The texts in the pyramids of Unȧs and Tetȧ and their immediate successors prove that the religious literature of the Egyptians contains a multitude of beliefs and opinions which belong to all periods of their history, and represent different stages in the development of their civilization. Their ideas about the various parts which constitute their material, and mental, and spiritual existences cannot have been conceived all at once, but it is very hard to say in respect of some of them which came first.

We need not trouble about the order of the development of their ideas about the constituent parts of the gods, for in the earliest times, at least, the Egyptians only ascribed to them the attributes which they had already ascribed to themselves; once having believed that they possessed doubles, shadows, souls, spirits, hearts, (i.e., the seats of the mental life), names, powers, and spiritual bodies, they assigned the like to the gods. But if the gods possessed doubles, and shadows, and hearts, none of which, in the case of man, can exist without bodies, they too must possess bodies, and thus the Egyptians conceived the existence of gods who could eat, and drink, and love, and hate, and fight, and make war, and grow old, and die, and perish as far as their bodies were concerned.

And although the texts show that in very early times they began to conceive monotheistic ideas, and to develop beliefs of a highly spiritual character, the Egyptians never succeeded in abandoning the crude opinion about the gods which their indigenous ancestors had formed long before the dynastic period of their history. It is, of course, impossible to assume that educated classes of Egypt held such opinions, notwithstanding the fact that religious texts which were written for their benefit contain as great a mixture of views and beliefs of all periods as those which were written for humbler folk.

Beliefs In Immortality

The Book of the Dead in all dynasties proves that the rich and the poor, and the educated and the uneducated alike prayed for funeral offerings in the very Chapters in which they proclaimed their sure belief in an existence in which material things were superfluities. In the texts of the Early Empire the deceased is declared to be a god, or God, and the son of god, or God, and the oldest god of all, Horus, gives him his eye, and he sits on a great throne by the side of God ; yet in the same texts we read that he partakes of the figs and wine of the gods, that he drinks beer which lasts for ever, that he thirsts not like the gods Shu and Tefnut, and that the throne of God is made of iron, that its legs terminate in hoofs like those of bulls, and that its sides are ornamented with the faces of lions.

The great god Horus gives him his own “double” (ha), and yet there are in heaven enemies who dare to oppose the deceased; and although he is declared to be immortal, “all the gods give him of their food that he may not die,” and he sits down, clothed in white linen and wearing white sandals, with the gods by the lake in the Field of Peace, and partakes with them of the wood (or, tree) of life on which they themselves live that he also may live.

Though he is the son of God he is also the child of Sothis, and the brother of the Moon, and the goddess Isis becomes his wife ; though he is the son of God we are also told that his flesh and his bones have been gathered together, that his material body has been reconstructed ; that his limbs perform all the functions of a healthy body; and as he lives as the gods live we see that from one point of view he and the o:ods are constituted alike.

Instances of the mixture of spiritual with material ideas might be multiplied almost indefinitely, and numbers of passages containing the most contradictory statements might be adduced almost indefinitely to prove that the ideas of the Egyptians about the world beyond the grave, and about God and the gods were of a savage, childish, and inconsistent character. What, however, we have to remember in dealing with Egyptian religious texts is that the innate conservatism of the Egyptian in all ages never permitted him to relinquish any belief which had once found expression in writing, and that the written word was regarded by him as a sacred thing which, whether he believed it not, must be copied and preserved with great care, and if possible without any omission or addition whatsoever.

Thus religious ideas and beliefs which had been entirely forgotten by the people of Egypt generally were preserved and handed down for thousands of years by the scribes in the temples. The matter would have been simple enough if they had done this and nothing more, but unfortunately they incorporated new texts into the collections of old ones, and the various attempts which the priests and scribes made to harmonize them resulted in the confusion of beliefs which we now have in Egyptian religious works.

Composite Animal-gods

Before we pass to the consideration of the meaning of the old Egyptian name for god and God, i.e., “neter,” mention must be made of a class of beings which were supposed to possess bodies partly animal and partly human, or were of a composite character.

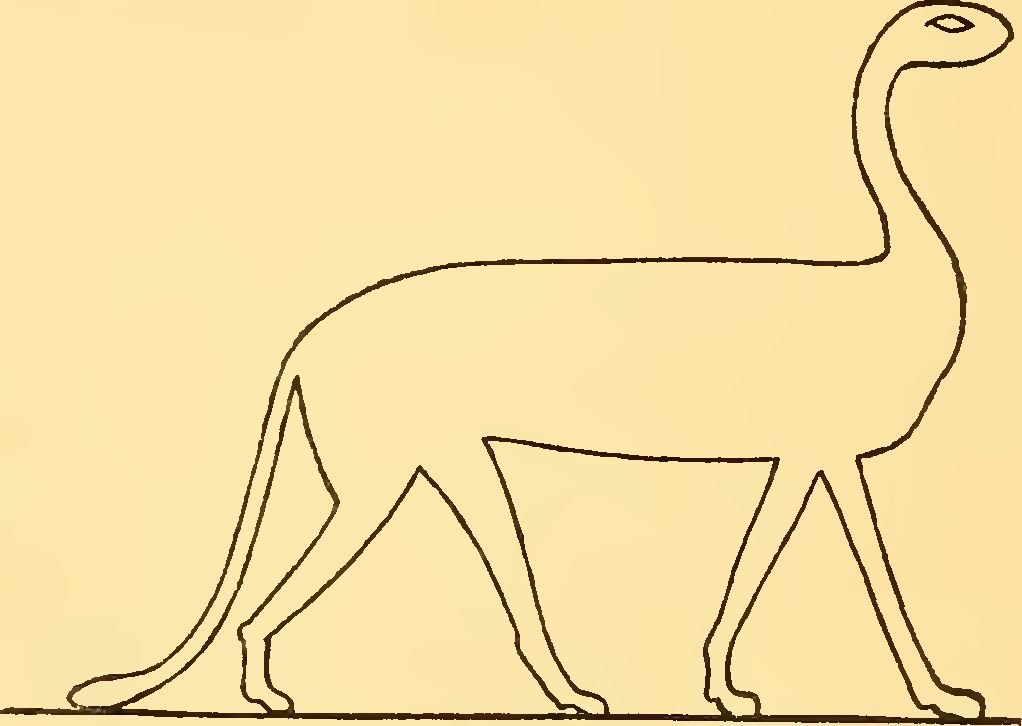

Image right 1: The serpent-headed leopard Setcha.

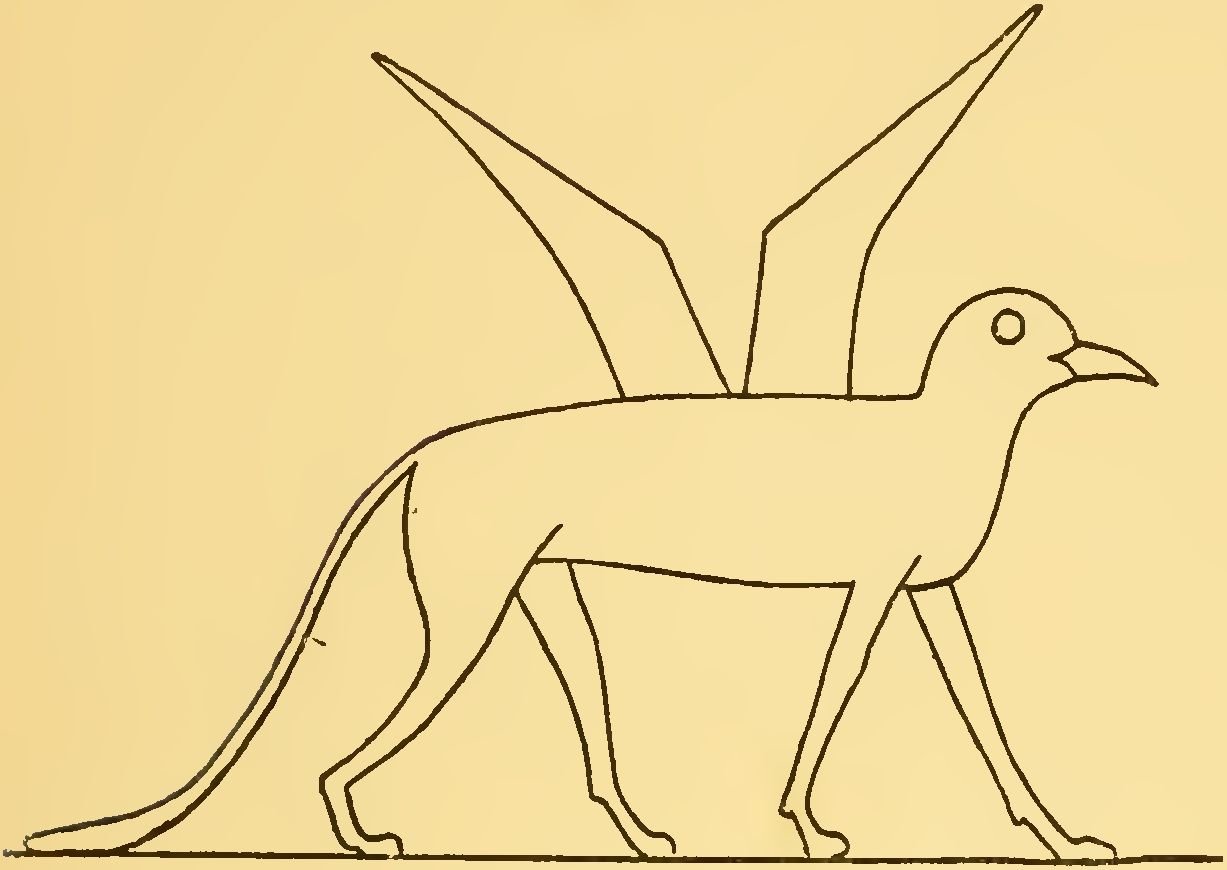

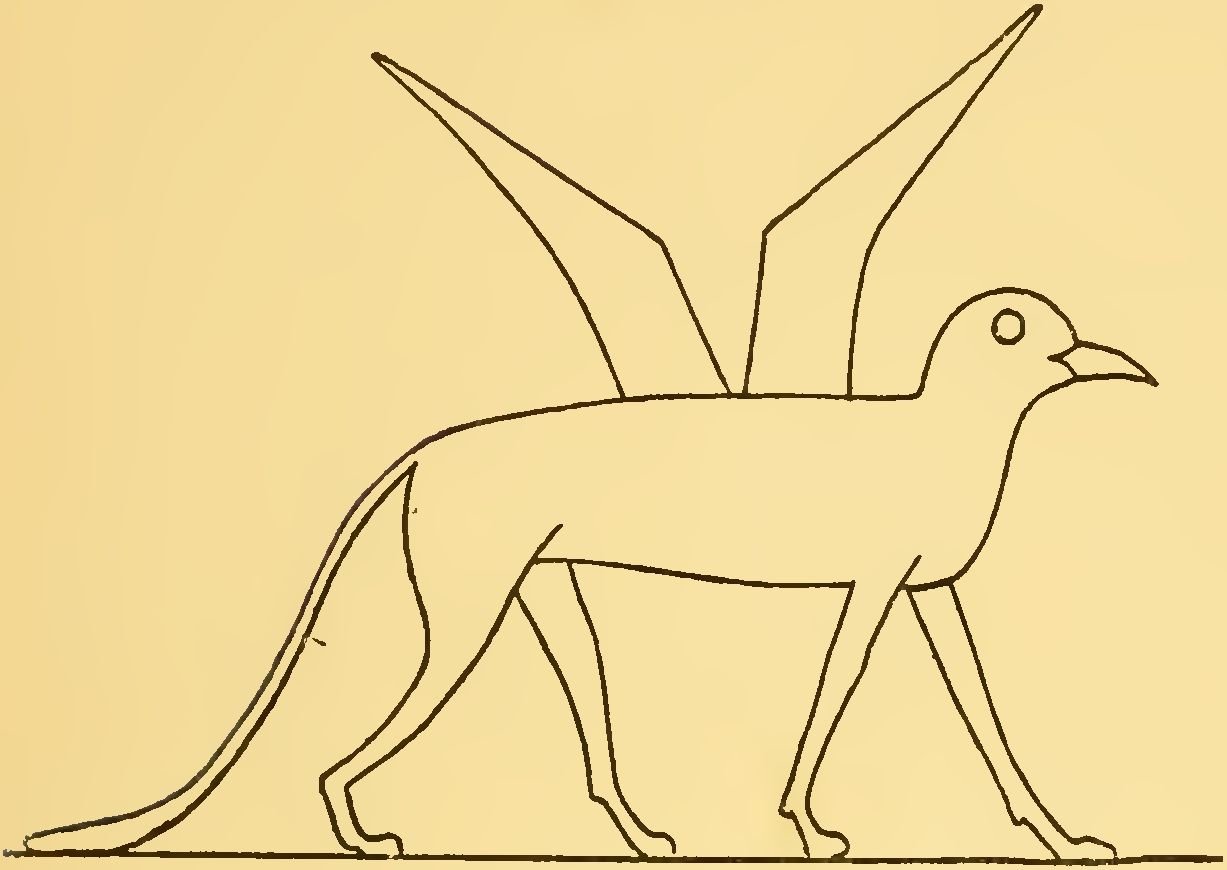

Image right 2: The eagle-headed lion Sefer.

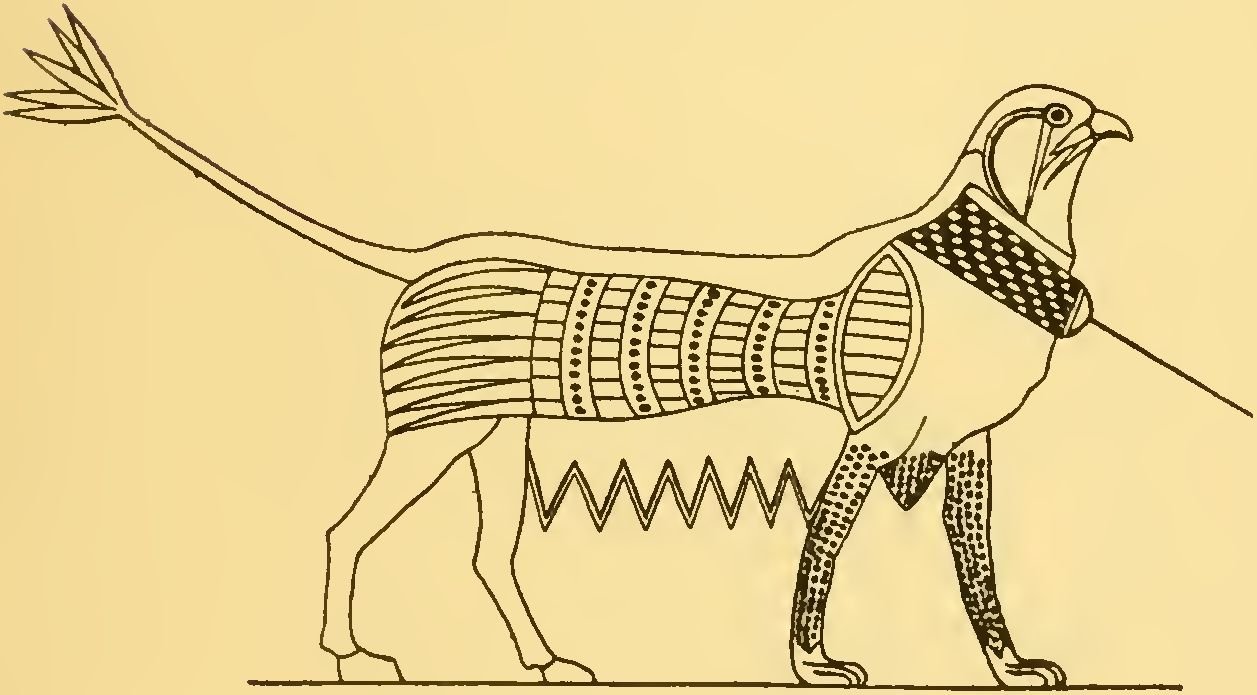

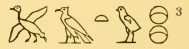

Among the latter class may be mentioned the creature which has the body of a leopard and the head and neck of a serpent, and was called “Setcha,”  ; and that which has the body of a lion, from which grow a pair of wings, and the head of an eagle, and is called “Sefer,”

; and that which has the body of a lion, from which grow a pair of wings, and the head of an eagle, and is called “Sefer,”

and that which has a body, the fore part being that of a lion, and the hind part that of a horse, and the head of a hawk, and an extended tail which terminates in a flower somewhat resembling the lotus.

and that which has a body, the fore part being that of a lion, and the hind part that of a horse, and the head of a hawk, and an extended tail which terminates in a flower somewhat resembling the lotus.

; and that which has the body of a lion, from which grow a pair of wings, and the head of an eagle, and is called “Sefer,”

; and that which has the body of a lion, from which grow a pair of wings, and the head of an eagle, and is called “Sefer,”

and that which has a body, the fore part being that of a lion, and the hind part that of a horse, and the head of a hawk, and an extended tail which terminates in a flower somewhat resembling the lotus.

and that which has a body, the fore part being that of a lion, and the hind part that of a horse, and the head of a hawk, and an extended tail which terminates in a flower somewhat resembling the lotus.

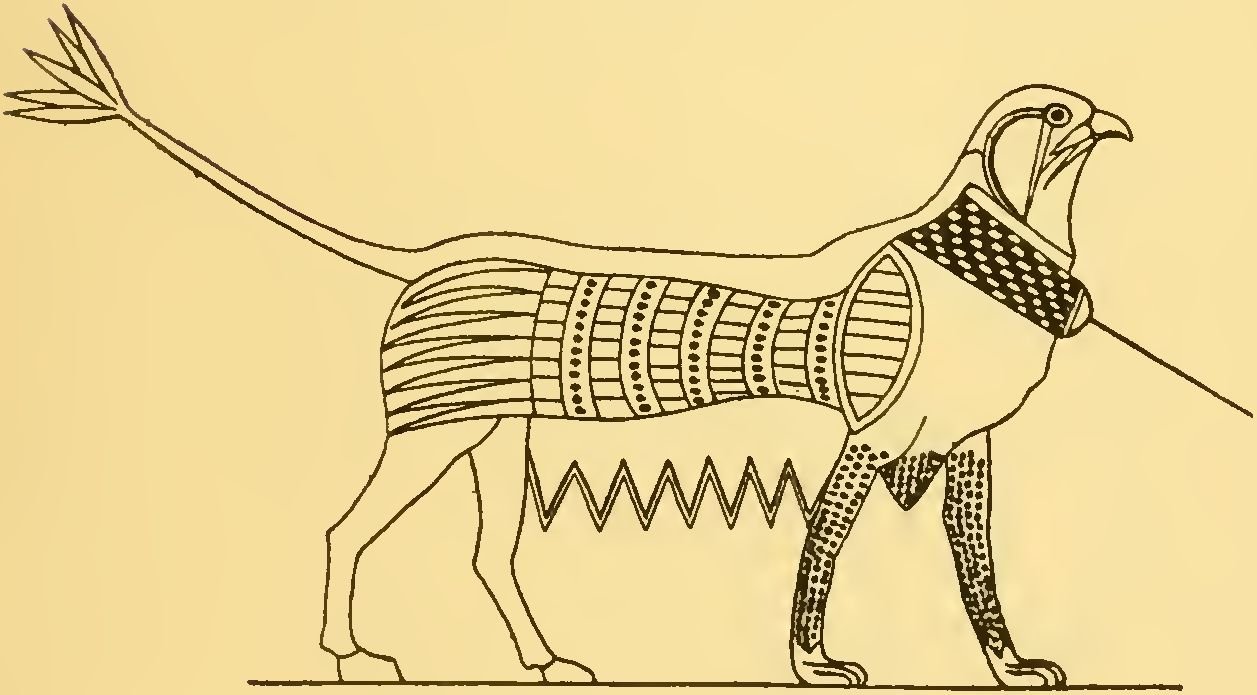

Image right: The fabulous beast Saḳ.

The name of this creature is Saḳ, , and she is represented with a collar round her neck, and with bars and stripes on her body, which has eight teats.

, and she is represented with a collar round her neck, and with bars and stripes on her body, which has eight teats.

, and she is represented with a collar round her neck, and with bars and stripes on her body, which has eight teats.

, and she is represented with a collar round her neck, and with bars and stripes on her body, which has eight teats.Image right: A fabulous leopard.

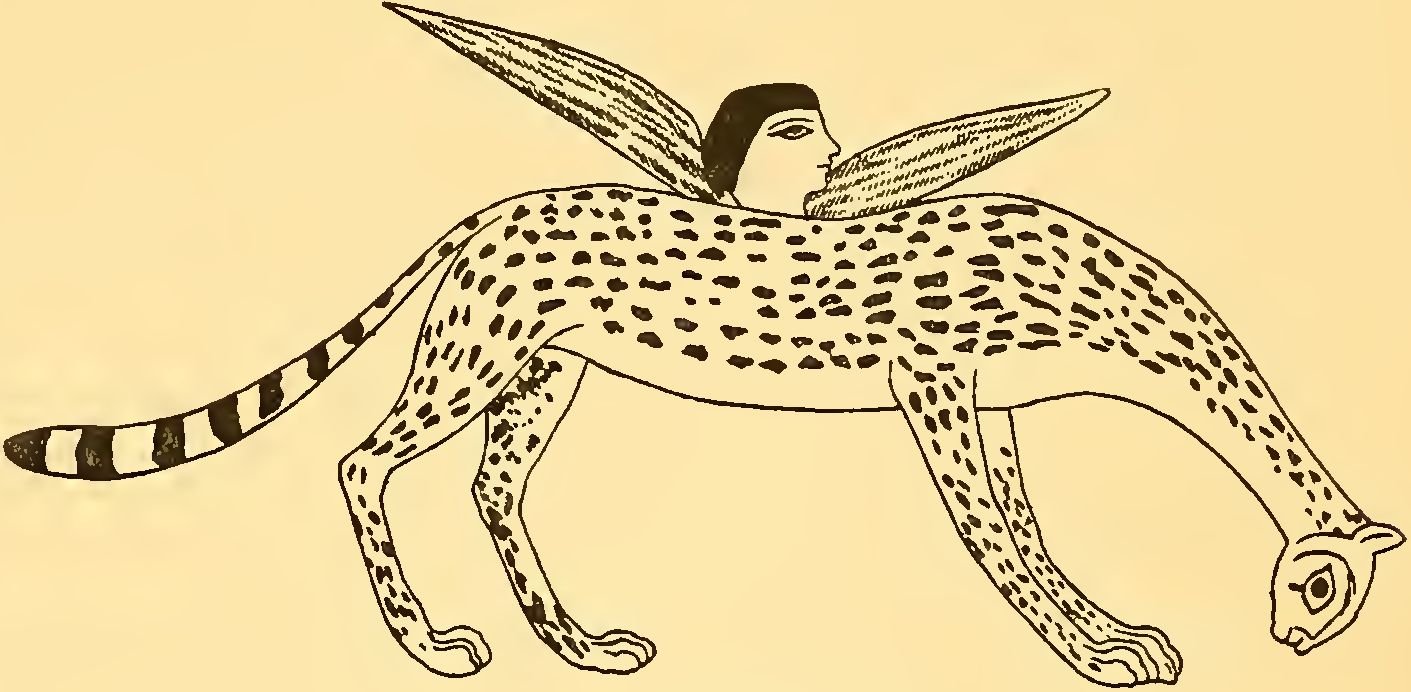

Among creatures, part animal part human, may be mentioned the leopard, with a human head and a pair of wings growing out of his back, and the human - headed lion or sphinx.

The winged human head which springs from the back of the leopard strongly reminds one of the modern conventional representations of angels in religious pictures, but as the name of this fabulous creature is unknown, it is impossible even to guess at the reasons for which he was furnished with a winded man’s head.

In connexion with the composite animals enumerated above must be mentioned the “Devourer of Ȧmenti,” called “Ām-mit, the Eater of the Dead,” whose forequarters were those of a crocodile, and hindquarters those of a hippopotamus, and whose body was that of a lion,

.

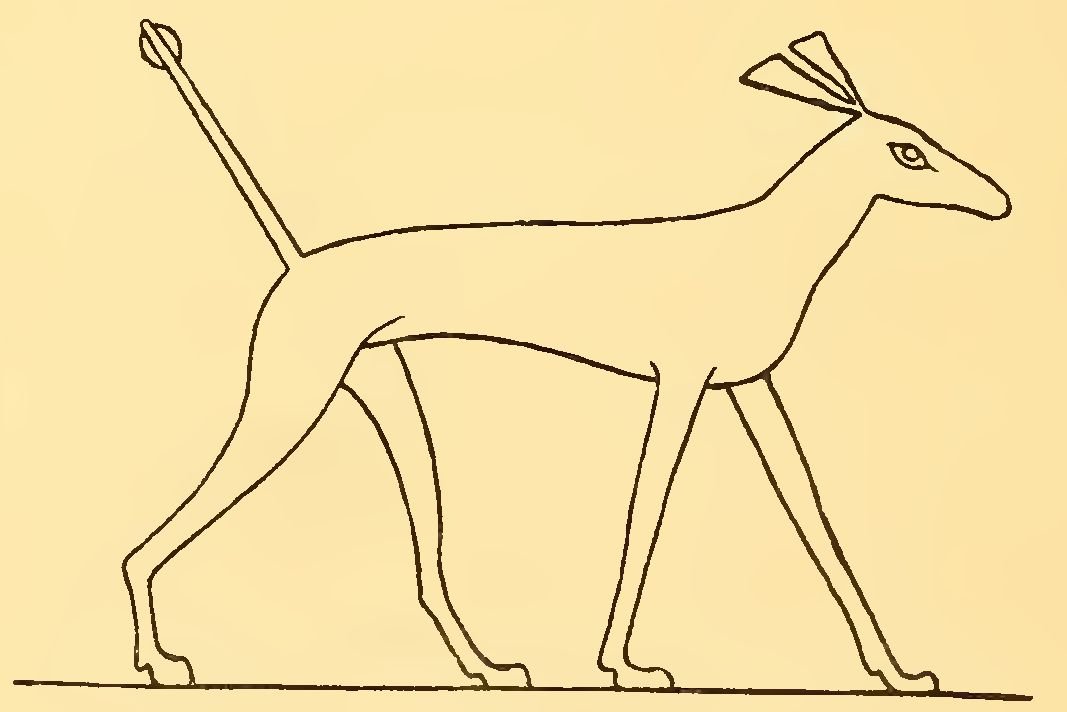

Image right: The animal Sha.

The tombs at Beni-hasan, in Avhich the figures of the Setcha, the Sefer, and the Sak are depicted, date from the XIIth Dynasty, about B.C. 2500, and there is no reason for supposing that their existence Avas not conceived of long before that time. Side by side with these is also depicted an animal called Sha, , which has long square ears, and an extended tail resembling an arrow, and in its general appearance it much resembles the animal of the god Set.

, which has long square ears, and an extended tail resembling an arrow, and in its general appearance it much resembles the animal of the god Set.

, which has long square ears, and an extended tail resembling an arrow, and in its general appearance it much resembles the animal of the god Set.

, which has long square ears, and an extended tail resembling an arrow, and in its general appearance it much resembles the animal of the god Set.

Two explanations of the existence of such composite creatures may be given. They may be due either to the imagination of the Egyptians, which conceived of the existence of quadrupeds wherein were united the strength of one animal and the wisdom or cunning of another, e.g., the Setcha which united within itself the strength of the leopard with the cunning of the serpent, and the nameless leopard with a man’s winged head, or to the ignorance of the ancients of natural history.

The human head on an animal represented the intelligence of a man, and the wings the swift flight of the bird, and the body of the leopard the strength and the lithe motions of that animal. In conceiving the existence of such creatures the imagination may have been assisted in its fabrication of fabulous monsters by legends or stories of pre-dynastic animals which were current in certain parts of Egypt during the dynastic period.

Thus, as we have said before, the monster serpents of Egyptian mythology have their prototypes in the huge serpents which lived in the country in primeval times, and there is no doubt that Āpep was, originally, nothing more than a huge serpent which lived in some mountain on the western bank of the Nile. On the other hand, it is possible that the Egyptians really believed in the existence of composite animals, and that they never understood the impossibility of the head and neck of a serpent growing out of the body of a lion, or the head of a hawk out of the body of a lion, or a human head with the wings of a bird out of the body of a leopard.

They were keen enough observers of the animals with which they came in contact daily, and their representations of them are wonderful for the accurate delineation of their forms and characteristics; but of animals which they had never seen, and could only know from the reports of travellers and others, naturally they could not give accurate representations. Man in all ages seems prone to believe in the existence of composite animals and monsters, and the most cultured of the most ancient nations, e.g., the Egyptians and the Babylonians, form no exception to the rule.

The early seal-cylinders of the Babylonians reveal their belief in the existence of many a fabulous and mythical animal, ai.d the boundary stones, or landmarks, of a later period prove that composite animals were supposed to watch over the boundaries of kingdoms and estates, which they preserved from invasion, and the winged man-headed bulls, which the Assyrians set up in the gates and doorways of their palaces to “protect the footsteps of the kings who made them,” indicate clearly that they duly followed the examples set them by their kinsmen, the Babylonians.

From the Assyrians Ezekiel probably borrowed the ideas which he developed in his description in the first chapter of his book of the four-faced and four-winged animals. Later, even the classical writers appeared to see no absurdity in solemnly describing animals, the existence of which was impossible, and in declaring that they possessed powers which were contrary to all experience and knowledge.

Horapollo, i. 10, gravely states that the scarabaeus represents an only begotten, because the scarabaeus is a creature self-produced, being unconceived by a female, μονογενές μεν οτι αντογενες εστι το ζώον, νπο θηλείας μη κνοφορονμενον; and in one form or another this statement is given by

Ælian (De. Nat. Animal., iv. 49),

Aristotle (Hist. An., iv. 7),

Porphyry (De Abstinentia, iv. 9),

Pliny (Nat. Hist., xi. 20 ff.),

etc.

Aristotle (Hist. An., iv. 7),

Porphyry (De Abstinentia, iv. 9),

Pliny (Nat. Hist., xi. 20 ff.),

etc.

Of the man-headed lion at Gîzeh, i.e., the Sphinx, Pliny, Diodorus, Strabo, and other ancient writers have given long descriptions, and all of them seem to take for granted the existence of such a creature.

The second explanation, which declares that composite animals are the result of the imagination of peoples who have no knowledge, or at all events a defective one, of the common facts of natural history is not satisfactory, for the simple reason that composite animals which are partly animal and partly human in their powers and characteristics form the logical link between animals and man, and as such they belong to a certain period and stage of development in the history of every primitive people. If we think for a moment we shall see that many of the gods of Egypt are closely connected with this stage of development, and that comparatively few of them were ever represented wholly in man’s form.

The Egyptians clung to their representations of gods in animal forms with great tenacity, and even in times when it is certain they cannot have believed in their existence they continued to have them sculptured and painted upon the walls of their temples ; curiously enough, they do not seem to have been sensible of the ridicule which their conservatism brought down upon them from strangers.

The Word Neter

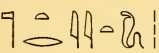

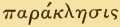

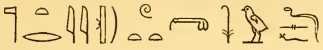

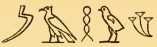

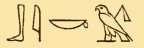

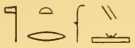

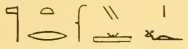

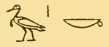

We have already said above that the common word given by the Egyptians to God, and god, and spirits of every kind, and beings of all sorts, and kinds, and forms, which were supposed to possess any superhuman or supernatural power, was neter,  , and the hieroglyph which is used both as the determinative of this word and also as an ideograph is

, and the hieroglyph which is used both as the determinative of this word and also as an ideograph is  .

.

, and the hieroglyph which is used both as the determinative of this word and also as an ideograph is

, and the hieroglyph which is used both as the determinative of this word and also as an ideograph is  .

.

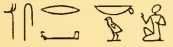

Thus we have

or

,

“god,”

and

, or

, or

, or

,

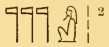

“gods;”

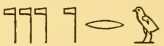

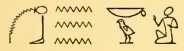

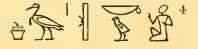

the plural is sometimes written out in full, e.g.,  . The common word for “goddess” is netert, which can be written

. The common word for “goddess” is netert, which can be written  , or

, or  , or

, or  ; sometimes the determinative of the word is a woman,

; sometimes the determinative of the word is a woman,  , and at other times a serpent, e.g.

, and at other times a serpent, e.g.  . The plural is neterit,

. The plural is neterit,  . We have now to consider what object is supposed to be represented by

. We have now to consider what object is supposed to be represented by  , and what the word neter means.

, and what the word neter means.

. The common word for “goddess” is netert, which can be written

. The common word for “goddess” is netert, which can be written  , or

, or  , or

, or  ; sometimes the determinative of the word is a woman,

; sometimes the determinative of the word is a woman,  , and at other times a serpent, e.g.

, and at other times a serpent, e.g.  . The plural is neterit,

. The plural is neterit,  . We have now to consider what object is supposed to be represented by

. We have now to consider what object is supposed to be represented by  , and what the word neter means.

, and what the word neter means.

In Bunsen’s Egypt’s Place (i., Nos. 556, 557, 623) the late Dr. Birch described  as a hatchet; in 1872 Dr. Brugsch placed

as a hatchet; in 1872 Dr. Brugsch placed  among “objets tranchants, armes,” in his classified list of hieroglyphic characters ; thus it is clear that the two greatest masters of Egyptology considered

among “objets tranchants, armes,” in his classified list of hieroglyphic characters ; thus it is clear that the two greatest masters of Egyptology considered to be either a weapon or a cutting tool, and, in fact, assumed that the hieroglyphic represented an axe-head let into and fastened in a long wooden handle. From the texts wherein the hieroglyphics are coloured it is tolerably clear that the axe-head was fastened to its handle by means of thongs of leather.

to be either a weapon or a cutting tool, and, in fact, assumed that the hieroglyphic represented an axe-head let into and fastened in a long wooden handle. From the texts wherein the hieroglyphics are coloured it is tolerably clear that the axe-head was fastened to its handle by means of thongs of leather.

as a hatchet; in 1872 Dr. Brugsch placed

as a hatchet; in 1872 Dr. Brugsch placed  among “objets tranchants, armes,” in his classified list of hieroglyphic characters ; thus it is clear that the two greatest masters of Egyptology considered

among “objets tranchants, armes,” in his classified list of hieroglyphic characters ; thus it is clear that the two greatest masters of Egyptology considered to be either a weapon or a cutting tool, and, in fact, assumed that the hieroglyphic represented an axe-head let into and fastened in a long wooden handle. From the texts wherein the hieroglyphics are coloured it is tolerably clear that the axe-head was fastened to its handle by means of thongs of leather.

to be either a weapon or a cutting tool, and, in fact, assumed that the hieroglyphic represented an axe-head let into and fastened in a long wooden handle. From the texts wherein the hieroglyphics are coloured it is tolerably clear that the axe-head was fastened to its handle by means of thongs of leather.

The earliest axe-heads were made of stone, or flint or chert, and later of metal, and it is certain that when copper, bronze, and iron took the place of stone or flint, the method by which the head was fastened to the handle was considerably modified.

Recently an attempt has been made to show that the axe, , resembled in outline

, resembled in outline

, resembled in outline

, resembled in outline“a roll of yellow cloth, the lower part bound or laced over, the upper part appearing as a flap at the top probably for unwinding. It is possible, indeed, that the present object represents a fetish, e.g., a bone carefully wound round with cloth and not the cloth alone.”

But it need hardly be said that no evidence for the correctness of these views is forthcoming. Whether the hieroglyphic was copied from something which was a roll of cloth or a fetish matters little, for the only rational determination of the character is that which has already been made by Drs. Birch and Brugsch, and the object which is represented by

was copied from something which was a roll of cloth or a fetish matters little, for the only rational determination of the character is that which has already been made by Drs. Birch and Brugsch, and the object which is represented by is, in the writers opinion, an axe and nothing else.

is, in the writers opinion, an axe and nothing else.

was copied from something which was a roll of cloth or a fetish matters little, for the only rational determination of the character is that which has already been made by Drs. Birch and Brugsch, and the object which is represented by

was copied from something which was a roll of cloth or a fetish matters little, for the only rational determination of the character is that which has already been made by Drs. Birch and Brugsch, and the object which is represented by is, in the writers opinion, an axe and nothing else.

is, in the writers opinion, an axe and nothing else.The Axe, Symbol Of God

Mr. Legge has collected a number of examples of the presence of the axe as an emblem of divinity on the megaliths of Brittany and in the prehistoric remains of the funeral caves of the Marne, of Scandinavia, and of America, and, what is very much to the point, he refers to an agate cylinder which was published by the late Adrien de Longpérier, wherein is a representation of a priest in Chaldaean garb offering sacrifice to an axe standing upright upon an altar.

Mr. Legge points out

“that the axe appears on these monuments not as the representation of an bject in daily use, but for religious or magical purposes,”

and goes on to say that this is proved by the

“fact that it is often found as a pendant and of such materials as gold, lead, and even amber; while that it is often represented with the peculiar fastenings of the earlier flint weapon shows that its symbolic use goes back to the neolithic and perhaps the palaeolithic age.’"

He is undoubtedly correct in thinking that the use of the stone axe precedes that of the flint arrow-head or flint knife, and many facts could be adduced in support of this view. The stone tied to the end of a stick formed an effective club, which was probably the earliest weapon known to the predynastic Egyptians, and subsequently man found that this weapon could be made more effective still by making the stone flat and by rubbing down one end of it to form a cutting edge.

The earliest axe-head had a cutting edge at each end, and was tied by leather thongs to the end of a stick by the middle, thus becoming a double axe ; examples of such a weapon appear to be given on the green slate object of the archaic period which is preserved in the British Museum (Nos. 20,790, 20,792), where, however, the axe-heads appear to be fixed in forked wooden handles. In its next form the axe-head has only one cutting edge, and the back of it is shaped for fastening to a handle by means of leather thongs. When we consider the importance that the axe, whether as a weapon or tool, was to primitive man, we need not wonder that it became to him first the symbol of physical force, or strength, and then of divinity or dominion.

By means of the axe the predynastic Egyptians cut down trees and slaughtered animals, in other words, the weapon was mightier than the spirits or gods who dwelt in the trees and the animals, and as such became to them at a very early period an object of reverence and devotion. But besides this the axe must have been used in sacrificial ceremonies, wherein it would necessarily acquire great importance, and would easily pass into the symbol of the ceremonies themselves. The shape of the axe-head as given by the common hieroglyphic suggests that the head was made of metal when the Egyptians first began to use the character as the symbol of divinity, and it is clear that this change in the material of which the axe-head was made would make the weapon more effective than ever.

suggests that the head was made of metal when the Egyptians first began to use the character as the symbol of divinity, and it is clear that this change in the material of which the axe-head was made would make the weapon more effective than ever.

suggests that the head was made of metal when the Egyptians first began to use the character as the symbol of divinity, and it is clear that this change in the material of which the axe-head was made would make the weapon more effective than ever.

suggests that the head was made of metal when the Egyptians first began to use the character as the symbol of divinity, and it is clear that this change in the material of which the axe-head was made would make the weapon more effective than ever.

Taking for granted, then, that the hieroglyphic represents an axe, we may be sure that it was used as a symbol of power and divinity by the predynastic Egyptians long before the period when they were able to write, but we have no means of knowing what they called the character or the axe before that period. In dynastic times they certainly called it neter as we have seen, but another difficulty presents itself to us when we try to find a word that will express the meaning which they attached to the word ; it is most important to obtain some idea of this meaning, for at the hase of it lies, no doubt, the Egyptian conception of divinity or God.

represents an axe, we may be sure that it was used as a symbol of power and divinity by the predynastic Egyptians long before the period when they were able to write, but we have no means of knowing what they called the character or the axe before that period. In dynastic times they certainly called it neter as we have seen, but another difficulty presents itself to us when we try to find a word that will express the meaning which they attached to the word ; it is most important to obtain some idea of this meaning, for at the hase of it lies, no doubt, the Egyptian conception of divinity or God.

represents an axe, we may be sure that it was used as a symbol of power and divinity by the predynastic Egyptians long before the period when they were able to write, but we have no means of knowing what they called the character or the axe before that period. In dynastic times they certainly called it neter as we have seen, but another difficulty presents itself to us when we try to find a word that will express the meaning which they attached to the word ; it is most important to obtain some idea of this meaning, for at the hase of it lies, no doubt, the Egyptian conception of divinity or God.

represents an axe, we may be sure that it was used as a symbol of power and divinity by the predynastic Egyptians long before the period when they were able to write, but we have no means of knowing what they called the character or the axe before that period. In dynastic times they certainly called it neter as we have seen, but another difficulty presents itself to us when we try to find a word that will express the meaning which they attached to the word ; it is most important to obtain some idea of this meaning, for at the hase of it lies, no doubt, the Egyptian conception of divinity or God.The Word Neter

The word neter has been discussed by many Egyptologists, but their conclusions as to its signification are not identical. M. Pierret thought in 1879 that the true meaning of the word is

“renewal, because in the mythological conception, the god assures himself everlasting youth by the renewal of himself in engendering himself perpetually.”

In the same year, in one of the Hibbert Lectures, Renouf declared that he was

“able to affirm with certainty that in this particular case we can accurately determine the primitive notion attached to the word,”

i.e., to nutar (neter). According to him,

“none of the explanations hitherto given of it can be considered satisfactory,”

but he thought that the explanation which he was about to propose would

“be generally accepted by scholars,”

because it was

“arrived at as the result of a special study of all the published passages in which the word occurs.”

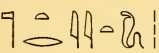

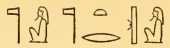

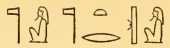

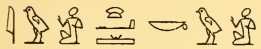

Closely allied to nutar (neter) is another word nutka (netra), and the meaning of both was said by Renouf to be found in the Coptic or

or , which, as we may see from the passages quoted by Tatham in his Lexicon (p. 310), is rendered by the Greek words

, which, as we may see from the passages quoted by Tatham in his Lexicon (p. 310), is rendered by the Greek words ,

, , and

, and .

.

or

or , which, as we may see from the passages quoted by Tatham in his Lexicon (p. 310), is rendered by the Greek words

, which, as we may see from the passages quoted by Tatham in his Lexicon (p. 310), is rendered by the Greek words ,

, , and

, and .

.

The primary meaning of the word  appears to be “strong,” and having assumed that neter was equivalent in meaning to this word, Renouf stated boldly that neter signified “mighty,” “might,” “strong,” and argued that it meant Power, “which is also the meaning of the Hebrew El.” We may note in passing that the exact meaning of “El,” the Hebrew name for God, is unknown, and that the word itself is probably the name of an ancient Semitic deity.

appears to be “strong,” and having assumed that neter was equivalent in meaning to this word, Renouf stated boldly that neter signified “mighty,” “might,” “strong,” and argued that it meant Power, “which is also the meaning of the Hebrew El.” We may note in passing that the exact meaning of “El,” the Hebrew name for God, is unknown, and that the word itself is probably the name of an ancient Semitic deity.

appears to be “strong,” and having assumed that neter was equivalent in meaning to this word, Renouf stated boldly that neter signified “mighty,” “might,” “strong,” and argued that it meant Power, “which is also the meaning of the Hebrew El.” We may note in passing that the exact meaning of “El,” the Hebrew name for God, is unknown, and that the word itself is probably the name of an ancient Semitic deity.

appears to be “strong,” and having assumed that neter was equivalent in meaning to this word, Renouf stated boldly that neter signified “mighty,” “might,” “strong,” and argued that it meant Power, “which is also the meaning of the Hebrew El.” We may note in passing that the exact meaning of “El,” the Hebrew name for God, is unknown, and that the word itself is probably the name of an ancient Semitic deity.

The passages which were quoted to prove that neter meant “strong, strength, power,” and the like could, as M. Maspero has said, be explained differently.

M. Maspero combats rightly the attempt to make “strong” the meaning of neter (masc.), or neterit (fem.), in these words:

“In the expressions‘a town neterit,’

‘an arm neteri,’ ....is it certain that‘a strong city,’

‘a strong arm,’gives us the primitive sense of neter?When among ourselves one says‘divine music,’

‘a piece of divine poetry,’

‘the divine taste of a peach,’

‘the divine beauty of a woman’[the word] divine is a hyperbole, but it would be a mistake to declare that it originally meant ‘exquisite’ because in the phrases which I have imagined one could apply it as‘exquisite music,’

‘a piece of exquisite poetry,’

‘the exquisite taste of a peach,’

‘the exquisite beauty of a woman.’Similarly in Egyptian‘a town neteriťis a‘divine town’;[and]‘an arm neteri’is‘a divine arm,’and neteri is employed metaphorically in Egyptian as is [the word] ‘divine’ in French, without its being any more necessary to attribute to [the word] neteri the primitive meaning of ‘strong,’ than it is to attribute to [the word] ‘divine’ the primitive meaning of ‘exquisite.’The meaning ‘strong’ of neteri, if it exists, is a derived and not an original meaning.”

The view taken about the meaning of neter by the late Dr. Brugsch was entirely different, for he thought that the fundamental meaning of the word was

“the operative power which created and produced things by periodical recurrence, and gave them new life and restored to them the freshness of youth (die thätige Kraft, welche in periodischer Wiederkehr die Dinge erzeugt und erschafft, ihnen neues Leben verleiht und die Jugendfrische zurückgiebt.”

The first part of the work from which these words are quoted appeared in 1885, but that Dr. Brugsch held much the same views six years later is evident from the following extract from his volume entitled Die Aegypto-iogie (p. 166), which appeared in 1891. Referring to Renouf’s contention that neter has a meaning equivalent to the Greek  , he says,

, he says,

, he says,

, he says,“Es liegt auf der Hand, dass der Gottesname in Sinne von Starker, Mächtiger, vieles fur sich hat, um so mehr als selbst leblose Gegenstände, wie z. B. ein Baustein, adjektivisch als nutri d. h. stark, mächtig, nicht selten bezeichnet werden.Aber so vieles diese Erklärung für sich zu haben schient, so wenig stimmt sie zu der Thatsache, dass in den Texten aus der besten Zeit (XVIII Dynastie) das Wort nutr als ein Synonym für die Vorstellung der Verjungung oder Erneuerung auftritt.Es diente zum Ausdruck der periodisch wiederkehrenden Jugendfrische nach Alter und Tod, so dass selbst dem Menschen in den ältesten Sarginschriften zugerufen wird, er sei fortan in einen Gott d. h. in ein Wesen mit jugendlicher Frische umgewandelt.Ich lasse es dahin gestellt sein, nach welcher Richtung hin die aufgeworfene Streitfrage zu Gunsten der einen oder der anderen Auffassung entschieden werden wird; hier sei nur betont, dass das Wortnutr, nute, den eigentlichen Gottesbegriff der alten Aegypter in sich schliesst und daher einen ganz besonderen Aufmerksamkeit werth ist”

In this passage Dr. Brugsch substantially agrees with Pierreťs views quoted above, but he appears to have withdrawn from the position which he took up in his Religion und Mythologie, wherein he asserted that the essential meaning of neter was identical with that of the Greek {PLAATJE_NOG_UITSNEIDEN} and the Latin “natura.”

It need hardly be said that there are no good grounds for such an assertion, and it is difficult to see how the eminent Egyptologist could attempt to compare the conceptions of God formed by a half-civilized African people with those of such cultured nations as the Greeks and the Romans.

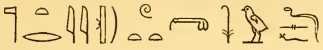

The solution of the difficulty of finding a meaning for neter is not brought any nearer when we consider the views of such distinguished Egyptologists as E. de Rouge, Lieblein, and Maspero. The first of these in commenting on the passage (variant

(variant , which he translates “Dieu devenant dieu (en) s’engendrant lui-même,” says in his excellent Ohrestomathie Égyptienne (iii. p. 24),

, which he translates “Dieu devenant dieu (en) s’engendrant lui-même,” says in his excellent Ohrestomathie Égyptienne (iii. p. 24),

(variant

(variant , which he translates “Dieu devenant dieu (en) s’engendrant lui-même,” says in his excellent Ohrestomathie Égyptienne (iii. p. 24),

, which he translates “Dieu devenant dieu (en) s’engendrant lui-même,” says in his excellent Ohrestomathie Égyptienne (iii. p. 24),“One knows not exactly the meaning of the verb miter, which forms the radical of the word nuter, ‘god.’ It is an idea analagous to to ‘become’ or ‘renew oneself,’ for nuteri is applied to the resuscitated soul which clothes itself in its immortal form.”

Thus we find that one of the greatest Egyptologists thinks that the exact meaning of neter is unknown, but he suggests that it may have a signification not unlike that proposed by Pierret. Prof. Lieblein goes a step further than E. de Rouge, for he is of opinion that it is impossible to show the first origin of the idea of God among any people hitherto known historically.

“When we, for instance, take the Indo-Europeans, what do we find there? The Sanskrit word deva is identical with the Latin deus, and the northern tivi, tivar; as now the word in Latin and northern language signifies God it must also in Sanskrit from the beginning have had the same signification.That is to say, the Arians, or Indo-Europeans, must have combined the idea of God with this word, as early as when they still lived together in their original home. Because, if the word in their pre-historic home had had another more primitive signification, the wonder would have happened, that the word had accidentally gone through the same development of signification with all these people after their separation. As this is quite improbable, the word must have had the signification of God in the original Indo-European language.One could go even farther and presume that, in this language also, it was a word derived from others, and consequently originated from a still earlier pre-historic language. All things considered it is possible, even probable, that the idea of God has developed itself in an earlier period of languages, than the Indo-European. The future will perhaps be able to supply evidence for this.The science of languages has been able partly to reconstruct an Indo-European pre-historic language. It might be able also to reconstruct a pre-historic Semitic, and a pre-historic Hamitic, and of these three pre-historic languages, whose original connexion it not only guesses, but even commences to prove gradually, it will, we trust in time, be able to extract a still earlier pre-historic language, which according to analogy might be called Noahitic.When we have come so far, we shall most likely in this pre-historic language, also find words expressing the idea of God. But it is even possible that the idea of God has not come into existence in this pre-historic language either. It may be that the first dawning of the idea, and the word God should be ascribed to still earlier languages, to layers of languages so deeply buried that it will be impossible even to excavate them.Between the time of inhabiting caves in the quaternian period, and the historical kingdoms, there is such a long space of time, that it is difficult to entertain the idea, that it was quite devoid of any conception of divinity, so that this should first have sprung up in the historical time. In any case we shall not be able to prove historically where and when the question first arose, who are the superhuman powers whose activity we see daily in nature and in human life.Although the Egyptians are the earliest civilized people known in history, and just therefore especially important for the science of religion, yet it is even there impossible to point out the origin of the conception of the deity. The oldest monuments of Egypt bring before us the gods of nature chiefly, and among these especially the sun.They mention, however, already early (in the IVth and Vth Dynasties) now and then the great power, or the great God, it being uncertain whether this refers to the sun, or another god of nature, or if it was a general appellation of the vague idea of a supernatural power, possibly inherited by the Egyptians. It is probably this great God indicated on the monuments, from the the IVth Dynasty, and later on, who has given occasion to the false belief that the oldest religion of the Egyptians was pure monotheism.But firstly, it must be observed, that lie is not mentioned alone but alongside of the other gods, secondly, that he is merely called ‘The great God,’ being otherwise without distinguishing appellations, and a God of whom nothing else is mentioned, has, so to speak, to use Hegel’s language, merely an abstract existence, that by closer examination dissolves into nothing.”

It is necessary to quote Professor Lieblein’s opinion at length because he was one of the first to discuss the earliest idea of God in connection with its alleged similarity to that evolved by Aryan nations ; if, however, he were to rewrite the passage given above in the light of modern research he would, we think, modify many of his conclusions. For our present purpose it is sufficient to note that he believes it is impossible to point out the origin of the conception of the deity among the Egyptians.

The last opinion which we need quote is that of M. Maspero, who not only says boldly that if the word neter or netri really has the meaning of “strong” it is a derived and not an original meaning, and he prefers to declare that the word is so old that its earliest signification is unknown. In other words, it has the meaning of god, but it teaches us nothing as to the primitive value of this word. We must be careful, he says, not to let it suggest the modern religious or philosophical definitions of god which are current to-day, for an Egyptian god is a being who is born and dies, like man, and is finite, imperfect, and corporeal, and is endowed with passions, and virtues, and vices.

This statement is, of course, true as regards the gods of the Egyptians at several periods of their history, but it must be distinctly understood, and it cannot be too plainly stated, that side by side with such conceptions there existed, at least among the educated Egyptians, ideas of monotheism which are not far removed from those of modern nations.

From what has been said above we see that some scholars take the view that the word neter may mean “renewal,” or “strength,” or “strong,” or “to become,” or some idea which suggests “renewal,” and that others think its original meaning is not only unknown, but that it is impossible to find it out. But although we may not be able to discover the exact meaning which the word had in predynastic times, we may gain some idea of the meaning which was attached to it in the dynastic period by an examination of a few passages from the hymns and Chapters which are found in the various versions of the Book of the Dead.

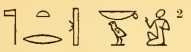

In the text of Pepi I. (line 191) we have the words:—

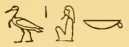

“Behold thy son Horus, to whom thou hast given birth. He hath not placed this Pepi at the head of the dead, but he hath set him among the gods neteru,”.

Now here neteru, , must be an adjective, and we are clearly intended to understand that the gods referred to are those which have the attribute of neteru; since the “gods neteru,”

, must be an adjective, and we are clearly intended to understand that the gods referred to are those which have the attribute of neteru; since the “gods neteru,” , are mentioned in opposition to “the dead” it seems as if we are to regard the gods as “living,” i.e., to possess the quality of life. In the text of the same king (line 419) a bȧk neter,

, are mentioned in opposition to “the dead” it seems as if we are to regard the gods as “living,” i.e., to possess the quality of life. In the text of the same king (line 419) a bȧk neter, , i.e., a hawk having the quality of neter is mentioned;and in the text of Unȧs (line 569) we read of baui netrui,

, i.e., a hawk having the quality of neter is mentioned;and in the text of Unȧs (line 569) we read of baui netrui, , or the two souls which possess the quality of neter.

, or the two souls which possess the quality of neter.

, must be an adjective, and we are clearly intended to understand that the gods referred to are those which have the attribute of neteru; since the “gods neteru,”

, must be an adjective, and we are clearly intended to understand that the gods referred to are those which have the attribute of neteru; since the “gods neteru,” , are mentioned in opposition to “the dead” it seems as if we are to regard the gods as “living,” i.e., to possess the quality of life. In the text of the same king (line 419) a bȧk neter,

, are mentioned in opposition to “the dead” it seems as if we are to regard the gods as “living,” i.e., to possess the quality of life. In the text of the same king (line 419) a bȧk neter, , i.e., a hawk having the quality of neter is mentioned;and in the text of Unȧs (line 569) we read of baui netrui,

, i.e., a hawk having the quality of neter is mentioned;and in the text of Unȧs (line 569) we read of baui netrui, , or the two souls which possess the quality of neter.

, or the two souls which possess the quality of neter.

These examples belong to the Vth and VIth Dynasties. Passing to later dynasties, i.e., the XYIIIth and XIXth, etc., we find the following examples of the use of the words neter and netri:—

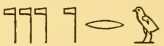

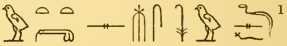

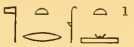

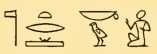

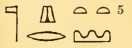

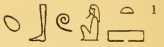

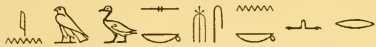

| 1. |  ḥun Boy |  netri netri, |  ȧā heir |  ḥeḥ of eternity, |  utet se-mes su tchesef begetting and giving birth to himself. |

| 2. |  ṭa-ȧ tu em ȧb-ȧ I am devoted in my heart |  ȧti without |  bakai feigning, |  netri O thou netri |

er more than |  neteru the gods. |

| 3. |  tcheṭ - tu re pen ḥer Shall be said this chapter over |  maḥu a crown |  en of |  meṭrat meṭrat. |

| 4. |  neter - ḳua I have become neter. |

| 5. |  ȧu - ȧ khā - kuȧ I have risen up |  em in |  bȧk the form of a hawk |  netri netri. |

| 6. |  āb - kuȧ I have become pure, |  neter - kuȧ I have become neter, |  khu - kuȧ I have become a spirit (lhu), |

user - kuȧ I have become strong, |  ba - kuȧ I have become a soul (ba). |

| 7. |  unen-f His being (or, he shall be) |  neter neter |  mā with |  neteru the gods |  em in the |  Neter-khertet Neter-khertet. |

| 8. |  ȧu - f He shall |  netrȧ netrả |  khat-f his body |  temtu all. |

| 9. |  netri They make |  u neter |  ba - k thy soul |  em in |  per the house of |  Sebut Sebut. |

| 10. |  netri - ƒ He makes neter |  ba - k thy soul |  mȧ like |  neteru the gods. |

| 11. |  neter God |  netri netri, |  kheper tchesef self-produced, |  paut primeval matter. |

Now, in the above examples it is easy to see that although the words “strong” or “strength,” when applied to translate neter or netri, give a tolerably suitable sense in some of them, it· is quite out of place in others, e.g., in No. 6, where the deceased is made to say that he has acquired the quality of neter, and a spirit, and a soul, and is, moreover, strong; the word rendered “strong” in this passage is user, and it expresses an entirely different idea from neter.

From the fact that neter is mentioned in No. 1 in connection with eternal existence, and self-begetting, and self-production, and in No. 11 with self-production and primeval matter, it is almost impossible not to think that the word has a meaning which is closely allied to the ideas of “self-existence,” and the power to “renew life indefinitely,” and “self-production.” In other words, neter appears to mean a being who has the power to generate, life, and to maintain it when generated.

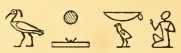

It is useless to attempt to explain the word by Coptic etymologies, for it has passed over directly into the Coptic language under the forms nouti  , and noute

, and noute  , the last consonant, r, having disappeared through phonetic decay, and the translators of the Holy Scriptures from that language used it to express the words “God” and “Lord.” Meanwhile, until new light is thrown upon the subject by the discovery of inscriptions older than any which we now have, we must be content to accept the approximate meaning of neter suggested above.

, the last consonant, r, having disappeared through phonetic decay, and the translators of the Holy Scriptures from that language used it to express the words “God” and “Lord.” Meanwhile, until new light is thrown upon the subject by the discovery of inscriptions older than any which we now have, we must be content to accept the approximate meaning of neter suggested above.

, and noute

, and noute  , the last consonant, r, having disappeared through phonetic decay, and the translators of the Holy Scriptures from that language used it to express the words “God” and “Lord.” Meanwhile, until new light is thrown upon the subject by the discovery of inscriptions older than any which we now have, we must be content to accept the approximate meaning of neter suggested above.

, the last consonant, r, having disappeared through phonetic decay, and the translators of the Holy Scriptures from that language used it to express the words “God” and “Lord.” Meanwhile, until new light is thrown upon the subject by the discovery of inscriptions older than any which we now have, we must be content to accept the approximate meaning of neter suggested above.

No comments:

Post a Comment