared for it, and that having judged and condemned the wicked He would send them into this chamber, where the burning heat of the sun would consume them.

The Rabbis generally took no pains to say either how the fires of Gehenna were started, or how they were maintained, but Rabbi Yannai and Rabbi Shim‘ôn ben-Lakîsh evidently thought it out, and so reduced Gehenna, unintentionally, to the place where a physical sun supplied the consuming fire, and did for the damned among the Hebrews exactly what it did for the enemies of Rā among the Egyptians.

It must be noted that the Gehenna of the Hebrew lacked the serpents of the Egyptian Ṭuat, but when we consider the difference between the physical characteristics of Egypt and those of Syria and Palestine this is not to be wondered at. In predynastic times Egypt was filled with serpents of every kind, and the terror which they inspired lived in the minds of the people of dynastic times long after the country had been practically cleared from these reptiles.

In Palestine and Syria snakes were never very plentiful, but in the region of Southern Babylonia, whence came Abraham and his companions, they must have existed in large numbers. It is a curious fact that the Hebrews, who borrowed so largely in their cosmogony from Babylonian sources, did not also borrow in some form or other the monster Tiamat, which played in their mythology the same part that Āpep or Āpepi played among the Egyptian gods.

The Babylonian Tiamat waged war against Marduk, the champion chosen by the gods, and was held to be the incarnation of all evil, both physical and moral; and although the Hebrews assigned to the serpent cunning and guile, and declared that he was “more subtle than any beast” (Gen. iii. 1), they hardly considered him to be a great physical power which waged war against the sun daily.

Āpep And Tiamat

Tiamat, as we learn from a cuneiform text, was 50 kasbu long, and the height of its undulations was 1 kasbu; its mouth was one-half a gar, or six cubits wide, and it moved in water 9 cubits deep. Three other measurements are given, viz., 1 gar, 1 gar, and 5 gar, but as the text following them is broken it cannot be said to what they refer. Now, the kasbu was the distance usually passed over in a journey of two hours, and the cubit may be considered to be about 20 inches. Reckoning the kasbu at six miles we thus have a monster 300 miles long, which had a mouth 10 feet wide, and which moved in undulations six miles high ! The measurements of 5 gar probably refers to its girth, and if this be so the creature was 100 feet round its body.

When Tiamat had been slain we are told that its blood flowed from its body for three years, three months, and one day, and we are able to obtain an idea of its huge size from the statement that when Marduk had smashed in its skull with his club, and had slit the channels of its blood, he split it, like a flat fish, into two halves, one of which he made use of to form the “covering of the heavens.”

There is no doubt that originally the Babylonian Tiamat was nothing but the rain clouds, and the mist and fog which lie over the Tigris and Euphrates in the early morning at certain seasons of the year, and which when i looked at from the desert appear like a huge serpent stretched along the length of the stream, both up and down the river. The Hebrew Scriptures contain several allusions to a great nature serpent, though he finds no place among the Seven Mansions of their hell.

Thus the prophet Amos (ix. 3) refers to the serpent at the bottom of the sea, which Yahweh would command to bite the wicked if they attempted to hide there ; in Psalm lxxiv. 13 f. God is referred to as the breaker of the heads of Leviathan and of the dragons in the waters ; in Isaiah (li. 9).we have,

“Awake, awake, put on strength, O arm of Yahweh ! Awake, as in the ancient days, in the generations of old ! Art thou not it that did slay the monster Râhắbh, and wound the serpent (tannîn) ?”

Râhâbh may here, as some have argued, refer to Egypt, but if so, it is to Egypt as the home of the great serpent monster which we now know as Āpepi, and which was to the prophet Isaiah the type and symbol of the country, and not to the judgments which Yahweh meted out to that land.

Āpep, Tiamat, Leviathan

The Hebrew writers refer to the nature serpent under several names, e.g., tannîn, nakhash, râhâbh, but the monster referred to under them is, in reality, one and the same, i.e., Leviathan ( livyâthân), “the serpent of many twistings or folds,” and both Nebuchadnezzar II. and the “King of Assyria” are identified with him (see Jeremiah li. 34 ; Isaiah xiv. 29). According to the Rabbis he was created on the fifth day of the week of creation, and was hunted for slaughter by Gabriel, and with the assistance of Yahweh was slain by him ; here we have a series of close resemblances to the history of Tiamat, for Gabriel is in every way the counterpart of Marduk, and Yahweh takes the place of Anshar as the head of the gods.

livyâthân), “the serpent of many twistings or folds,” and both Nebuchadnezzar II. and the “King of Assyria” are identified with him (see Jeremiah li. 34 ; Isaiah xiv. 29). According to the Rabbis he was created on the fifth day of the week of creation, and was hunted for slaughter by Gabriel, and with the assistance of Yahweh was slain by him ; here we have a series of close resemblances to the history of Tiamat, for Gabriel is in every way the counterpart of Marduk, and Yahweh takes the place of Anshar as the head of the gods.

livyâthân), “the serpent of many twistings or folds,” and both Nebuchadnezzar II. and the “King of Assyria” are identified with him (see Jeremiah li. 34 ; Isaiah xiv. 29). According to the Rabbis he was created on the fifth day of the week of creation, and was hunted for slaughter by Gabriel, and with the assistance of Yahweh was slain by him ; here we have a series of close resemblances to the history of Tiamat, for Gabriel is in every way the counterpart of Marduk, and Yahweh takes the place of Anshar as the head of the gods.

livyâthân), “the serpent of many twistings or folds,” and both Nebuchadnezzar II. and the “King of Assyria” are identified with him (see Jeremiah li. 34 ; Isaiah xiv. 29). According to the Rabbis he was created on the fifth day of the week of creation, and was hunted for slaughter by Gabriel, and with the assistance of Yahweh was slain by him ; here we have a series of close resemblances to the history of Tiamat, for Gabriel is in every way the counterpart of Marduk, and Yahweh takes the place of Anshar as the head of the gods.

Finally, Leviathan was slain by Gabriel, just as Tiamat was killed by Marduk, and out of the skin of Leviathan Gabriel made a tent wherein the righteous might dwell, and a covering for the walls of the city of Jerusalem. This covering was bright and shining, and it emitted light which was so strong that it could be seen from one end of the world to the other.

The last statement recalls the words of the Fourth Tablet of the Creation Series, which tell how Marduk made a canopy in the heavens of one-half of the body or skin of Tiamat. In the Hebrew version of the story it is said that the righteous feed upon the body of Leviathan, but there is no equivalent passage in the cuneiform texts at present known. From the passage in the Psalm already quoted (lxxiv. 13) it would appear that Leviathan had many heads, but this view is not supported by any known description of Tiamat, and in the absence of any evidence on the subject we must assume that the idea of a plurality of heads came from Egypt.

In the Book of Revelation (xii. 3 ; xiii. 1) mention is made of a “great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads,” which appeared in heaven, and of a beast having seven heads and ten horns, with ten crowns upon his horns, which came up out of the sea, but the idea of these also was not derived from Babylonia. All the available evidence goes to show that whilst the Hebrew conception of Leviathan was of Babylonian origin that of a hell of fire was borrowed from Egypt.

Seven-headed Serpent

Similarly, the seven-headed dragon and beast of the Book of Revelation, like the seven-headed basilisk serpent mentioned in “Pistis Sophia,”[28] have their origin in the seven-headed serpent which is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts. In Revelations ix. 19, horses are referred to which had tails “like unto serpents, and had heads,” and here again we have an idea suggested by a monster which inhabited one of the Pylons of the Ṭuat, and which had the body of a crocodile and a tail formed of a writhing serpent’s body with a serpent’s head for the tip of it.

Gnostic Magical Names

But although the Hebrews borrowed the framework of their hell from Egypt they appear to have made no use of the means by which the Egyptians hoped to escape from Amentet and the Ṭuat, that is to say, there is no evidence to show that they had in early times any equivalent for the system of words of power which played such an important part in the magical side of the Egyptian religion. On the other hand, the Copts, at least those of them who belonged to Gnostic sects, retained the beliefs concerning the efficacy of magical words and names, and they introduced them into their writings in a remarkable manner.

Thus in “Pistis Sophia” we are told that after His resurrection Jesus stood up with His disciples by the sea, and prayed to His Father, whom He addressed by a series of magical names, thus:—

- Aeêiouô,

- Iaô,

- Aôi,

- Ôiapsinôther,

- Thernops,

- Nôpsiter,

- Zagourê,

- Pagourê,

- Neth-momaôth,

- Nepsiomaôth,

- Marakhakhtha,

- Thôbarrabau,

- Thar-nakhakhan,

- Zorokothora,

- Ieou,

- Sabaoth.

Whilst He was saying these names Thomas, Andrew, James, and Simon the Canaanite stood in the west with their faces towards the east; and Philip and Bartholomew stood in the south with their faces towards the north.

In another passage Jesus addresses His Father in these words and by these names :—

- Iaô Iouô,

- Iaô,

- Aôi,

- Ôia,

- Psinôther,

- Therôpsin,

- Ôpsither,

- Nephthomaôth,

- Nephiomaôth Marakhakhtha,

- Marmarakhtha,

- Iêana menaman,

- Amanêi tou ouranou,

- Israi Ḥamên Ḥamên,

- Soubaibai appaap Ḥamên Ḥamên,

- deraarai Ḥapaḥou Ḥamên Ḥamên,

- Sarsarsartou Ḥamên Ḥamên,

- Koukiamin miai Ḥamên Ḥamền,

- Iai,

- Iai,

- Toua Ḥamên Ḥamên Ḥamên,

- Main-mari,

- Mariê,

- Marei Ḥamên Ḥamên Ḥamên.

- In another place

- Siphirepsnikhieu,

- Zenei,

- Berimou,

- Sokhabrikhêr,

- Euthari,

- Nanaï Dieisbalmêrikh,

- Meunipos,

- Khirie,

- Entair,

- Mouthiour,

- Smour,

- Peukhêr,

- Oouskhous,

- Minionor,

- Isokhobortha ;

and immediately afterwards He calls upon the Powers of His Father by these names :—

- Auêr,

- Bebrô,

- Athroni,

- Êoureph,

- Êône,

- Souphen,

- Knitousokhreôph,

- Mauônbi,

- Mneuôr,

- Souôni,

- Khôkheteôph,

- Khôkhe,

- Eteôph,

- Memôkh,

- and Anêmph.

An examination of the books of “Pistis Sophia” will show that many of the details of the “mysteries” which are there described are based upon ancient Egyptian beliefs, and that the whole of the doctrine of spiritual light which is expounded therein only represents a spiritualized conception of the far-reaching character of the powers of the light of the sun upon both the living and the dead, which the dynastic Egyptians recognized and described centuries before the Christian era.

This was expressed in the terms of a highly artificial system wherein words of power, magical names, emanations, ranks of angels, gates, watchers, and purely Christian conceptions were mixed up together, with the Lord Christ as the central Figure. Much has yet to be done before all the comparisons and connections between the Egyptian and Christian systems can be fully worked out, but the facts quoted above will, perhaps, suggest the importance of the study.

, which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned.

, which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned. , i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties.

, i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties. , supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men.

, supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men. , were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile.

, were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile. , or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort.

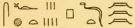

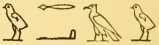

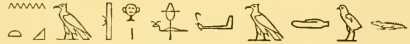

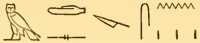

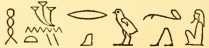

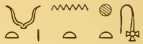

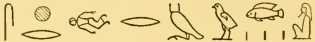

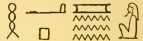

, or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort. , sekhet,

, sekhet, , nut,

, nut, , ārret,

, ārret, , qerert.

, qerert. .

. .

.

.

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

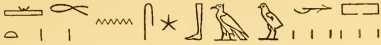

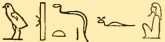

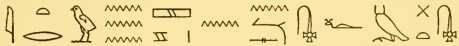

, or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god.

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

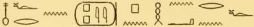

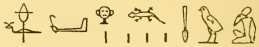

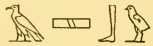

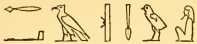

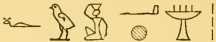

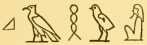

. ) I. Sekhet Ȧarru; its god was Rā-Heru-khuti.

) I. Sekhet Ȧarru; its god was Rā-Heru-khuti. ; its god was Fa-ākli,

; its god was Fa-ākli,  .

. .

. .

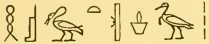

. ; the god in it is called Sekher-remu,

; the god in it is called Sekher-remu,  .

. .

. ; the god in it is Fa-pet,

; the god in it is Fa-pet,  .

.

.

. ; the god in it is Sepṭ,

; the god in it is Sepṭ,  .

. ; the god in it is Ḥetemet-baiu,

; the god in it is Ḥetemet-baiu,  .

. ; the god in it is Āa-sekhemu,

; the god in it is Āa-sekhemu,  .

. ; the god in it is Ḥāp,

; the god in it is Ḥāp,  i.e., the Nile.

i.e., the Nile. .

. ; the god in it is Maa-thet-f,

; the god in it is Maa-thet-f,  .

. ,” wherein the gods live upon cakes and ale.

,” wherein the gods live upon cakes and ale.