Chapter V - The Underworld

In the chapters on God and the gods it has already been said that the Egyptians in the earliest times believed that the gods were moved by the same passions as men and grew old and died like men ; later, however, they believed that it was only the bodies of the gods which died, and they therefore provided in their religious system a place for the souls of dead gods, just as they provided a place for the souls of dead men and women.

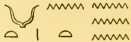

The writers of the religious texts were not all agreed as to the exact position of this place, but from first to last, whatever might be the conceptions entertained about it, it was called Ṭuat.

This word is commonly rendered “underworld,” but it must be distinctly understood that the Egyptian word does not imply that it was situated under our world, and that this rendering is only adopted because the exact signification of the name Ṭuat is unknown. The word is a very old one, and expresses a conception which was originated by the primitive Egyptians, and was probably unknown to their later descendants, who used the word without troubling to define its exact meaning.

To render Ṭuat by “hell” is also incorrect, because “hell” conveys to modern peoples ideas which were foreign to the Egyptians of most schools of religious thought. Whatever may be the moral ideas of the Ṭuat as a place of punishment for the wicked in later times, it is clear that at the outset it was regarded as the place through which the dead Sun-god Rā passed after his setting or death each evening on his journey to that portion of the sky in which he rose anew each morning.

In the XlXth Dynasty we know that the Ṭuat was believed to be situated not below our earth, but away beyond the earth, probably in the sky, and certainly near the heaven wherein the gods dwelt; it was the realm of Osiris who, according to many texts, judged the dead there, and reigned over the gods of the dead as well as over the dead themselves.

The Ṭuat

The Ṭuat was separated from this world by a chain or range of mountains, and consisted of a great valley, which was shut in closely on each side by mountains; the mountains on one side divided the valley from this earth, and those on the other divided it from heaven.

We may note in passing that the Hebrews separated the blessed from the damned by a wall, and that Lazarus was separated from Dives in hell by a “great gulf,” and that the Muhammadans divide heaven from hell by the mountain Al-A‘râf,  , which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned.

, which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned.

, which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned.

, which, however, cannot be of any great breadth because those who stand upon it are supposed to be able to hold converse both with the blessed and the damned.

It is pretty certain that both Hebrews and Muhammadans borrowed their ideas of the partition between heaven and hell from the Egyptian Ṭuat, but there is no authority in the texts for the Muhammadan view that it is a sort of limbo or purgatory for those who are too good for earth but not good enough for heaven. Those who stand on Al-A‘râf are said to be angels in the form of men, patriarchs, prophets, and saints, and those whose good deeds on earth were exactly counterbalanced by their evil deeds, and who therefore merit neither heaven nor hell.

Through the valley of the Ṭuat runs a river, which is the counterpart of the Nile in Egypt and of the celestial Nile in heaven, and on each bank of this river lived a vast number of monstrous beasts, and devils, and fiends of every imaginable kind and size, and among them were large numbers of evil spirits which were hostile to any being that invaded the valley.

On the sarcophagus of Seti I. is a representation of the Creation, which is reproduced on p. 204, and from it we see that the Ṭuat is likened to the body of Osiris, which is bent round like a hoop in such a way that his toes touch the back of his head.

On the top of his head stands the goddess Nut, who supports with both hands the disk of the sun. From this we may conclude both that Osiris is the personification of the Ṭuat, and that the Ṭuat is a narrow circular valley which begins where the sun sets in the west, and ends where he rises in the east.

The Ṭuat was a terrible place by reason of the monsters and devils with which it was filled, and its horrors were increased by the entire absence of light from it, and the beings therein groped about in the darkness of deep night. That the Ṭuat should be a place of blackness and gloom is quite natural when once we have realized that it was the path of the dead sun between the sunset of one day and the sunrise of the following day.

The ideas about this region, which we find reproduced in papyri of the New Empire, belong to different periods, and we can see that the Theban writers who described it and drew pictures of the beings which lived in it, collected a mass of legends and myths from every great religious centre of Egypt, wishing to make them all form part of their doctrine concerning the great god of Thebes, Ȧmen-Rā.

As the priests of Heliopolis succeeded in promulgating their theological system throughout the length and breadth of Egypt by identifying the older gods with their gods, and by proving that their views included those of all the priesthoods of the great cities of Egypt, so the priests of Thebes endeavored to convince the priests of other great cities of the superiority and greatness of their God Ȧmen-Rā, and probably succeeded in so doing.

The Ṭuat and Ȧmentet

The Theban writers and scribes knew perfectly well that originally every nome or great city possessed its own underworld just as it possessed its own company of gods, and that each underworld was designated by a special name; they, therefore, made the Ṭuat to include all these underworlds and all the various gods with whom they were peopled, and they gave it the most important of the names of the local underworlds.

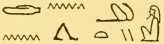

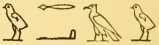

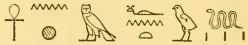

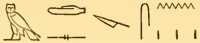

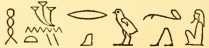

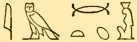

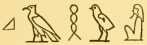

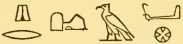

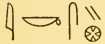

The best known of these was Ȧmentet,  , i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties.

, i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties.

, i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties.

, i.e., the “hidden place,” which appears to have been originally the place where Ȧn-ḥer, the local god of Abydos, ruled as god of the dead, under the title of “Khenti Ȧmentet,” that is to say, “he who is the chief of the unseen land.” When the importance of Ȧn-ḥer was eclipsed by the new-comer Osiris, the title of the former was assigned to Osiris, who, henceforth, was always called “Khenti Ȧmentet.” But this usurpation of Ȧn-ḥer’s title as god of the dead by Osiris must have taken place in very early times, for ȧmentet was a common name for the underworld throughout Egypt, and is found in texts of all periods, even in those of the Vth and VIth Dynasties.The Ṭuat and its Inhabitants

Yet long before even this remote period the priesthoods of certain nomes or cities must have developed the idea that the life of a man resembled the course of the sun during the day, and that setting was to the sun what death was to a man ; the sun, however, reappeared each morning in apparently a new body, and as man wished to live again in a renewed, or new, body, the Egyptian theologians set to work to form a system of theology in which the souls of the blessed dead, i.e., those who had been buried with all the ceremonies prescribed by the religion of the period, were made to accompany the sun in his boat as he passed through the portion of the Ṭuat which had been assigned to them.

As the sun passed through the Ṭuat large numbers of souls made their way into his boat, and although it was only the dead sun that was their guide and protector, and his passage was through the realms of the dead which were under the sovereignty of Osiris, the god of the dead, they were brought forth at length to renewed life and light as soon as the boat passed out from the eastern end of the Ṭuat into the day. This view was a very popular and widespread one, especially as it made Rā and Osiris Work together, each after his own method, to secure eternal life and happiness for the souls of the dead.

As soon as the priests had made up their minds that the Ṭuat existed, they began to people it with imaginary beings which were supposed to be hostile to the souls of the dead, and to invent descriptions of the various regions into which they declared it was divided; such descriptions were at length committed to writing, at first in a very simple form, and after the manner of every group of texts which were composed for the benefit of the dead, but finally they became more elaborate, and attempts were made to represent pictorially the creatures which were found in the Ṭuat.

In fact, it was intended to compile a book which should contain such accurate descriptions of the Ṭuat, and such true pictures of the foes which the dead soul would have to meet there, together with lists of their names, that when a soul was once provided with a copy of it he would find it impossible to lose his way, or to be overcome by any monster which attempted to bar his way or to prevent his access to the boat of Rā.

The Shāt Ȧm Ṭuat

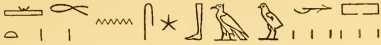

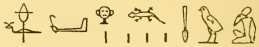

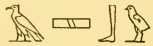

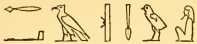

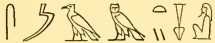

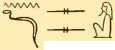

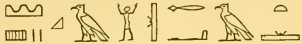

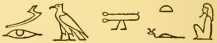

The great work which the Egyptians called “Coming Forth by Day,”  , supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men.

, supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men.

, supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men.

, supplied the soul with a great many words of power, and prayers, and incantations, as well as hymns, but even in the Early Empire, about B.c. 3500, many of its doctrines were antiquated, and the priests found it necessary to add new chapters and to modify old ones in order to make it a funeral work suitable for the requirements of newer generations of men.

Owing to the extreme antiquity of the “Book of Coming Forth by Day,” the views expressed in many of its chapters were contrary to those held by Theban priests of the New Empire, about B.c. 1050, and as a result, whilst preserving, and holding in great reverence this work which they had borrowed from the ancient priesthood of Heliopolis, they compiled two works, which may be called

- “The Book of that which is in the Ṭuat,”

- and the “Book of the Pylons.”

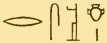

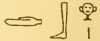

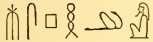

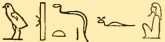

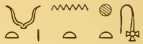

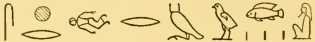

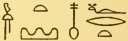

In the first of these, the “Shāt ȧm Ṭuat,”  , were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile.

, were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile.

, were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile.

, were gathered together all the views held by the Heliopolitan priesthood on the life of man’s soul after death, and though it contained all the doctrines as to the supremacy of Rā, their great Sun-god, these were so skilfully manipulated by the Theban priests, that the compilation actually became a work which magnified the grade and influence of Ȧmen-Rā, the great god of Thebes, and raised him to the position which the Thebans claimed for him, namely, “king of the gods, and lord of the thrones of the two lands.” The thrones here referred to are not those of kings, but the shrines of all the gods on all the land on each side of the river Nile.

In the Heliopolitan system of theology the god Osiris held a comparatively subordinate position in the paut, or company of the gods, and was in fact only the greatest of the gods of the dead who were worshipped in the Delta; in the “Book of that which is in the Underworld” he also holds a position subordinate to Rā, and his underworld is made to be a portion of the Ṭuat through which the dead sun passed nightly.

The Book of the Pylons

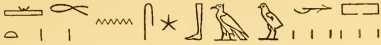

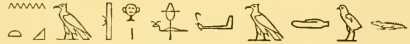

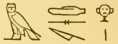

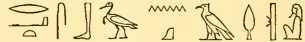

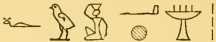

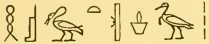

In the Shāt en Sbau, , or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort.

, or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort.

, or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort.

, or “Book of the Pylons,” the greatest god of all is the god Osiris, and the whole work is devoted to a description of the various sections of the region over which he presides, and is intended to form a guide to it whereby the souls of the dead may be enabled to make their way through it successfully and in comfort.

The Shāt ȧm Ṭuat and the Shāt en sbau were, in fact, the outcome of two distinct schools of theology; the latter, in its most primitive form, was the older of the two, and described the life of man after death more as a continuation of his existence on this earth than as an entirely new life, while the former made the future life to be passed entirely with the Sun-god.

The latter maintained the views about the Elysian Fields and their material delights, which found utterance in the “Book of Coming Forth by Day,” and was to all intents and purposes an amplification of, and a companion volume to it, but it also contained doctrines which were inserted in it with the view of making it harmonize with the theories in the former which related to the absolute supremacy of Rā.

The Theban priests had no wish, when once they had established the mastery of Ȧmen-Rā, but to bring all the doctrines of the various schools of religious thought into harmony with their own, for such a course could do nothing but contribute to the material prosperity of the great brotherhood of Amen-Rā. They were tolerably sure of the offerings of the faithful of Thebes, but they were anxious to obtain a share of those of the devotees of Osiris who flocked to Abydos, which was, rightly or wrongly, celebrated as the burial-place of the god.

The history of Egypt shows that the fight between the kings of the South and the kings of the North for the supremacy of the whole country was always going on, but as the fortunes of war had given victory to the kings of the South, who were the lords of all Egypt under the New Empire, the priests of the god of these kings determined that Ȧmen-Rā should be the king of the gods. Religious ambition was helped by the success of the great warrior kings of the XVIIIth Dynasty, and thus Ȧmen-Rā became the overlord of Osiris.

Divisions of the Underworld

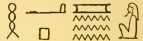

Both the “Book of that which is in the Underworld” and the “Book of the Pylons” divide the Ṭuat into twelve parts, each of which corresponds to one of the hours of the night, and the divisions are called

- “Field,”

, sekhet,

, sekhet, - or “City,”

, nut,

, nut, - or “Hall,”

, ārret,

, ārret, - or “Circle,”

, qerert.

, qerert.

In Chapter cxliv. of the Book of the Dead, according to the Papyrus of Nu (Brit. Mus.,No. 10,477), the Ārrets are seven in number, and each is guarded by a doorkeeper, a watcher, and a herald with the following names:—

Ārret I.

- Sekheṭ-ḥrȧ-āsht-ȧru,

.

. - Semetu,

.

. - Hu-kheru,

Ārret II.

- Ṭun-peḥti,

.

. - Seqeṭ-ḥrȧ,

.

. - Sabes,

.

.

Ārret III.

- Am-ḥuat-ent-peḥ-fi,

.

. - Res-ḥrȧ,

.

. - Uāau,

.

.

Arret IV.

- Khesef-ḥrȧ-āsh-kheru,

.

. - Res-ȧb,

.

. - Neteqa-ḥrȧ-khesef-aṭu,

Ārret V.

- Ānkh-em-fentu,

.

. - Ashebu,

.

. - Ṭeb-ḥer-kehaat,

Ārret VI.

- Ȧken-tau-k-ha-kheru,

.

. - Ȧn-ḥer,

.

. - Meṭes-ḥrȧ-ȧri-she,

Arret VII.

- Meṭes-sen,

.

. - Āa-kheru,

.

. - Khesef-ḥrȧ-khemiu,

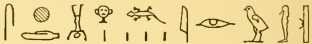

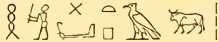

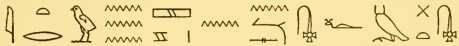

In Chapter cxlv. of the Book of the Lead according to the Theban and Saïte Recensions the domain of Osiris, i.e., Sekhet-Ȧarru,  , or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god.

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god.

, or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, or Sekhet-Ȧanre,

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god.

, contains Twenty-one pylons, each of which has a name, generally a very long one, and each of which is guarded by a god.

The names of the gods who guard the first ten of these pylons are:—

- Neri,

.

. - Mes-Peḥ,

.

. - Erṭāt-Sebanqa,

.

. - Neḳau,

.

. - Ḥenti-requ,

.

. - Semamti,

.

. - Ȧkenti,

.

. - Khu-tchet-f,

.

. - Tchesef,

.

. - Sekhen-ur,

.

.

These names are taken from the Papyrus of Nu already quoted (sheet 25), but the following come from the Turin Papyrus, Avhich was edited by Lepsius so far back as 1842, and they illustrate the changes which have taken place in the names.

- Nerȧu,

.

. - Mes-Ptaḥ,

.

. - Beq,

.

. - Ḥu-tepa,

.

. - Erṭā-ḥen-er-reqau,

.

. - Samti,

.

. - Ȧm-Nit,

.

. - Netchses,

.

. - Khau-tchet-f,

.

. - Sekhen-ur,

.

.

The names of all the pylons are given in both the Theban and Saïte Recensions, but the names of the gods who guard pylons XI.—XXI. are given in neither.

Divisions of Sekhet-ȧarru

The domain of Osiris, or Sekhet-Ȧarru, was, according to Chapters cxlix. and cl., divided into fifteen Ȧats, which are thus enumerated :—

- Ȧat (

) I. Sekhet Ȧarru; its god was Rā-Heru-khuti.

) I. Sekhet Ȧarru; its god was Rā-Heru-khuti. - Ȧat II. Ȧpt-ent-khet,

; its god was Fa-ākli,

; its god was Fa-ākli,  .

. - Ȧat III. Ṭu-qa-āat,

.

. - Ȧat IV. “The Ȧat of the spirits,”

.

. - Ȧat V. Ȧmmeḥet,

; the god in it is called Sekher-remu,

; the god in it is called Sekher-remu,  .

. - Ȧat VI. Ȧsset,

.

. - Ȧat VII. Ha-sert,

; the god in it is Fa-pet,

; the god in it is Fa-pet,  .

. - Ȧat VIII. Ȧpt-ent-qaḥu,

.

. - Ȧat IX. Ȧṭu,

; the god in it is Sepṭ,

; the god in it is Sepṭ,  .

. - Ȧat X. Unt,

; the god in it is Ḥetemet-baiu,

; the god in it is Ḥetemet-baiu,  .

. - Ȧat XI. Ȧpt-net,

; the god in it is Āa-sekhemu,

; the god in it is Āa-sekhemu,  .

. - Ȧat XII. Kher-āḥa,

; the god in it is Ḥāp,

; the god in it is Ḥāp,  i.e., the Nile.

i.e., the Nile. - Ȧat XIII. Ȧtru-she-en-nesert-f-em-shet,

.

. - Ȧat XIV. Ȧkesi,

; the god in it is Maa-thet-f,

; the god in it is Maa-thet-f,  .

. - Ȧat XV. Ȧmentet-nefert, “Beautiful Amentet,

,” wherein the gods live upon cakes and ale.

,” wherein the gods live upon cakes and ale.

In connexion with these various divisions of the realm of Osiris here will follow naturally a brief description of the Book of Pylons. An excellent copy of its text, with illustrations, is to be found on the famous alabaster sarcophagus of Seti I., now preserved in Sir John Soane’s Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and variants of several of the passages are given on the walls of the tombs of several kings of the XXth Dynasty, who were buried in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes.

Curiously enough, the work, as M. Jéquier has remarked, seems never to have become popular, and copies of it are only found in royal tombs ; it is generally admitted that it represents an attempt on the part of the Theban priests to adjust the cult of Rā to that of Osiris, and if this be so there is little to wonder at if it failed.

No comments:

Post a Comment