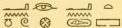

Kheperȧ-rā-temu

In the Myth of Rā and Isis Rā is made to say,

“I am Kheperȧ in the morning, and Rā at noonday, and Temu in the evening.”

From which we may understand that the day and the night were divided into three parts, each of which was presided over by one of the three forms of Rā here mentioned. In the time of the Middle Empire Tem is often mentioned with Ḥeru-khuti, Rā, and Kheperȧ, and the priests of Heliopolis always attempted to prove that he was the ancestor of all the other forms of the Sun-god.

In the Book of the Dead (xvii. 5 ff.) the deceased is made to identify himself with Tem as the oldest of the gods, and he says,

“I am Tem in rising ; I am the only One ; I came into being in Nu. I am Rā who rose in the beginning.”

The statement is followed by the question, “Who then is this?” and the answer is,

“It is Rā when at the beginning he rose in the city of Suten-ḥenen, crowned like a king in rising. The pillars of Shu were not as yet created when he was upon the high ground of him lUSAASET AND NEBT-HETEPthat dwelleth in Khemennu” (i.e., Thoth).

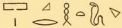

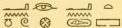

Thus it is clear that the Heliopolitans made out that it was Tern who was the first god to exist in primeval matter, and they consistently coupled him with Harmachis, , and with Kheperȧ,

, and with Kheperȧ, , as forms of the rising sun ; on the other hand, they often, with fine inconsistency, identified him with the setting sun, and made the wind of evening, which gave refreshment to mortals and breath to the dead, to go forth from him.

, as forms of the rising sun ; on the other hand, they often, with fine inconsistency, identified him with the setting sun, and made the wind of evening, which gave refreshment to mortals and breath to the dead, to go forth from him.

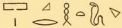

, and with Kheperȧ,

, and with Kheperȧ, , as forms of the rising sun ; on the other hand, they often, with fine inconsistency, identified him with the setting sun, and made the wind of evening, which gave refreshment to mortals and breath to the dead, to go forth from him.

, as forms of the rising sun ; on the other hand, they often, with fine inconsistency, identified him with the setting sun, and made the wind of evening, which gave refreshment to mortals and breath to the dead, to go forth from him.Shrines of Tem

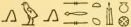

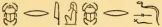

It is difficult to say definitely where the original shrine of Tem was situated, but it appears to have been in the Eighth Nome of Lower Egypt, ( , Nefer Ȧbt, the Heroopolites of the Greeks), at the place which is called both Thuket,

, Nefer Ȧbt, the Heroopolites of the Greeks), at the place which is called both Thuket,  , and Pa-Ȧtemt,

, and Pa-Ȧtemt,  , and it is described as the “gate of the East.” Under the form “Pithom” the sacred name of the city Pa-Ȧtemt is familiar to all from the Bible. The site of Pa-Ȧtemt or Pithom was long thought to be buried beneath the ruins called by the Arabs Tell al-Maskhûtah, which are situated close to the modern village of Tell el-Kebîr, and the excavations made on the spot by M. Naville prove that this view is correct.

, and it is described as the “gate of the East.” Under the form “Pithom” the sacred name of the city Pa-Ȧtemt is familiar to all from the Bible. The site of Pa-Ȧtemt or Pithom was long thought to be buried beneath the ruins called by the Arabs Tell al-Maskhûtah, which are situated close to the modern village of Tell el-Kebîr, and the excavations made on the spot by M. Naville prove that this view is correct.

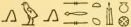

The inscriptions prove beyond all doubt that the great god of Pithom was Tem, and from the allusions which are made in them to the “Holy serpent” therein, and from the fact that one part of the temple buildings was called Pa-Qerḥet,  , or Ȧst-qerḥet,

, or Ȧst-qerḥet,  , that is, “the house of the snake-god Qerḥet,” it is tolerably certain that one of the forms under which Tem was worshipped was a huge serpent. A town situated as Pithom was on the large canal joining the Red Sea and the Nile, and on the highway from Arabia to Heliopolis must have contained a very mixed population, which would include a number of merchants and others from Western Asia.

, that is, “the house of the snake-god Qerḥet,” it is tolerably certain that one of the forms under which Tem was worshipped was a huge serpent. A town situated as Pithom was on the large canal joining the Red Sea and the Nile, and on the highway from Arabia to Heliopolis must have contained a very mixed population, which would include a number of merchants and others from Western Asia.

, or Ȧst-qerḥet,

, or Ȧst-qerḥet,  , that is, “the house of the snake-god Qerḥet,” it is tolerably certain that one of the forms under which Tem was worshipped was a huge serpent. A town situated as Pithom was on the large canal joining the Red Sea and the Nile, and on the highway from Arabia to Heliopolis must have contained a very mixed population, which would include a number of merchants and others from Western Asia.

, that is, “the house of the snake-god Qerḥet,” it is tolerably certain that one of the forms under which Tem was worshipped was a huge serpent. A town situated as Pithom was on the large canal joining the Red Sea and the Nile, and on the highway from Arabia to Heliopolis must have contained a very mixed population, which would include a number of merchants and others from Western Asia.

These probably brought in with them a number of strange practices connected with the worship of their own gods, which having been adopted by the indigenous peoples in the district modified their worship. From a passage in the Pyramid Texts already quoted it seems that the original form of the worship of Tem was phallic in character, but if it was . nothing is known about it; some scholars have regarded obelisks as phallic emblems, and have pointed to their earliest forms, in which their tops were surmounted by disks, in proof of the correctness of their view.

Iusāaset And Nebt-ḥetep

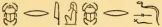

Attached to the god Tem were two female counterparts called respectively Iusāaset, , and Nebt-Ḥetep,

, and Nebt-Ḥetep,  , and they formed members of the company of the gods of Heliopolis, being mentioned with Tem, lord of the two lands of Ȧnnu, Rā, and Ḥeru-khuti. Iusāaset, the Σαωσις of Plutarch, is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,” and the “Eye of Rā,”

, and they formed members of the company of the gods of Heliopolis, being mentioned with Tem, lord of the two lands of Ȧnnu, Rā, and Ḥeru-khuti. Iusāaset, the Σαωσις of Plutarch, is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,” and the “Eye of Rā,”  , and she is regarded as the mother, and wife, and daughter of Tem according to the requirements of the texts; as the wife of Tem she is said to be the mother of Shu and Tefnut.

, and she is regarded as the mother, and wife, and daughter of Tem according to the requirements of the texts; as the wife of Tem she is said to be the mother of Shu and Tefnut.

, and Nebt-Ḥetep,

, and Nebt-Ḥetep,  , and they formed members of the company of the gods of Heliopolis, being mentioned with Tem, lord of the two lands of Ȧnnu, Rā, and Ḥeru-khuti. Iusāaset, the Σαωσις of Plutarch, is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,” and the “Eye of Rā,”

, and they formed members of the company of the gods of Heliopolis, being mentioned with Tem, lord of the two lands of Ȧnnu, Rā, and Ḥeru-khuti. Iusāaset, the Σαωσις of Plutarch, is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,” and the “Eye of Rā,”  , and she is regarded as the mother, and wife, and daughter of Tem according to the requirements of the texts; as the wife of Tem she is said to be the mother of Shu and Tefnut.

, and she is regarded as the mother, and wife, and daughter of Tem according to the requirements of the texts; as the wife of Tem she is said to be the mother of Shu and Tefnut.

She is depicted in the form of a woman who holds the sceptre,  , in her right hand, and “life,”

, in her right hand, and “life,”  , in her left; on her head she wears the vulture head-dress surmounted by a uraeus, and a disk between a pair of horns. In this form she is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,”

, in her left; on her head she wears the vulture head-dress surmounted by a uraeus, and a disk between a pair of horns. In this form she is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,”  , and was the wife of Tem-Ḥeru-khuti. The goddess Nebt-ḥetep appears to have been nothing but a form of Iusāaset, for in the scene in which she is represented in the form of a cow she is called “mistress of the gods, Iusāaset-Nebt-ḥetep.”

, and was the wife of Tem-Ḥeru-khuti. The goddess Nebt-ḥetep appears to have been nothing but a form of Iusāaset, for in the scene in which she is represented in the form of a cow she is called “mistress of the gods, Iusāaset-Nebt-ḥetep.”

, in her right hand, and “life,”

, in her right hand, and “life,”  , in her left; on her head she wears the vulture head-dress surmounted by a uraeus, and a disk between a pair of horns. In this form she is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,”

, in her left; on her head she wears the vulture head-dress surmounted by a uraeus, and a disk between a pair of horns. In this form she is called the “mistress of Ȧnnu,”  , and was the wife of Tem-Ḥeru-khuti. The goddess Nebt-ḥetep appears to have been nothing but a form of Iusāaset, for in the scene in which she is represented in the form of a cow she is called “mistress of the gods, Iusāaset-Nebt-ḥetep.”

, and was the wife of Tem-Ḥeru-khuti. The goddess Nebt-ḥetep appears to have been nothing but a form of Iusāaset, for in the scene in which she is represented in the form of a cow she is called “mistress of the gods, Iusāaset-Nebt-ḥetep.”

According to Brugsch Tem was joined to the god Osiris under the phase Tem-Ȧsȧr, and formed with Hathor of Ȧnnu, or Ānt,  , and Ḥeru-sma-taui,

, and Ḥeru-sma-taui,  , the head of the triad of Heroopolis. As local forms of the god Tem-Rā he enumerates Khnemu in Elephantine, Khnemu-Ḥeru-shefit in Heracleopolis Magna, and Khnemu-Ba-neb-Ṭeṭṭeṭ in Mendes.

, the head of the triad of Heroopolis. As local forms of the god Tem-Rā he enumerates Khnemu in Elephantine, Khnemu-Ḥeru-shefit in Heracleopolis Magna, and Khnemu-Ba-neb-Ṭeṭṭeṭ in Mendes.

, and Ḥeru-sma-taui,

, and Ḥeru-sma-taui,  , the head of the triad of Heroopolis. As local forms of the god Tem-Rā he enumerates Khnemu in Elephantine, Khnemu-Ḥeru-shefit in Heracleopolis Magna, and Khnemu-Ba-neb-Ṭeṭṭeṭ in Mendes.

, the head of the triad of Heroopolis. As local forms of the god Tem-Rā he enumerates Khnemu in Elephantine, Khnemu-Ḥeru-shefit in Heracleopolis Magna, and Khnemu-Ba-neb-Ṭeṭṭeṭ in Mendes.Kheperȧ

The third form of Rā, the Sun-god, was Kheperȧ kheper-tchesee,  , i.e., Kheperȧ the self-produced, whose type and symbol was a beetle ; he is usually represented in human form with a beetle upon the head, but sometimes a beetle takes the place of the thuman head. In one scene figured by Lanzone he is represented seated on the ground, and from his knees projects the head of the hawk of Horus, which is surmounted by

, i.e., Kheperȧ the self-produced, whose type and symbol was a beetle ; he is usually represented in human form with a beetle upon the head, but sometimes a beetle takes the place of the thuman head. In one scene figured by Lanzone he is represented seated on the ground, and from his knees projects the head of the hawk of Horus, which is surmounted by  , “life.”

, “life.”

, i.e., Kheperȧ the self-produced, whose type and symbol was a beetle ; he is usually represented in human form with a beetle upon the head, but sometimes a beetle takes the place of the thuman head. In one scene figured by Lanzone he is represented seated on the ground, and from his knees projects the head of the hawk of Horus, which is surmounted by

, i.e., Kheperȧ the self-produced, whose type and symbol was a beetle ; he is usually represented in human form with a beetle upon the head, but sometimes a beetle takes the place of the thuman head. In one scene figured by Lanzone he is represented seated on the ground, and from his knees projects the head of the hawk of Horus, which is surmounted by  , “life.”

, “life.”

In the section which treats of the Creation we have already translated and discussed the text which tells how the Sun-god Rā came into being under the form of Kheperȧ from out of the primeval watery mass of Nu, and how by means of his soul, which lived therein with him, he made a place whereon to stand, and straightway created the gods Shu and Tefnut, from whom proceeded the other gods.

The worship of the beetle was, however, far older than that of Rā in Egypt, and it is pretty certain that the identification of Rā with the beetle-god is only another example of the means adopted by the priests, who grafted new religious opinions and beliefs upon old ones. The worship of the beetle, or at all events, the reverence which was paid to it, was spread over the whole country, and the ideas which were associated with it maintained their hold upon the dynastic Egyptians, and some of them appear to survive among the modern inhabitants of the Nile valley.

The particular beetle which the Egyptians introduced into their mythology belongs to the family called Scarabæiciae (Coprophagi), of which the Scarabaeus sacer is the type. These insects compose a very numerous group of dung-feeding Lamellicorns, of which, however, the majority live in tropical countries; they are usually black, but many are adorned with bright, metallic colours. They fly during the hottest hours of the day, and it was undoubtedly this peculiarity which caused the primitive Egyptians to associate them with the sun. Thus as far back as the VIth Dynasty the dead king Pepi is said

“to fly like a bird, and to alight like a beetle upon the empty throne in the boat of Rā.”

According to Latreille it was the species of a fine green colour (Ateuchus Aegyptiorum) which was first identified with the sun. The insect lays a vast numbers of eggs in a mass of dung, which it proceeds to push about with its legs until it gradually assumes the form of a ball, and then rolls it along to a hole which it has previously dug.

A ball of dung containing eggs varies in size from one to two inches in diameter, and in rolling it along the beetle stands almost upon its head, with its head turned away from the ball; in due course the larvae are hatched by the heat of the sun’s rays beating down into the hole wherein it has been placed by the beetle, and they feed upon the covering of dung which protected them. The mind of the primitive Egyptian associated the ball of the beetle containing potential germs of life with the ball of the sun, which seemed to be rolled across the sky daily, and which was the source of all life.

The beetle shows great perseverance in conveying the egg-laden balls of dung to the holes in which the larvae are to be hatched, and they frequently carry them over rough ground on the broad, flat surface of their heads, and seek, when unable singly to complete the work, the assistance of their fellows. It is this habit of the beetle which is represented in mythological scenes where we see the disk or ball of the sun on the head of the beetle,  . A curious view was held by the ancient writers Aelian, Porphyry, and Horapollo to the effect that beetles were all males (Κάνθαρος γὰς πᾶς ἄῤῥην), and that as there were no females among them, the males were, like the Sun-god Rā, self-produced.

. A curious view was held by the ancient writers Aelian, Porphyry, and Horapollo to the effect that beetles were all males (Κάνθαρος γὰς πᾶς ἄῤῥην), and that as there were no females among them, the males were, like the Sun-god Rā, self-produced.

This erroneous idea probably sprang up because the male and female scarabaeus are very much alike, and because both sexes appear to divide the care of the preservation of their offspring equally between them, but in any case, it is a very ancient one, for in the Egyptian story of the Creation the god, whose type and symbol was a beetle, not only produced himself, but also begot, conceived, and brought forth two deities, one male (Shu), and the other female (Tefnut).

The Father of the Gods

In the Egyptian texts Kheperȧ is called the “father of the gods,” , and in the Book of the Dead (xvii. 116) the deceased addresses him, saying, Hail, Kheperȧ in thy boat, the “double company of the gods is thy body,” but the form of the Sun-god with which he is most closely allied is that of Ḥeru-khuti, or Harmachis. In the Book of the Dead Kheperȧ plays a prominent part in connection with Osiris; he is called the “creator of the gods” (Ani, 1, 2); “Ḥeru-khuti-Temu-Ḥeru-Kheperȧ” (Qenna, 2, 15), and whatever forms he takes, or has taken, the deceased claims the right to take also. Moreover, the god Kheperȧ becomes in a manner a type of the dead body, that is to say, he represents matter containing a living germ which is about to pass from a state of inertness into one of active life.

, and in the Book of the Dead (xvii. 116) the deceased addresses him, saying, Hail, Kheperȧ in thy boat, the “double company of the gods is thy body,” but the form of the Sun-god with which he is most closely allied is that of Ḥeru-khuti, or Harmachis. In the Book of the Dead Kheperȧ plays a prominent part in connection with Osiris; he is called the “creator of the gods” (Ani, 1, 2); “Ḥeru-khuti-Temu-Ḥeru-Kheperȧ” (Qenna, 2, 15), and whatever forms he takes, or has taken, the deceased claims the right to take also. Moreover, the god Kheperȧ becomes in a manner a type of the dead body, that is to say, he represents matter containing a living germ which is about to pass from a state of inertness into one of active life.

, and in the Book of the Dead (xvii. 116) the deceased addresses him, saying, Hail, Kheperȧ in thy boat, the “double company of the gods is thy body,” but the form of the Sun-god with which he is most closely allied is that of Ḥeru-khuti, or Harmachis. In the Book of the Dead Kheperȧ plays a prominent part in connection with Osiris; he is called the “creator of the gods” (Ani, 1, 2); “Ḥeru-khuti-Temu-Ḥeru-Kheperȧ” (Qenna, 2, 15), and whatever forms he takes, or has taken, the deceased claims the right to take also. Moreover, the god Kheperȧ becomes in a manner a type of the dead body, that is to say, he represents matter containing a living germ which is about to pass from a state of inertness into one of active life.

, and in the Book of the Dead (xvii. 116) the deceased addresses him, saying, Hail, Kheperȧ in thy boat, the “double company of the gods is thy body,” but the form of the Sun-god with which he is most closely allied is that of Ḥeru-khuti, or Harmachis. In the Book of the Dead Kheperȧ plays a prominent part in connection with Osiris; he is called the “creator of the gods” (Ani, 1, 2); “Ḥeru-khuti-Temu-Ḥeru-Kheperȧ” (Qenna, 2, 15), and whatever forms he takes, or has taken, the deceased claims the right to take also. Moreover, the god Kheperȧ becomes in a manner a type of the dead body, that is to say, he represents matter containing a living germ which is about to pass from a state of inertness into one of active life.

As he was a living germ in the abyss of Nu, and made himself to emerge therefrom in the form of the rising sun, so the germ of the living soul, which existed in the dead body of man, and was to burst into a new life in a new world by means of the prayers recited during the performance of appropriate ceremonies, emerged from its old body in a new form either in the realm of Osiris or in the boat of Rā. This doctrine was symbolized by the germs of life rolled up in the egg-ball of the beetle, and the power which made those to become living creatures was that which made man’s spiritual body to come into being, and was personified in the god Kheperȧ.

Thus Kheperȧ symbolized the resurrection of the body, and it was this idea which was at the root of the Egyptian custom of wearing figures of the beetle, and of placing them in the tombs and on the bodies of the dead ; the myriads of scarabs which have been found in all parts of Egypt testify to the universality of this custom. As to its great antiquity there is no doubt whatsoever, for the scarab was associated with burial as far back as the period of the IVth Dynasty.

Thus in the Papyrus of Nu (Brit. Mus., No. 10,477, sheet 21) we are told in the Rubric that Chapter lxiv. of the Book of the Dead was found inscribed in letters of real lapis-lazuli inlaid in a block “of iron of the south” under the feet of the god (i.e., Thoth), during the reign of Men-kau-Rā (Mycerinus), by the prince Heru-ṭā-ṭā-f in the city of Khemennu.

Kheperȧ and the Heart

At the end of the second paragraph this Chapter is ordered to be recited by a man

“who is ceremonially clean and pure who hath not eaten the flesh of animals or fish, and who hath not had intercourse with women.”

The text continues,

“And behold, thou shalt make a scarab of green stone, with a rim of gold, and this shall be placed in the heart of a man, and it shall perform for him the ‘Opening of the Mouth.’ And thou shalt anoint it with ānti unguent, and thou shalt recite over it the following words of power.”

The “words of power” which follow this direction form Chapter xxx b. of the Book of the Dead, wherein the deceased addresses the scarab as

“my heart, my mother ; my heart, my mother ! My heart whereby I came into being.”

He then prays that it will not depart from him when he stands in the presence of the “guardian” of the Balance wherein his heart is to be weighed, and that none may come forward in the judgment to oppose him, or to give false or unfavourable evidence against him, or to “make his name to stink.” Curiously enough he calls the scarab “his double” (ha). Another Rubric makes the lxivth Chapter as old as the time of Ḥesepti (Semti), the fifth king of the 1st Dynasty, and the custom of burying green basalt scarabs inside or on the breasts of the dead may well be as old as his reign.

Be this as it may, scarabs were worn by the living as protective amulets, and as symbols of triumphant acquittal in the Judgment Hall of Osiris, and as emblems of the resurrection which was to be effected by the power of the god Kheperȧ whom they represented, and the words of power of Chapter xxx b made them to act the part of the ka or double for the dead on the day of the “weighing of words” before Osiris, and his officers, and his sovereign chiefs, and Thoth the scribe of the gods, and the two companies of the gods. If scarabs were placed under the coffin no fiend could harm it, and their presence in a tomb gave to it the protection of the “father of the gods.”

No comments:

Post a Comment