Chapter IX - Rā, The Sun-god, And His Forms

Rā is the name which was given by the Egyptians of the dynastic period to the god of the sun, who was regarded as the maker and creator of everything which we see in the visible world around us, and of the gods in heaven, as well as of heaven itself, and of the Ṭuat or underworld and the beings therein ; the original meaning of his name is unknown, but at one period of Egyptian history it seems to have been thought that the word rā indicated “operative and creative power,” and that as a proper name it represented in meaning something like “Creator,” this epithet being used much in the same way and with the same idea as we use the term when applied to God Almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth and of all things therein.

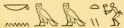

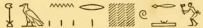

The worship of the sun in Egypt is extremely ancient and appears to have been universal; at a very early period adoration of him was associated with that of the hawk-god Ḥeru, who was the personification of the “height” of heaven, and who appears to have been a type and symbol of the sun. The worship of the hawk-god Ḥeru,

, is the oldest in Egypt, and, strictly speaking, he should have been discussed before Rā, but as Rā and the personifications of his various forms are the greatest of the gods of the Egyptians, he must be regarded as the true “father of the gods,” and his attributes, and the myths which grew up round him must be considered before those of Horus.

, is the oldest in Egypt, and, strictly speaking, he should have been discussed before Rā, but as Rā and the personifications of his various forms are the greatest of the gods of the Egyptians, he must be regarded as the true “father of the gods,” and his attributes, and the myths which grew up round him must be considered before those of Horus.

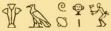

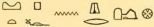

The god Rā is usually depicted with the body of a man and the head of a hawk, but sometimes he is represented in the form of a hawk ; on his head he wears his symbol,  , i.e., the disk of the sun encircled by the serpent khut,

, i.e., the disk of the sun encircled by the serpent khut,  , of which mention has already been made. When he has a human body he holds the emblem of life,

, of which mention has already been made. When he has a human body he holds the emblem of life,  , in his right hand, and a sceptre,

, in his right hand, and a sceptre,  , in his left, and from the belt of his tunic hangs down the tail, which is a survival of the dress of men in predynastic times, and probably later.

, in his left, and from the belt of his tunic hangs down the tail, which is a survival of the dress of men in predynastic times, and probably later.

, i.e., the disk of the sun encircled by the serpent khut,

, i.e., the disk of the sun encircled by the serpent khut,  , of which mention has already been made. When he has a human body he holds the emblem of life,

, of which mention has already been made. When he has a human body he holds the emblem of life,  , in his right hand, and a sceptre,

, in his right hand, and a sceptre,  , in his left, and from the belt of his tunic hangs down the tail, which is a survival of the dress of men in predynastic times, and probably later.

, in his left, and from the belt of his tunic hangs down the tail, which is a survival of the dress of men in predynastic times, and probably later.

Viewed from a practical point of view Rā was the oldest of all the gods of Egypt, and the first act of creation was the appearance of his disk above the waters of the world-ocean ; with his first rising time began, but no attempt was ever made to say when, i.e., how long ago, his first rising took place. When the Egyptians said that a certain thing had been in existence “since the time of Rā” it was equivalent to saying that it had existed for ever.

Boats of the Sun

The Egyptians, knowing that the sun was a fire, found a difficulty in assuming that it rose directly into the sky from out of the watery mass wherein it was brought forth, and they, therefore, assumed that it must make its journey over the waters in a boat, or boats, and as a matter of fact they believed that it passed over the first half of its course in one boat, and over the second half in another.

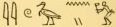

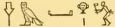

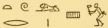

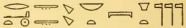

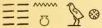

The morning boat of the sun was called Māṭet,  , i.e., “becoming strong” and the name of the evening boat was Semktet,

, i.e., “becoming strong” and the name of the evening boat was Semktet,  , i.e., “becoming weak”; these are appropriate names for the rising and the setting sun. The course which Rā followed in his journey across the sky was thought to have been defined at creation by the goddess called Maāt, who was the personification of the conceptions of rectitude, straightness, law, order, unfailing regularity, and the like, and there is no doubt that it was the regular and unfailing appearance of the sun each morning, as much as its light and heat, which struck wonder into primitive man, and made him worship the sun.

, i.e., “becoming weak”; these are appropriate names for the rising and the setting sun. The course which Rā followed in his journey across the sky was thought to have been defined at creation by the goddess called Maāt, who was the personification of the conceptions of rectitude, straightness, law, order, unfailing regularity, and the like, and there is no doubt that it was the regular and unfailing appearance of the sun each morning, as much as its light and heat, which struck wonder into primitive man, and made him worship the sun.

, i.e., “becoming strong” and the name of the evening boat was Semktet,

, i.e., “becoming strong” and the name of the evening boat was Semktet,  , i.e., “becoming weak”; these are appropriate names for the rising and the setting sun. The course which Rā followed in his journey across the sky was thought to have been defined at creation by the goddess called Maāt, who was the personification of the conceptions of rectitude, straightness, law, order, unfailing regularity, and the like, and there is no doubt that it was the regular and unfailing appearance of the sun each morning, as much as its light and heat, which struck wonder into primitive man, and made him worship the sun.

, i.e., “becoming weak”; these are appropriate names for the rising and the setting sun. The course which Rā followed in his journey across the sky was thought to have been defined at creation by the goddess called Maāt, who was the personification of the conceptions of rectitude, straightness, law, order, unfailing regularity, and the like, and there is no doubt that it was the regular and unfailing appearance of the sun each morning, as much as its light and heat, which struck wonder into primitive man, and made him worship the sun.

In passing through the Ṭuat, or underworld, at night Rā was supposed to be obliged to leave his boat at certain places, and to make use of others, including even one which was formed by the body of a serpent; according to one opinion he changed his boat every hour during the day and night, but the oldest belief of all assigned to him two boats only.

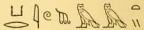

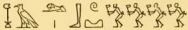

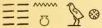

Rā was accompanied on his journey by a number of gods, whose duties consisted in navigating the boat, and in helping it to make a successful passage from the eastern part of the sky to the place where the god entered the Ṭuat; the course was set by Thoth and his female counterpart Maāt, and these stood one on each side of Horus, who acted as the steersman and apparently as captain also. Before the boatof Rā, one on each side, swam the two pilot fishes called Ȧbṭu,  , and Ȧnt,

, and Ȧnt,  , respectively. But, judging from the religious and mythological texts which have come down to us, not all the power of Rā himself, nor that of the gods who were with him, could ward off the attacks of certain fiends and monsters which endeavoured to obstruct the passage of his boat.

, respectively. But, judging from the religious and mythological texts which have come down to us, not all the power of Rā himself, nor that of the gods who were with him, could ward off the attacks of certain fiends and monsters which endeavoured to obstruct the passage of his boat.

, and Ȧnt,

, and Ȧnt,  , respectively. But, judging from the religious and mythological texts which have come down to us, not all the power of Rā himself, nor that of the gods who were with him, could ward off the attacks of certain fiends and monsters which endeavoured to obstruct the passage of his boat.

, respectively. But, judging from the religious and mythological texts which have come down to us, not all the power of Rā himself, nor that of the gods who were with him, could ward off the attacks of certain fiends and monsters which endeavoured to obstruct the passage of his boat.Mythological Fish

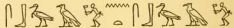

Chief among such were the serpent Āpep,  , and Sebȧu,

, and Sebȧu,  , and Nȧk,

, and Nȧk,  , and of these the greatest and most wicked was Āpep. In dynastic times Āpep was a personification of the darkness of the darkest hour of the night, against which Rā must not only fight, but fight successfully before he could rise in the east in the morning ; but originally he was the thick darkness which enveloped the watery abyss of Nu, and which formed such a serious obstacle to the sun when he was making his way out of the inert mass from which he proceeded to rise the first time. In the Book of the Dead he is frequently mentioned, but rather from a moral than a physical point of view.

, and of these the greatest and most wicked was Āpep. In dynastic times Āpep was a personification of the darkness of the darkest hour of the night, against which Rā must not only fight, but fight successfully before he could rise in the east in the morning ; but originally he was the thick darkness which enveloped the watery abyss of Nu, and which formed such a serious obstacle to the sun when he was making his way out of the inert mass from which he proceeded to rise the first time. In the Book of the Dead he is frequently mentioned, but rather from a moral than a physical point of view.

, and Sebȧu,

, and Sebȧu,  , and Nȧk,

, and Nȧk,  , and of these the greatest and most wicked was Āpep. In dynastic times Āpep was a personification of the darkness of the darkest hour of the night, against which Rā must not only fight, but fight successfully before he could rise in the east in the morning ; but originally he was the thick darkness which enveloped the watery abyss of Nu, and which formed such a serious obstacle to the sun when he was making his way out of the inert mass from which he proceeded to rise the first time. In the Book of the Dead he is frequently mentioned, but rather from a moral than a physical point of view.

, and of these the greatest and most wicked was Āpep. In dynastic times Āpep was a personification of the darkness of the darkest hour of the night, against which Rā must not only fight, but fight successfully before he could rise in the east in the morning ; but originally he was the thick darkness which enveloped the watery abyss of Nu, and which formed such a serious obstacle to the sun when he was making his way out of the inert mass from which he proceeded to rise the first time. In the Book of the Dead he is frequently mentioned, but rather from a moral than a physical point of view.

Thus in the xxxixth Chapter the deceased says:

“Get thee back, Fiend, before the darts of his beams. Rā hath overthrown thy words, the gods have turned thy face backwards, the Lynx (Mafṭet,), hath torn open thy breast, the Scorpion goddess,

, hath cast fetters upon thee, and Maāt hath sent forth thy destruction. Those who are in the ways have overthrown thee; fall down and depart, O Āpep, thou Enemy of Rā.”

A little further on the deceased says:

“I have brought fetters to thee, O Rā, and Āpep hath fallen because thou hast drawn them tight. The gods of the South, and of the North, of the West and of the East have fastened chains upon him, and they have fastened him with fetters; the god Rekes () hath overthrown him, and the god Ḥertit (

) hath put him in chains. O Āpep, thou Enemy of Rā, thou shalt never partake of the delights of love, thou shalt never fulfil thy desire ! He maketh thee to go back, O thou who art hateful to Rā ; he looketh upon thee, get thee back. He pierceth thy head, he slitteth up thy face, he divideth thy head where its bones join and it is crushed in thy land, thy bones are smashed in pieces, thy members are hacked off thee, and the god Aker (

) hath passed sentence of doom upon thee.”

Rā and Āpep

From the “Books of Overthrowing Āpep,” we obtain further information as to the destruction of the monster, and we find, that this work was recited daily in the temple of Ȧmen-Rā at Thebes.

The first Book was divided into Chapters, which were entitled:—

- Chapter of spitting upon Āpep.

- Chapter of defiling Āpep with the left foot.

- Chapter of taking a lance to smite Āpep.

- Chapter of fettering Āpep.

- Chapter of taking a knife to smite Āpep.

- Chapter of putting fire upon Āpep.

The following Books describe with great minuteness the details of the destruction which was to fall upon Āpep, and they are insisted on to a wearisome degree ; according to these the monster, which is referred to at one time as a crocodile and at another as a serpent, is first to be speared, then gashed with knives, and every bone of his body having been separated by red-hot knives, and his head, and legs, and tail, etc., having been cut off, his remains were to be scorched, and singed, and roasted, and finally shrivelled up and consumed by fire.

The same fate was to come upon Āpep’s confederates, and everything which formed parts of him and of them, i.e., their shadows, souls, doubles, and spirits, were to be wiped out of existence, including any offspring which they might possess.

Names of Āpep

Not content with reciting the words of power which would have the effect of destroying Āpep and his fiends, great care was taken to perform various ceremonies of a magical character, which were supposed to benefit not only Rā, but those who worshipped him on earth. Āpep was both crafty and evil-doing, and like Rā, lie possessed many names ; to destroy him it was necessary to curse him by each and every name by which he was known.

To make quite sure that this should be done effectively the Papyrus of Nesi-Ȧmsu adds a list of such names, and as they are the foundation of many of the magical names met with in later papyri they are here enumerated:—

- Neshṭ.

- Ṭuṭu.

- Ḥau-ḥrȧ.

- Hemhemti.

- Qeṭṭtu.

- Qerneru.

- Iubani.

- Āmam.

- Ḥem-taiu.

- Sȧaṭet-ta.

- Khermuti.

- Kenememti.

- Sheta.

- Serem-taui.

- Sekhem-ḥrȧ.

- Unti.

- Karȧu-ȧnementi.

- Khesef-ḥrȧ.

- Seba-ent-seba.

- Khak-ȧb.

- Khan-ru .... uāa.

- Nāi.

- Ām.

- Turrupa (?)

- Iubau.

- Uai.

- Kharubu, the four times wicked.

- Sau.

- Beṭeshu.

Rā and Āpep

In the Egyptian texts we have at present no account of the first fight which took place between Rā and Āpep, but it is clear from several passages in the “Books of Overthrowing Āpep” that such a thing must have occurred, and that the means employed by the Sun-god for destroying his foe resembled those made use of by Marduk in slaying Tiamat. The original of the Assyrian story is undoubtedly of Sumerian origin, and must be very old, and it is probable that both the Egyptians and the Sumerians derived their versions from a common source.

In the Assyrian version Marduk is armed with the invincible club which the gods gave him, and with a bow, spear, net, and dagger ; the lightning was before him, and fierce fire filled his body, and the four-fold wind and the seven-fold wind went with him. Marduk grasped the thunderbolt and then mounted his chariot, drawn by four swift and fiery horses which had been trained to beat down under their feet everything which came in their way. When he came to the place where Tiamat was, Kingu, whom she had set over her forces, trembled and was afraid, but Tiamat “stood firm with unbent neck.”

After an exchange of words of abuse the fight began, and Tiamat pronounced her spell, which, however, had no effect, for Marduk caught her in his net, and drove the winds which he had with him into her body, and whilst her belly was thus distended he thrust his spear into her, and stabbed her to the heart, and cut through her bowels, and crushed her skull with his club. On her body he took his stand, and with his knife he split it “like a flat fish into two halves,” and of one of these he made a covering for the heavens. With the exception of the last, every detail of the Assyrian account of the fight has its equivalent in the Egyptian texts which concern Rā and Āpepi.

An allusion to the fight is found in the apocryphal work of “Bel and the Dragon,” wherein we are told that both the god and the monster were worshipped in Babylon ; but the narrative says that the dragon was destroyed by means of lumps of pitch, and fat, and hair seethed together, and that these having been pushed into the creature’s mouth he burst asunder. In Egyptian papyri Āpep is always represented in the form of a serpent, in each undulation of which a knife is stuck,  ; in the “Book of the Gates” (see above p. 197) we see him fastened by the neck with a chain (along which is stretched the scorpion goddess Serqet), the end of which is in the hands of a god, and also chained to the ground by five chains.

; in the “Book of the Gates” (see above p. 197) we see him fastened by the neck with a chain (along which is stretched the scorpion goddess Serqet), the end of which is in the hands of a god, and also chained to the ground by five chains.

; in the “Book of the Gates” (see above p. 197) we see him fastened by the neck with a chain (along which is stretched the scorpion goddess Serqet), the end of which is in the hands of a god, and also chained to the ground by five chains.

; in the “Book of the Gates” (see above p. 197) we see him fastened by the neck with a chain (along which is stretched the scorpion goddess Serqet), the end of which is in the hands of a god, and also chained to the ground by five chains.

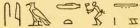

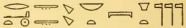

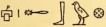

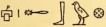

It has already been said that Rā was the “father of the gods,” and we find that as early as the Vth Dynasty a female counterpart, who was the mother of the gods, was assigned to him. This goddess is called in the text of Unȧs (1. 253) Rāt,  , and in later times her title appears to have been “Rāt of the two lands, the lady of heaven, mistress of the gods,”

, and in later times her title appears to have been “Rāt of the two lands, the lady of heaven, mistress of the gods,”  ; she is also called “Mistress of Heliopolis.” Her full name was, perhaps, Rāt-taiut,

; she is also called “Mistress of Heliopolis.” Her full name was, perhaps, Rāt-taiut,  , i.e., “Rāt of the world.” She is depicted in the form of a woman who wears on her head a disk with horns and a uraeus, and sometimes there are two feathers above the disk; the attributes of the goddess are unknown, but it is not likely that she was considered to be more important than any other great goddess.

, i.e., “Rāt of the world.” She is depicted in the form of a woman who wears on her head a disk with horns and a uraeus, and sometimes there are two feathers above the disk; the attributes of the goddess are unknown, but it is not likely that she was considered to be more important than any other great goddess.

, and in later times her title appears to have been “Rāt of the two lands, the lady of heaven, mistress of the gods,”

, and in later times her title appears to have been “Rāt of the two lands, the lady of heaven, mistress of the gods,”  ; she is also called “Mistress of Heliopolis.” Her full name was, perhaps, Rāt-taiut,

; she is also called “Mistress of Heliopolis.” Her full name was, perhaps, Rāt-taiut,  , i.e., “Rāt of the world.” She is depicted in the form of a woman who wears on her head a disk with horns and a uraeus, and sometimes there are two feathers above the disk; the attributes of the goddess are unknown, but it is not likely that she was considered to be more important than any other great goddess.

, i.e., “Rāt of the world.” She is depicted in the form of a woman who wears on her head a disk with horns and a uraeus, and sometimes there are two feathers above the disk; the attributes of the goddess are unknown, but it is not likely that she was considered to be more important than any other great goddess.The City of the Sun

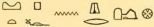

The home and centre of the worship of Rā in Egypt during dynastic times was the city called Ȧnnu,  , or An by the Egyptians, On by the Hebrews, and Heliopolis by the Greeks ; its site is marked by the village of Maṭarîyeh, which lies about five miles to the north-east of Cairo. It was generally known as Ȧnnu meḥt, i.e., Annu of the North, to distinguish it from Ȧnnu Qemāu, i.e., “Annu of the South,” or Hermonthis. Among the early Christians great store was set upon the oil made from the trees which grew there, and in the famous “Fountain of the Sun” the Virgin Mary is said to have washed the garments of her Son ; the ancient Egyptians also believed that Rā bathed each day at sunrise in a certain lake or pool which was in the neighbourhood.

, or An by the Egyptians, On by the Hebrews, and Heliopolis by the Greeks ; its site is marked by the village of Maṭarîyeh, which lies about five miles to the north-east of Cairo. It was generally known as Ȧnnu meḥt, i.e., Annu of the North, to distinguish it from Ȧnnu Qemāu, i.e., “Annu of the South,” or Hermonthis. Among the early Christians great store was set upon the oil made from the trees which grew there, and in the famous “Fountain of the Sun” the Virgin Mary is said to have washed the garments of her Son ; the ancient Egyptians also believed that Rā bathed each day at sunrise in a certain lake or pool which was in the neighbourhood.

, or An by the Egyptians, On by the Hebrews, and Heliopolis by the Greeks ; its site is marked by the village of Maṭarîyeh, which lies about five miles to the north-east of Cairo. It was generally known as Ȧnnu meḥt, i.e., Annu of the North, to distinguish it from Ȧnnu Qemāu, i.e., “Annu of the South,” or Hermonthis. Among the early Christians great store was set upon the oil made from the trees which grew there, and in the famous “Fountain of the Sun” the Virgin Mary is said to have washed the garments of her Son ; the ancient Egyptians also believed that Rā bathed each day at sunrise in a certain lake or pool which was in the neighbourhood.

, or An by the Egyptians, On by the Hebrews, and Heliopolis by the Greeks ; its site is marked by the village of Maṭarîyeh, which lies about five miles to the north-east of Cairo. It was generally known as Ȧnnu meḥt, i.e., Annu of the North, to distinguish it from Ȧnnu Qemāu, i.e., “Annu of the South,” or Hermonthis. Among the early Christians great store was set upon the oil made from the trees which grew there, and in the famous “Fountain of the Sun” the Virgin Mary is said to have washed the garments of her Son ; the ancient Egyptians also believed that Rā bathed each day at sunrise in a certain lake or pool which was in the neighbourhood.

Of the origin and beginnings of the worship of Rā at Heliopolis we know nothing, but it is quite certain that under the Vth Dynasty, about ii.c. 3350, the priests of Rā had settled themselves there, and that they had obtained great power at that remote period. The evidence derived from the Westcar Papyrus indicates that User-ka-f, the first king of the Vth Dynasty, was the high-priest of Rā, and that he was the first to add “son of the Sun” to the titles of Egyptian monarchs.

Up to that time a king seems to have possessed :—

- A name as the descendant or servant of Horus.

- A name as the descendant or servant of Set.

- A name as lord of the shrines of Nekhebet and Uatchit,

.

. - A name as king of the North and South,

.

.

User-ka-f, however, introduced the title of “son of the Sun,”  , which was always followed by a second cartouche, and it was adopted by every succeeding king of Egypt. According to the Westcar Papyrus User-ka-f and his two immediate successors Sahu-Rā and Kakaȧ were the sons of the god Rā by Ruṭ-ṭeṭeṭ, the wife of a priest of the god Rā of Sakhabu,

, which was always followed by a second cartouche, and it was adopted by every succeeding king of Egypt. According to the Westcar Papyrus User-ka-f and his two immediate successors Sahu-Rā and Kakaȧ were the sons of the god Rā by Ruṭ-ṭeṭeṭ, the wife of a priest of the god Rā of Sakhabu,  ; these were brought into the world by the

; these were brought into the world by the

, which was always followed by a second cartouche, and it was adopted by every succeeding king of Egypt. According to the Westcar Papyrus User-ka-f and his two immediate successors Sahu-Rā and Kakaȧ were the sons of the god Rā by Ruṭ-ṭeṭeṭ, the wife of a priest of the god Rā of Sakhabu,

, which was always followed by a second cartouche, and it was adopted by every succeeding king of Egypt. According to the Westcar Papyrus User-ka-f and his two immediate successors Sahu-Rā and Kakaȧ were the sons of the god Rā by Ruṭ-ṭeṭeṭ, the wife of a priest of the god Rā of Sakhabu,  ; these were brought into the world by the

; these were brought into the world by the

goddesses Isis, Nephthys, Meskhenet, and Ḥeqet, and by the god Khnemu, and it was decreed by them that the three boys should be sovereigns of Egypt.

Rā Worship

This legend is of importance, not only as showing the order of the succession of the first three kings of the Vth Dynasty, but also because it proves that in the early Empire the kings of Egypt believed themselves to be the sons of Rā, the Sun-god. All chronological tradition affirms that Rā had once ruled over Egypt, and it is a remarkable fact that every possessor of the throne of Egypt was proved by some means or other to have the blood of Rā flowing in his veins, or to hold it because he was connected with Rā by marriage.

The bas-reliefs of Queen Ḥātshepset at Dêr al-Baḥarî, and those of Ȧmen-ḥetep III. at Luxor, and those of Cleopatra VII. in the temple at Erment (now destroyed, alas!) describe the process by which Rā or Ȧmen-Rā became the father of the kings and queens of Egypt. From these we see that whenever the divine blood needed replenishing the god took upon himself the form of the reigning king of Egypt, and that he visited the queen in her chamber and became the actual father of the child who was subsequently born to her.

When the child was born it was regarded as a god incarnate, and in due course was presented, with appropriate ceremonies, to Rā or Ȧmen-Rā, in his temple, and this god accepted it and acknowledged it to be his child. This clever priestly device gave the priests of Rā great power in the land, but their theocratic rule was not always the best for Egypt, and on one occasion they brought about the downfall of a dynasty. The first rise to power of the priests of Rā took place at the beginning of the Vth Dynasty, when the cult of Rā became dominant in the land. About the time of Userkaf we find that a number of shrines, which united the chief characteristics of the low rectangular tomb commonly known by its Arabic name of

masṭaba, i.e., “bench,” and of the pyramid, , were built in honour of the god; but, according to Prof. Sethe, the custom of building such only lasted for about one hundred years, i.e., from the reign of Userkaf to that of Men-kau-Ḥeru. Be this as it may, the priesthood of Heliopolis succeeded in making their worship of Rā to supersede generally that of almost every other god of Egypt, and in absorbing all the local gods of importance throughout the country into their theological system, wherein they gave them positions subordinate to those of Rā and his company of gods.

, were built in honour of the god; but, according to Prof. Sethe, the custom of building such only lasted for about one hundred years, i.e., from the reign of Userkaf to that of Men-kau-Ḥeru. Be this as it may, the priesthood of Heliopolis succeeded in making their worship of Rā to supersede generally that of almost every other god of Egypt, and in absorbing all the local gods of importance throughout the country into their theological system, wherein they gave them positions subordinate to those of Rā and his company of gods.

, were built in honour of the god; but, according to Prof. Sethe, the custom of building such only lasted for about one hundred years, i.e., from the reign of Userkaf to that of Men-kau-Ḥeru. Be this as it may, the priesthood of Heliopolis succeeded in making their worship of Rā to supersede generally that of almost every other god of Egypt, and in absorbing all the local gods of importance throughout the country into their theological system, wherein they gave them positions subordinate to those of Rā and his company of gods.

, were built in honour of the god; but, according to Prof. Sethe, the custom of building such only lasted for about one hundred years, i.e., from the reign of Userkaf to that of Men-kau-Ḥeru. Be this as it may, the priesthood of Heliopolis succeeded in making their worship of Rā to supersede generally that of almost every other god of Egypt, and in absorbing all the local gods of importance throughout the country into their theological system, wherein they gave them positions subordinate to those of Rā and his company of gods.Rā and Rā-tem

Originally the local god of the city was Tem, who was worshipped there in a special temple, but they united his attributes to those of Rā and formed the double god Rā-Tem, (Unȧs, 1. 222). With the close of the VIth Dynasty the power of the priests of Rā declined, and it was not until the reign of Usertsen I., about B.C. 2433, that the sanctuary at Heliopolis was rebuilt, or perhaps entirely refounded. This king dedicated the temple which he built there to Rā and to two forms of this god, Horus and Temu, who were supposed to be incarnate in the famous Bull of Mnevis, which was worshipped at Heliopolis as Apis was worshipped at Memphis.

(Unȧs, 1. 222). With the close of the VIth Dynasty the power of the priests of Rā declined, and it was not until the reign of Usertsen I., about B.C. 2433, that the sanctuary at Heliopolis was rebuilt, or perhaps entirely refounded. This king dedicated the temple which he built there to Rā and to two forms of this god, Horus and Temu, who were supposed to be incarnate in the famous Bull of Mnevis, which was worshipped at Heliopolis as Apis was worshipped at Memphis.

(Unȧs, 1. 222). With the close of the VIth Dynasty the power of the priests of Rā declined, and it was not until the reign of Usertsen I., about B.C. 2433, that the sanctuary at Heliopolis was rebuilt, or perhaps entirely refounded. This king dedicated the temple which he built there to Rā and to two forms of this god, Horus and Temu, who were supposed to be incarnate in the famous Bull of Mnevis, which was worshipped at Heliopolis as Apis was worshipped at Memphis.

(Unȧs, 1. 222). With the close of the VIth Dynasty the power of the priests of Rā declined, and it was not until the reign of Usertsen I., about B.C. 2433, that the sanctuary at Heliopolis was rebuilt, or perhaps entirely refounded. This king dedicated the temple which he built there to Rā and to two forms of this god, Horus and Temu, who were supposed to be incarnate in the famous Bull of Mnevis, which was worshipped at Heliopolis as Apis was worshipped at Memphis.

In front of the temple he set up two massive granite obelisks, each 66 feet high, the pyramidions of which were covered with copper ; these were still in situ about A.D. 1200. Between the XIIth and the XXth Dynasties we hear little of Heliopolis, but a further restoration of the temple buildings took place under Rameses III., who set apart large revenues for the maintenance of the worship of Rā and the dignity of his priests and servants.

When Piānkhi invaded Egypt, about B.C. 750, he visited Heliopolis after the capture of Memphis, going by way of the mountain of Kher-āḥa,  , and he performed certain ceremonial ablutions in the “Lake of cold water,”

, and he performed certain ceremonial ablutions in the “Lake of cold water,”  , and washed his face in the “milk of Nu wherein Rā was wont to wash his face;” this “Lake” is clearly the fountain of the sun which we have already mentioned.

, and washed his face in the “milk of Nu wherein Rā was wont to wash his face;” this “Lake” is clearly the fountain of the sun which we have already mentioned.

, and he performed certain ceremonial ablutions in the “Lake of cold water,”

, and he performed certain ceremonial ablutions in the “Lake of cold water,”  , and washed his face in the “milk of Nu wherein Rā was wont to wash his face;” this “Lake” is clearly the fountain of the sun which we have already mentioned.

, and washed his face in the “milk of Nu wherein Rā was wont to wash his face;” this “Lake” is clearly the fountain of the sun which we have already mentioned.Heliopolis

At a place called Shāi-qa-em-Ȧnnu he

“made great offerings at Shā-qa-em-Ȧmen to Rā at sunrise, viz., white oxen, milk, ānti unguent, incense, and sweet-smelling woods, and then he passed into the temple of Rā, which he entered bowing low in adoration to the god. The chief kher ḥeb priest,, offered up prayer on behalf of the king, that he might be able to repulse his enemies, and then having performed the ceremony connected with the ‘Star-room,’

, he took the seṭeb girdle, and purified himself with incense, and poured out a libation, when one brought to him the flowers which are offered up in the Ḥet-Benbenet,

. He took the flowers and went up the steps [leading to] the ‘great tabernacle,’

, to see Rā in Ḥet-Benbenet. He stood [on the top] there by himself, he pushed back the bolt, he opened the doors [of the tabernacle], and he saw his father Rā in Ḥet-Benbenet. He made adoration to the Māṭet Boat of Rā (i.e., the boat of the rising sun), and to the Sektet boat of Tem (i.e., the boat of the setting sun).

He then drew close the doors again, and having affixed thereto the clay for a seal he stamped it with the seal of the king himself. He then admonished the priests [saying],‘I have set [my] seal here, let no other king enter herein [or] stand here.’And they cast themselves on their bellies before his majesty, saying,‘May Horus who loveth Ȧnnu (Heliopolis) be firm and stable, and may he never come to an end.’

From the above it is certain that the sacred boats of Rā were kept in a sort of wooden tabernacle with two doors,  , that could be fastened by a bolt, and from what we know from pictures of these boats it is equally certain that the Māṭet boat contained a hawk-headed figure of Rā, and that the Sektet boat contained a man-headed figure of Rā. The text says that the tabernacle,

, that could be fastened by a bolt, and from what we know from pictures of these boats it is equally certain that the Māṭet boat contained a hawk-headed figure of Rā, and that the Sektet boat contained a man-headed figure of Rā. The text says that the tabernacle,  , was situated on the top of a flight of steps, and this is what we should expect, for we know that the support was intended to represent the high ground in or near the city of Khemennu,

, was situated on the top of a flight of steps, and this is what we should expect, for we know that the support was intended to represent the high ground in or near the city of Khemennu,  (Hermopolis), whereon Rā established himself on the day when he proceeded from the watery abyss of Nu, before the pillars of Shu were set up.

(Hermopolis), whereon Rā established himself on the day when he proceeded from the watery abyss of Nu, before the pillars of Shu were set up.

, that could be fastened by a bolt, and from what we know from pictures of these boats it is equally certain that the Māṭet boat contained a hawk-headed figure of Rā, and that the Sektet boat contained a man-headed figure of Rā. The text says that the tabernacle,

, that could be fastened by a bolt, and from what we know from pictures of these boats it is equally certain that the Māṭet boat contained a hawk-headed figure of Rā, and that the Sektet boat contained a man-headed figure of Rā. The text says that the tabernacle,  , was situated on the top of a flight of steps, and this is what we should expect, for we know that the support was intended to represent the high ground in or near the city of Khemennu,

, was situated on the top of a flight of steps, and this is what we should expect, for we know that the support was intended to represent the high ground in or near the city of Khemennu,  (Hermopolis), whereon Rā established himself on the day when he proceeded from the watery abyss of Nu, before the pillars of Shu were set up.

(Hermopolis), whereon Rā established himself on the day when he proceeded from the watery abyss of Nu, before the pillars of Shu were set up.

In the Book of the Dead this high ground is called “Qaqa in Khemennu,”

. During the period of the Persian invasion the prosperity of the priesthood of Heliopolis declined, and it is said that later, during the reign of Ptolemy II. (b.c. 285-247) many of its members found an asylum at Alexandria, where their reputation for learning caused them to be welcomed.

. During the period of the Persian invasion the prosperity of the priesthood of Heliopolis declined, and it is said that later, during the reign of Ptolemy II. (b.c. 285-247) many of its members found an asylum at Alexandria, where their reputation for learning caused them to be welcomed.

. During the period of the Persian invasion the prosperity of the priesthood of Heliopolis declined, and it is said that later, during the reign of Ptolemy II. (b.c. 285-247) many of its members found an asylum at Alexandria, where their reputation for learning caused them to be welcomed.

. During the period of the Persian invasion the prosperity of the priesthood of Heliopolis declined, and it is said that later, during the reign of Ptolemy II. (b.c. 285-247) many of its members found an asylum at Alexandria, where their reputation for learning caused them to be welcomed.

A tradition says Solon, Thales, and Plato all visited the great college at Heliopolis, and that the last-named actually studied there, and that Manetho, the priest of Sebennytus, who wrote a history of Egypt in Greek for Ptolemy II., collected his materials in the library of the priesthood of Rā. Some time, however, before the Christian era, the temple buildings were in ruins, and the glory of Heliopolis had departed, and it was frequented only by those who went there to carry away stone or anything else which would be useful in building or farming operations.

Cult of Heliopolis

We have now to consider briefly what was the nature of the doctrine which was the distinguishing characteristic of the teaching of the priests of Heliopolis. In the first place it proclaimed the absolute sovereignty of Rā among the gods, and it made him the head of every company of the gods, but it did not deny divinity to the older deities of the country.

The chief authorities for the Heliopolitan doctrine are the Pyramid Texts, to which allusion has so often been made, and from these we see that the priests of Rā displayed great ingenuity and tact in absorbing into their form of religion all the older cults of Egypt, together with their magical rites and ceremonies. Apparently they did not attempt to abolish the old, indigenous gods; on the contrary, they allowed their cults to be continued, provided that the local priesthoods would make their gods subordinate to Rā. Thus Osiris and Isis, and their companion gods, were absorbed into the great company of the gods of Heliopolis, and the theological system of the priests of Osiris was mixed with that of the priests of Rā.

Nothing is known of the origin of Osiris worship, but the god himself and the ceremonies which accompanied the celebration of his festivals suggest that he was known to the predynastic dwellers in Egypt. The belief in the efficacy of worship of the Man-god, who rose from the dead, and established himself in the underworld as judge and king, was indelibly impressed on the minds of the Egyptians at a very early period, and although the idea of a heaven of material delights which was promised to the followers of Osiris did not, probably, commend itself in all particulars to the imaginations of the refined and cultured folk of Egypt, it was tacitly accepted as true and was regarded as a portion of their religious inheritance by the majority of the people.

On the other hand, the priests of Rā declared that the souls of the blessed made their way after death to the boat of Rā, and that if they succeeded in alighting upon it their eternal happiness was assured. No fiends could vex and no foes assail them successfully, so long as they had their seat in the “Boat of Millions of Years;” they lived upon the food on which the gods lived, and that food was light.

They were apparelled in light, and they were embraced by the god of light. They passed with Rā in his boat through all the dangers of the Ṭuat, and when the god rose each morning they were free to wander about in heaven or to visit their old familiar habitations on earth, always however taking care to resume their places in the boat before nightfall, at which time evil spirits had great power to injure, and perhaps even to slay, the souls of those who had failed to arrive safely in the boat.

But although the priests of Rā under the Early Empire, and the priests of Ȧmen-Rā under the Middle and New Empires, were supported by all the power and authority of the greatest kings and queens who ever sat upon the throne of Egypt, in their proclamation of a heaven, which was of a far more spiritual character than that of Osiris, they never succeeded in obliterating the belief in Osiris from the minds of the great bulk of the population in Egypt. The material side of the Egyptian character refused to be weaned from the idea of a Field of Peace, which was situated near the Field of Reeds and the Field of the Grasshoppers, where wheat and barley grew in abundance, and where a man would possess a vine, and fig trees, and date palms, and be waited upon by his father and his mother, and where he would enjoy an existence more comfortable than that which he led upon this earth.

The doctrine of a realm of light, where the meat, and drink, and raiment were light, and the idea of becoming a being of light, and of passing eternity among creatures of light did not satisfy him. The result of all this was to create a perpetual contest between the two great priesthoods of Egypt, namely, those of Rā and Osiris ; in the end the doctrine of Osiris prevailed, and the attributes of the Sun-god were ascribed to him. In considering the struggle which went on between the followers of Rā and Osiris it is difficult not to think that there was some strong reason for the resistance which the priests of Rā met with from the Egyptians generally, and it seems as if the doctrine of Rā contained something which was entirely foreign to the ideas of the people.

The city of Heliopolis appears always to have contained a mixed population, and its situation made it a very convenient halting-place for travellers passing from Arabia and Syria into Egypt and vice versâ; it is, then, most probable that the doctrine of Rā as taught by the priests of Heliopolis was a mixture of Egyptian and Western Asiatic doctrines, and that it was the Asiatic element in it which the Egyptians resisted. It could not have been sun-worship which they disliked, for they had been sun-worshippers from time immemorial.

Tem of Heliopolis

Tem, or Temu, or Ȧtem, was originally the local god of the city of Ȧnnu, or Heliopolis, and in the dynastic period at all events he was held to be one of the forms of the great Sun-god Rā, and to be the personification of the setting sun. In the predynastic period, however, he was, as M. Lefébure has pointed out, the first man among the Egyptians who was believed to have become divine, and who was at his death identified with the setting sun; in other words, Tem was the first living man-god known to the Egyptians, just as Osiris was the first dead man-god, and as such was always represented in human form and with a human head.

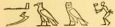

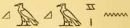

It is important to note this fact, for it indicates that those who formulated the existence of this god were on a higher level of civilization than those who depicted the oldest of all Egyptian gods, Horus, in the form of a hawk, or in that of a hawk-headed human body. In the papyri and on the monuments he usually wears , the crowns of the South and North, upon his head, and he holds

, the crowns of the South and North, upon his head, and he holds , the emblem of life, in his right hand, and the sceptre, (PLAATJE), in his left. In the boat of Rā he is depicted in human form even when Rā is symbolized by a disk which is being rolled along by a beetle, and the god Kheperȧ is represented by a beetle, and the rising sun Ḥeru-Khuti is shown under the form of a hawk’s head, from which fall rays of light.

, the emblem of life, in his right hand, and the sceptre, (PLAATJE), in his left. In the boat of Rā he is depicted in human form even when Rā is symbolized by a disk which is being rolled along by a beetle, and the god Kheperȧ is represented by a beetle, and the rising sun Ḥeru-Khuti is shown under the form of a hawk’s head, from which fall rays of light.

, the crowns of the South and North, upon his head, and he holds

, the crowns of the South and North, upon his head, and he holds , the emblem of life, in his right hand, and the sceptre, (PLAATJE), in his left. In the boat of Rā he is depicted in human form even when Rā is symbolized by a disk which is being rolled along by a beetle, and the god Kheperȧ is represented by a beetle, and the rising sun Ḥeru-Khuti is shown under the form of a hawk’s head, from which fall rays of light.

, the emblem of life, in his right hand, and the sceptre, (PLAATJE), in his left. In the boat of Rā he is depicted in human form even when Rā is symbolized by a disk which is being rolled along by a beetle, and the god Kheperȧ is represented by a beetle, and the rising sun Ḥeru-Khuti is shown under the form of a hawk’s head, from which fall rays of light.Rā-tem of Heliopolis

Tem was, in fact, to the Egyptians a manifestation of God in human form, and his conception in their minds marks the end of the period wherein they assigned animal forms to their gods, and the beginning of that in which they evolved the idea of God, almighty, inscrutable, unknowable, the maker and creator of the universe. It is useless to attempt to assign a date to the period when the Egyptians began to worship God in human form, for we have no material for doing so ; the worship of Tem must, however, be of very great antiquity, and the fact that the priests of Rā in the Vth and VIth Dynasties united him to their god under the name of Rā-Tem, , proves that his worship was wide-spread, and that the god was thought to possess attributes similar to those of Rā.

, proves that his worship was wide-spread, and that the god was thought to possess attributes similar to those of Rā.

, proves that his worship was wide-spread, and that the god was thought to possess attributes similar to those of Rā.

, proves that his worship was wide-spread, and that the god was thought to possess attributes similar to those of Rā.

The Pyramid Texts show that the attributes of Temu were confounded with those of Rā, and that the protection and favour of this god were all essential for the well-being of the deceased in the Underworld ; indeed, it is Tem the father who stretches out his hand to Pepi I. and sets him at the head of the gods, where he judges the great and the wise. This passage shows that Tem was regarded as the father of the human race, and as he was also divine his powers to help the dead were very great.

In many respects he was held to be the equal of Rā, and the prayers and hymns which were addressed to him frequently show that the Egyptians were very anxious to propitiate him. This is not difficult to understand if we remember the dogmas of the Heliopolitan priesthood about the means by which the souls of the blessed departed from this world.

They taught that souls when they left this world went to the region which lay between the earth and the beginning of the Valley of the Ṭuat, and which was called Ȧmentet, and that they waited there until the Boat of the Setting Sun, i.e., the boat of Rā in his form of Temu, made his appearance there ; as soon as it arrived the souls flocked to it, and those who had served Rā upon earth and whose bodies had been buried with the orthodox rites, and ceremonies, and prayers of the priesthood of Rā, and were, therefore, provided with the necessary words of power, were admitted to the boat of Tem, where they enjoyed the protection and favour of the god in his various forms to all eternity.

There was, moreover, another aspect of Tem which gave the god a position of peculiar importance in the minds of the Egyptians, i.e., he was identified not only with the god of the dead, Osiris, but also with the young Horus, the new and rising sun of the morrow. All these ideas are well expressed in a hymn to Tem which is found in the Papyrus of Mut-ḥetep (Brit. Mus., No. 10,010, sheet 5), and which was composed to enable every spirit who recited it to “come forth by day” and in any form he pleased and to have great power in the Ṭuat.

The lady Mut-ḥetep says,

“O Rā-Tem, in thy splendid progress thou risest, and thou settest as a living being in the glories of the western horizon; thou settest in thy territory which is in the Mount of Sunset (Manu,). Thy uraeus is behind thee, thy uraeus is behind thee. Homage to thee, O thou who art in peace ; homage to thee, O thou who art in peace. Thou art joined unto the Eye of Tem, and it chooseth its powers of protection [to place] behind thy members.

Thou goest forth through heaven, thou travellest over the earth, and thou jonrneyest onward. O Luminary, the northern and southern halves of heaven come to thee, and they bow low in adoration, and they do homage unto thee, day by day. The gods of Ȧmentet rejoice in thy beauties, and the unseen places sing hymns of praise unto thee.Those who dwell in the Sektet boat go round about thee, and the Souls of the East do homage to thee, and when they meet thy Majesty they cry: ‘Come, come in peace!’ There is a shout of welcome to thee, O lord of heaven and governor of Ȧmentet! Thou art acknowledged by Isis who seeth her son in thee, the lord of fear, the mighty one of terror.Thou settest as a living being in the hidden place. Thy father [Ta-]tunen raiseth thee up and he placeth both his hands behind thee; thou becomest endowed with divine attributes in [thy] members of earth; thou wakest in peace and thou settest in Manu. Grant thou that I may become a being honoured before Osiris, and that I may come to thee, O Rā-Tem ! I have adored thee, therefore do thou for me that which I wish. Grant thou that I may be victorious in the presence of the company of the gods.Thou art beautiful, O Rā, in thy western horizon of Ámentet, thou lord of Maāt, thou being who art greatly feared, and whose attributes are majestic, O thou who art greatly beloved by those who dwell in the Ṭuat! Thou shinest with thy beams upon the beings that are therein perpetually, and thou sendest forth thy light upon the path of Re-stau.Thou openest up the path of the double Lion-god, thou settest the gods upon [their] thrones, and the spirits in their abiding-places. The heart of Naȧrerf (i.e., Ȧn-ruṭ-f, a region of the Underworld) is glad [when] Rā setteth ; the heart of Naȧrerf is glad when Rā setteth.Hail, O ye gods of the land of Ȧmentet who make offerings and oblations unto Rā-Tem, ascribe ye glory [unto him when] ye meet him. Grasp ye your weapons and overthrow ye the fiend Sebȧ on behalf of Rā, and repulse the fiend Nebṭ on behalf of Osiris.The gods of the land of Ȧmentet rejoice and lay hold upon the cords of the Sektet boat, and they come in peace; the gods of the hidden place who dwell in Ȧmentet triumph.”

In the opening words of another hymn Tem is addressed as

“Rā, who in thy setting art Tem-Ḥeru-khuti (Tem-Harmachis), thou divine god, thou self-created being, thou primeval matter,”

from which we see that the attributes of selfcreation, etc., which, strictly speaking, belonged to Kheperȧ, were ascribed to Tem.

No comments:

Post a Comment